For the first time since the start of the full-scale invasion, Ukrainians took to the streets in mass protests in support of NABU and SAPO and against the government.

The trigger was an attempt by parliament to undermine the independence of the anti-corruption agencies NABU and SAPO – and, more importantly, the way in which MPs went about it.

They introduced amendments into a bill that had nothing to do with anti-corruption, voted on it in violation of parliamentary procedure, and by evening, the president had already signed it into law.

Ukrainian MP Yaroslav Zheleznyak admits the following Babel article as very good by on how the story of dismantling NABU and SAPO was constructed.

“It’s all accurate, Zheleznyak states. At first, they wanted and planned to do it more elegantly – through the Vlasenko/Buzhanskyi parliamentary committee. Then, when they realized that Mindich was about to receive a notice of suspicion, the President’s Office launched a turbo cringe campaign with bill 12414.

And then… now they’re trying to convince both ambassadors and journalists that it wasn’t them, but the SBU. Here’s a great example.

Starting from Wednesday, July 23, sources close to the President’s Office began telling Babel that it was actually the head of the SBU, Vasyl Maliuk, who initiated the amendments to the bill — that he personally approached MPs, and they, with the help of the ideologically driven Maksym Buzhanskyi and Hryhoriy Mamka, pushed the vote through. This version sounded illogical: Maliuk had neither the motivation nor the real influence over MPs, he couldn’t force the president to sign the law so quickly, and ultimately he wouldn’t benefit much from it.”

“For the second day in a row on the national marathon, they’ve been trying to convince everyone that it was all done independently by Servant of the People MPs,” – Zheleznyak summarizes.

Who initiated this fight — and what it looked like behind the scenes

Parliament

On Tuesday, July 22, members of the Servant of the People party were told by their faction leadership to be present in parliament without fail. The official reason announced was a vote on a parliamentary appeal to the U.S. Congress, urging stronger American leadership in supporting Ukraine.

However, some of the party’s MPs were in for a surprise. That morning, the Law Enforcement Committee had already passed amendments to draft law No. 12414 — a bill concerning missing persons. This was done without the participation of Committee Chair Serhiy Ionushas, Deputy Chair Andriy Osadchuk, or the head of the subcommittee on criminal law and author of the draft law, Oleksandr Bakumov.

A source in Servant of the People told Babel that the way the committee vote on the amendments was orchestrated was “ingenious” — in the worst sense of the word. The night before, one third of the Committee members quietly initiated a morning meeting, keeping it secret from the others. According to the source, Committee Chair Serhiy Ionushas had been “sent off” on a business trip, and the meeting was supposed to be chaired by his deputy, Osadchuk. But Osadchuk didn’t show up — and instead, the session was led by Maksym Pavliuk, a Servant of the People MP and deputy head of the Committee, who also happened to be the initiator of the bill on missing persons.

With no internal opposition present, the committee meeting went “smoothly.” Attending were the authors of the amendments and committee members — Servant of the People MPs Maksym Buzhanskyi, Vladyslav Borodin, Oleh Koliiev, and others. This is how a bill that originally had nothing to do with anti-corruption ended up containing provisions that weakened the powers of SAPO and NABU, stripped them of their exclusive right to investigate high-level corruption, and generally undermined the autonomy of all prosecutors. At the same time, the Prosecutor General was granted virtually unlimited powers — for example, to seize any case files and hand them over for “review” by other prosecutors, or even transfer them to other law enforcement bodies altogether.

Just a few hours later, the draft law was brought to the parliamentary floor. By that time, preparatory work with the MPs had already been done. In the Servant of the People faction’s group chat, members were urged to vote in favor and assured that the bill was extremely important and had already been coordinated with international partners. According to some MPs, they received phone calls the night before from faction leader Davyd Arakhamia and even from the head of the President’s Office, Andriy Yermak. There were also those who weren’t “worked on” — no pressure, no requests. These were the Servant of the People MPs who later refused to support the bill. They say it was clear the leadership already knew their stance and didn’t bother trying to sway them. Davyd Arakhamia was responsible for ensuring the vote passed, while MP Andriy Motovylovets was in charge of gathering the necessary votes.

Those who hadn’t seen the amendments beforehand had no idea what exactly they were voting for. According to parliamentary rules, MPs must be given at least 10 days to review a revised draft law before voting. Instead, the new text appeared on the Rada’s website just 15 minutes before the session — and in printed form only 5 minutes before. With 46 pages of complex legal language, there was no way to properly review it in that time.

Despite the violations, Parliament Speaker Ruslan Stefanchuk put the bill up for consideration. MPs from the Holos and European Solidarity parties tried to block it. European Solidarity MP Iryna Herashchenko managed to initiate a vote to suspend Stefanchuk from his duties for two plenary days for breaching parliamentary procedure. However, there weren’t enough votes. The Servant of the People MPs were told to “vote red” — and 132 obediently pressed the “against” buttons.

During the voting, Batkivshchyna MP Serhiy Vlasenko assured colleagues that the amendments simply restored the legislation to constitutional order. At 1:30 PM, the bill was approved by 263 MPs. To prevent the results from being overturned by a blocking motion, Servant of the People MP Maksym Buzhanskyi proposed to declare the bill “urgent.” This motion passed — and that same day Stefanchuk signed the bill, sent it to the Presidential Office on Bankova Street, and by evening the document bore the president’s signature.

“After the vote, many said that the Servant of the People MPs were broken over the knee, and that’s partly true — but it’s also true that some voted completely voluntarily because they hate the anti-corruption agencies. And there are reasons for that,” says a Servant of the People MP who voted against the bill. According to him, NABU has for years treated MPs with overt contempt. When detectives come to Temporary Investigative Committee meetings, their speeches and appeals are delivered in a way that makes every MP feel like they are worthless to them.

Another MP who also voted against the bill says that the “anti-anti-corruption vibe” in the Rada is partly fueled by cases against MPs themselves: in Servant of the People alone, 11 people have been suspected by NABU, but some of these cases have collapsed in court. For example, this was the case with Servant of the People MP Yuriy Kamelchuk — he spent years proving his innocence, and on March 16 the High Anti-Corruption Court acquitted him.

“Yuriy told how much time and resources he spent on those trials. And how many resources the state wasted as a result — stories like that affect people’s attitude toward the anti-corruption bodies,” the MP says.

Security Forces

The president’s team failed to anticipate the public’s reaction to the bill. When young people gathered in the squares on Tuesday evening with cardboard signs, the Presidential Office still didn’t grasp the scale of the protests. No one publicly commented on the situation. Instead, security officials were sent to speak with the media — Prosecutor General Ruslan Kravchenko and SBU Chief Vasyl Maliuk. Late on July 22, they held a press conference. Most of the time was spent talking about raids, Russian involvement, and moles inside NABU. Maliuk took center stage — speaking a lot and emotionally, frequently interrupting the prosecutor general and not letting him get a word in. Maliuk was clearly annoyed that the SBU, which fights Russian agents, executes operations like “Pavutyna” and undermines the Crimean Bridge, suddenly had to justify itself to journalists for exposing Russian agents within NABU.

Specifically, Maliuk was outraged that detective Ruslan Magamedrasulov, suspected of aiding the aggressor state, behaved arrogantly during an SBU raid, and earlier had initiated raids on National Guard Commander Oleksandr Pivnenko, which damaged the morale of his subordinates. “They [the detectives] should have been met at the entrance with guns — and two magazines left there,” Maliuk said emotionally.

Prosecutor General Kravchenko calmly assured journalists that he would not abuse the expanded powers and would not take away from NABU the case against Minister Oleksiy Chernyshov, which, according to many MPs and security officials, could have been one of the causes of the crisis between the president and the anti-corruption agencies.

Meanwhile, the number of protesters on the streets of various cities kept growing. In Kyiv alone, the evening protest, according to law enforcement estimates, gathered no fewer than 5,000 people. The next morning, Wednesday, a meeting took place at the president’s office with Prosecutor General Ruslan Kravchenko, NABU Director Semen Kryvonos, SAPO Head Oleksandr Klymenko, Interior Minister Ihor Klymenko, SBU Chief Vasyl Maliuk, DBR Head Oleksiy Sukhachov, and NAPC Head Viktor Pavlushchyk.

“The meeting was more about emotions than about the law,” says a Babel source familiar with the details. Prosecutor General Kravchenko mostly remained silent. Maliuk was, as usual, active. Zelenskyy and the heads of SAPO and NABU voiced mutual accusations. One of the main complaints from all the security officials to Semen Kryvonos and Oleksandr Klymenko was excessive PR by the anti-corruption agencies regarding their investigative actions.

“They loudly report even on searches, and after that people are already convinced that the person involved is a criminal. The fact that there might not even be a suspicion afterward doesn’t interest anyone — the person is already branded,” says the source, adding that no specific names or wishes regarding cases were mentioned during the conversation. There were also no hidden hints that NABU leaks parts of the materials to the media for PR purposes.

The official outcome of the meeting was an agreement to hold a new meeting — on July 28, the heads of the law enforcement agencies were to gather at the Prosecutor General’s office, develop proposals, and submit them to the president. Ultimately, everyone left the president with their own stance — the heads of NABU and SAPO wanted everything to be rolled back unconditionally, without compromises.

This position, in addition to the people on the streets, was reinforced by Western partners. Ambassadors from various countries began demanding meetings with government officials and the Prosecutor General. American senators reminded that support for Ukraine is tied to the effectiveness of the anti-corruption fight.

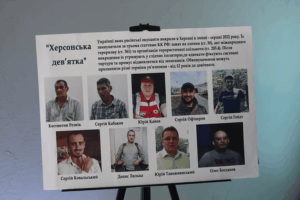

The deputies also faced a sharp backlash after the vote. The Ukrainian School of Political Studies expelled seven deputies from its institution. Following that, the Aspen Institute Kyiv banned nine parliamentarians from participating in the community’s events. Deputies in closed chats started asking many questions, expressing outrage that they were used blindly, and searching for those responsible.

At the same time, journalists were looking for the masterminds behind the complex scheme, while the President’s Office tried to “assign” them. Starting Wednesday, July 23, sources close to the President’s Office assured Babel that the amendments to the bill were initiated by the head of the Security Service of Ukraine, Vasyl Malyuk — he himself reached out to the deputies, who, through the ideologically driven efforts of Maksym Buzhanskyi and Hryhorii Mamka, carried out the vote. This version seemed illogical — Malyuk had no motives or significant influence over the deputies, couldn’t have forced the president to sign the law quickly, and ultimately would not have gained much from it. On the contrary, under the new law, the head of the SBU and his deputies remained the only heads of law enforcement agencies whom the head of the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office could still charge with suspicion.

Another so-called “ideologue” began to be named — Prosecutor General Ruslan Kravchenko, who, unlike Malyuk, had a motive but similarly lacked resources and claimed that he first saw the draft law only in the Telegram channel of MP Yaroslav Zheleznyak.

On the evening of Wednesday, July 23, the president promised to gather recommendations from the heads of law enforcement agencies and, based on them, submit a new bill that “will ensure the strength of the law enforcement system and will exclude any Russian influence or interference in the activities of law enforcement agencies.”

The President’s Draft Law

On the afternoon of July 24, Volodymyr Zelenskyy gathered journalists for a closed off-the-record meeting. The main question on everyone’s mind was how he planned to resolve the crisis. The journalists did not know that while they were waiting for the president without their phones, he was approving the text of a draft law which, according to him, would “protect the law enforcement system from the Russian trace and guarantee the independence of the SAPO (Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office) and NABU (National Anti-Corruption Bureau).”

At the off-the-record meeting, a visibly tired Zelenskyy, occasionally showing signs of irritation, tried to explain to journalists that the previous law had a mistake, at least in terms of communication. Now there was a new law, and he himself did not understand why the media was primarily interested in SAPO and NABU.

“Don’t you like that I often say the word ‘war’? It is simply there. And it is the greatest challenge,” the president said, adding: “I think that [the deputies] will vote for the presidential draft law.”

According to Babel’s information, the draft of the president’s bill was actually written by representatives of NABU and SAPO. The “moderator,” according to a source in the Office of the President, was Deputy Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov. They worked on the draft for nearly a full day, and the completed text was submitted to the President’s Office, specifically to the Deputy Head of the Office, Iryna Mudra.

“We are satisfied with the document — all our requests were taken into account. We were only waiting for its publication on the Rada’s website to check if the text had not been changed,” a NABU source told Babel.

The vote was scheduled for July 31. Some parliamentarians who previously supported bill 12414 have already publicly admitted their mistake, such as Tamila Tasheva from Holos. The situation within Servant of the People is complicated: deputies who were not protected by either the faction leadership or the President’s Office after the vote are demanding an “internal investigation” to clarify who was the mastermind behind the original bill and who is responsible for everything that happened. The situation is further complicated by the fact that some Servant of the People members have long talked about being ready to resign their mandates. These threats have recently intensified, but the faction does not take them seriously — a mandate cannot be simply relinquished; the decision must be approved by the Rada. Servant of the People is confident this will not happen.

Moreover, deputies who supported the controversial amendments now fear retaliation from SAP. Its head, Oleksandr Klymenko, told Suspilne in an interview that “we will thoroughly examine all these situations, events, statements, accusations, and claims raised against us. We will analyze everything down to the molecular level, recreate the timeline of events second by second, and provide an analysis.” Due to such statements, Davyd Arakhamia even told deputies in the faction chat that he is convincing the president and Western partners of the “need to guarantee the safety of every [deputy].”

P.S.

None of the deputies from various factions and law enforcement officials interviewed by Babel doubt that the scheme behind bill 12414 was conceived and executed by the President’s Office. Only there would there have been enough resources and influence to push such a bill through in one day, violating procedural rules, and secure the president’s signature that very evening.

The reasons for dissatisfaction with the anti-corruption agencies cited within the Office vary — from their insufficient effectiveness to the persecution of people close to the president, such as Minister Oleksiy Chernyshov.

Be that as it may, the authorities had a Plan A. On July 19, at the proposal of a Batkivshchyna deputy Serhiy Vlasenko, parliament established a Temporary Investigative Commission (TIC). It was tasked with investigating corruption in all law enforcement agencies. “In the end, the TIC was supposed to create something resembling bill 12414,” a source familiar with the Commission’s work told Babel.

The Temporary Investigative Commission (TIC) was headed by a staunch critic of the anti-corruption agencies, Serhiy Vlasenko, with Maksym Buzhanskyy as his deputy. The commission also included Opposition Platform — For Life (OPZZh) deputy Hryhoriy Mamka and “Servant of the People” deputy Maksym Pavliuk. The former later became the author of the scandalous amendments, while the latter pushed the amendments through the relevant parliamentary committee.

“Vlasenko had already drafted a rough version of the bill,” a Babel source says, “but something forced them to speed up and implement Plan B.”

Tags: Anti-Corruption EMPR.media nabu protests SAPO Ukraine Politics

![Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and French President Emmanuel Macron speaking during their meeting in Paris to align on air defense and diplomatic strategy ahead of Coalition talks. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/macron-300x156.png)