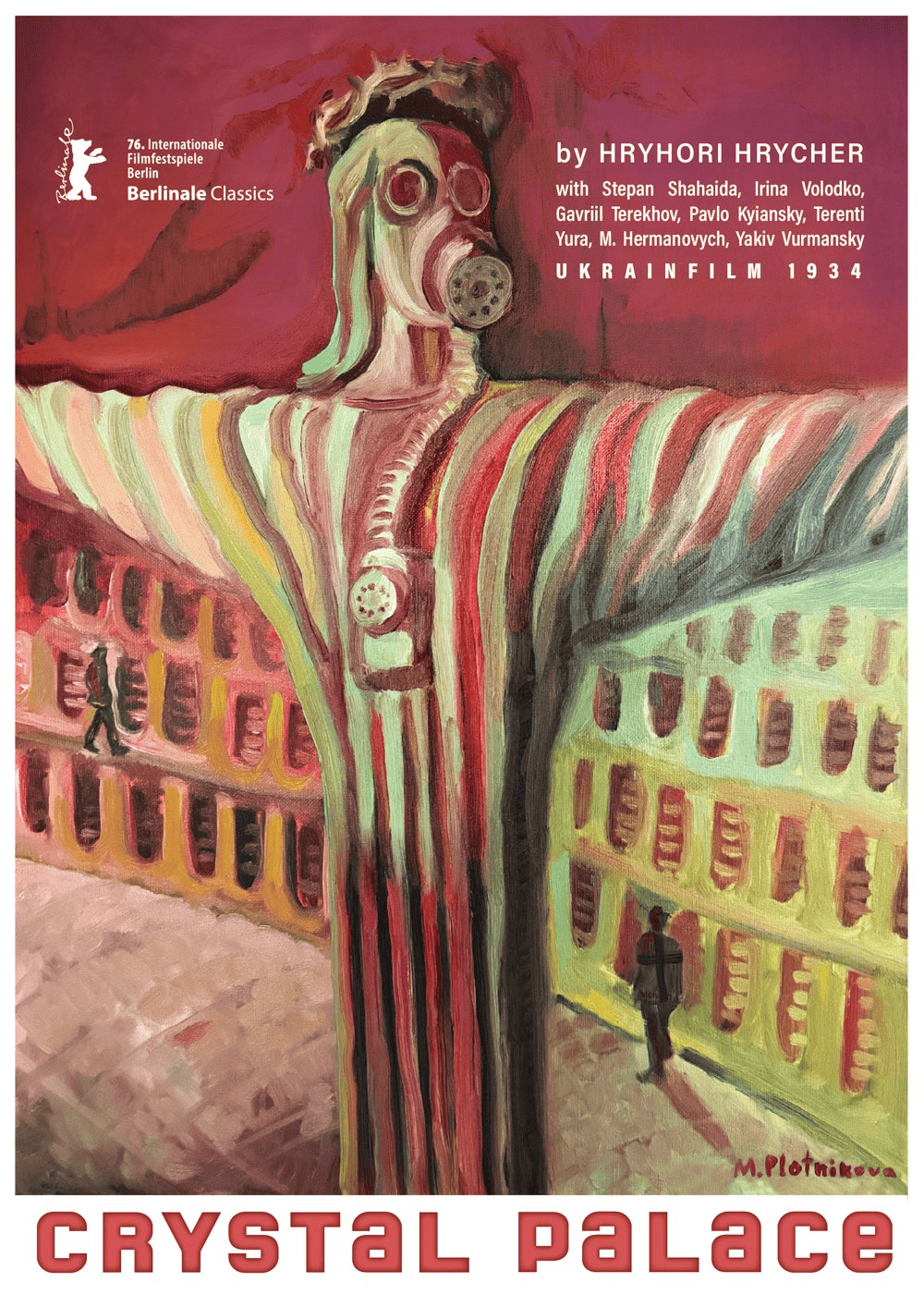

Berlinale 2026 screened the restored 1934 Ukrainian film The Crystal Palace, a pioneering sound film by Hryhoriy Hrycher with music by Borys Lyatoshynsky, highlighting 1930s culture.

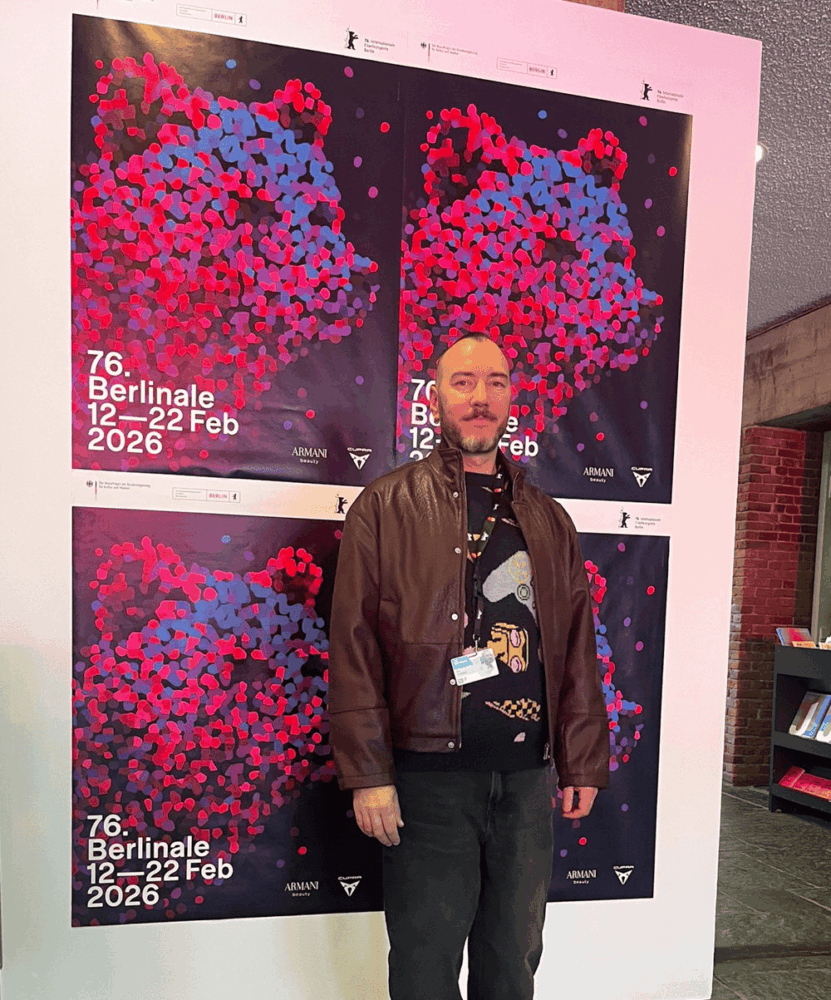

At the “Classics” program of Berlinale 2026, the Ukrainian film The Crystal Palace (1934) by Hryhoriy Hrycher was shown. This film, which had been banned, is not held in Ukrainian archives but has survived in the United States. It is one of the first sound films of socialist realism; the music was composed by Borys Lyatoshynsky. The festival presented a restored version, initiated by film historian Ivan Kozlenko. He believes that bringing this film back into circulation could change perceptions of 1930s Ukrainian Soviet cinema. This was reported by LB.ua.

The Berlinale special program “Classics” does not follow a specific theme; it is primarily aimed at presenting restored versions of films from different periods. This year, it features ten films from nine countries. They range from the avant-garde German film Secrets of a Soul (1926) by Georg Wilhelm Pabst, with new music by Yongbom Lee, where sound and light enhance the experiences of a psychoanalyst’s patient, to the Indian university telefilm In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1989), scripted by the writer Arundhati Roy, who also acted in it, and the Oscar-winning Leaving Las Vegas (1994) starring Nicolas Cage.

In Berlin, a city with a complex history of banned and “degenerate” art, the screening of The Crystal Palace — a 1934 film about an artist in conflict with authority — carries particular resonance. Of course, this authority is bourgeois and anti-communist.

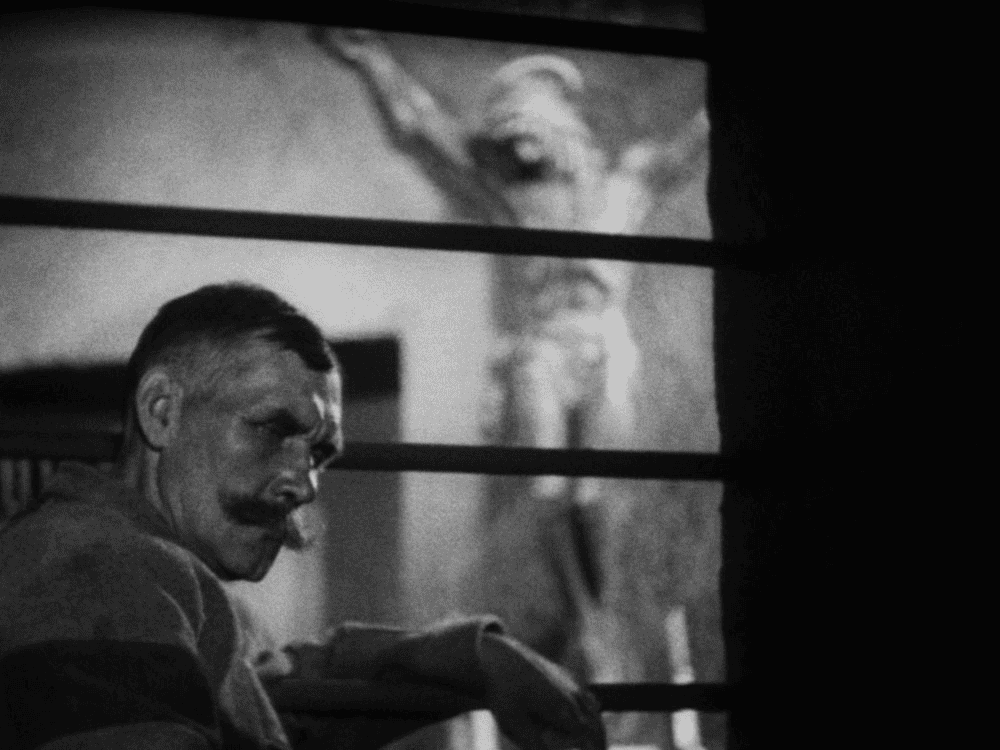

The plot follows sculptor Martyn Bruno, who receives a commission for a statue of Christ. His original interpretation would surprise even modern believers: at the unveiling, Christ appears wearing a gas mask, unable to breathe the suffocating atmosphere of society. The official in charge is shocked, to say the least. The exhibition itself resembles a precursor to the “degenerate art” shows of later years, even though the film was made earlier.

The artist faces trial, while his beloved longs for a better future and sings a song about a utopian “Crystal Palace,” accompanying herself on the piano. Here, the Crystal Palace alludes to The Fourth Dream of Vira Pavlivna from Chernyshevsky’s programmatic work, well known in 1930s Soviet culture: in glass palaces, a bright future blossoms. This image is also inspired by the famous London Crystal Palace of 1851 — a symbol of faith in progress, which was repeatedly destroyed over time. In the context of Berlinale, this utopian motif takes on a particularly ambiguous meaning.

The film was shot in Kyiv at the Dovzhenko Film Studio. It was created by a team shaping early 1930s Ukrainian cinema: director Hryhoriy Hrycher, screenwriter Leo Mur, composer Borys Lyatoshynsky, and cinematographer Yuriy Ekelchyk. The lead role was played by Iryna Volodko, already a recognizable film star at the time. This was not merely a commissioned work, but an attempt at developing a distinctive style.

“From 1930, when the persecution of the avant-garde as formalist practice began, until 1935, Ukraine experienced a very interesting period of experimentation — what I would call expressionist, an attempt to invent a style of its own variety of early socialist realism,” says Ivan Kozlenko. “The Crystal Palace changes the way we think about 1930s Ukrainian culture. It existed — and not merely as a victimized history. It represents a specific aesthetic, indirectly influenced by historical conditions: pressure, coercion, famine, repression, and so on. It was a kind of escapist project, where something was created over several years in a studio pavilion to avoid contact with reality.”

Immediately after its release, The Crystal Palace was banned. “But after the Nazis came to power in Germany, films on Western themes were taken off the shelves and temporarily screened again,” Kozlenko continues. “So for a short time it was shown, but then banned once more, this time permanently — because by 1935–1936, it no longer fit the newly established paradigm of socialist realism.”

A copy of the film eventually ended up at Amherst College (USA), donated by an anonymous benefactor. It is believed that materials also exist in the Russian Gosfilmofond, but access to them is currently impossible.

It was during his fellowship at this college that Ivan Kozlenko initiated the restoration — to bring the film back into both Ukrainian and international research contexts. Without a high-quality restored copy, this would not be possible.

“Some people send drones to Ukraine, and I do what I do best,” says Łukasz Ceranka, co-founder of the Polish company FixaFilm, which took on the restoration free of charge. The company had previously worked with the Dovzhenko Center, preparing Serhiy Paradzhanov’s films for the Bologna Festival of Archival Cinema.

The Crystal Palace — one of the first domestic sound films — has survived in its Ukrainian-language version, with music by Borys Lyatoshynsky. During the restoration, titles were created based on typographic designs of the 1930s.

In a program that works with restored cinematic pasts from various countries, the appearance of a 1934 Ukrainian film resonates as more than just an archival event. It is a reminder that cultural history is also a field of struggle and reclamation. From a 1930s studio pavilion, The Crystal Palace is transported into a Berlin screening hall in 2026. Those who understand Ukrainian smile at the slightly mechanical delivery of the actors’ lines, while everyone laughs together at the jokes and everyday situations. The film is entirely accessible within European culture, even across a century.