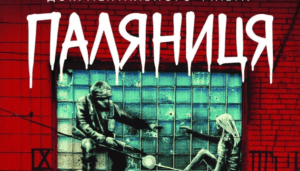

Former POW and journalist Dmytro Khylyuk recounts his captivity, harsh conditions, survival, limited state support after release, Europe’s inaction, and his efforts to rebuild life and home.

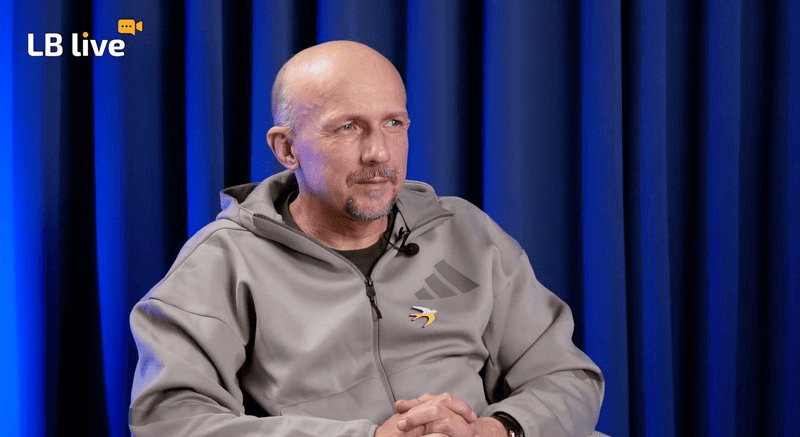

Russians kidnapped UNIAN journalist Dmytro Khylyuk on March 3, 2022, in the village of Kozarovychi. He passed through filtration camps in the Kyiv region, Belarus, and the Bryansk region. He spent the longest time in Pakino, Russia. He was held in captivity for over three years, enduring cold, hunger, and psychological pressure. On August 24, 2025, he was finally returned home as part of a large prisoner exchange.

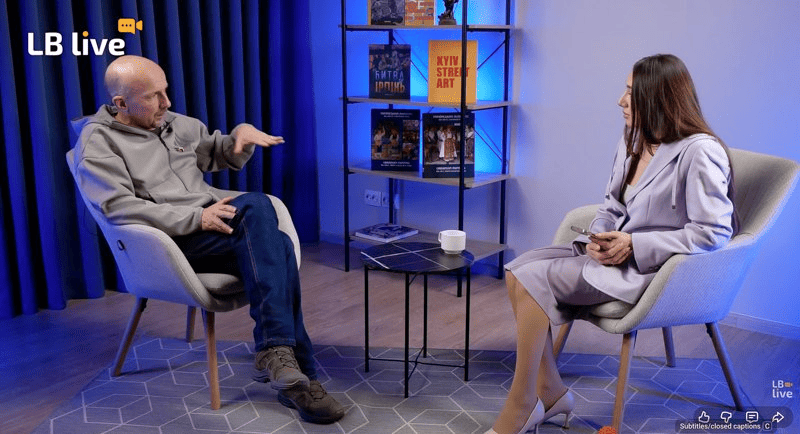

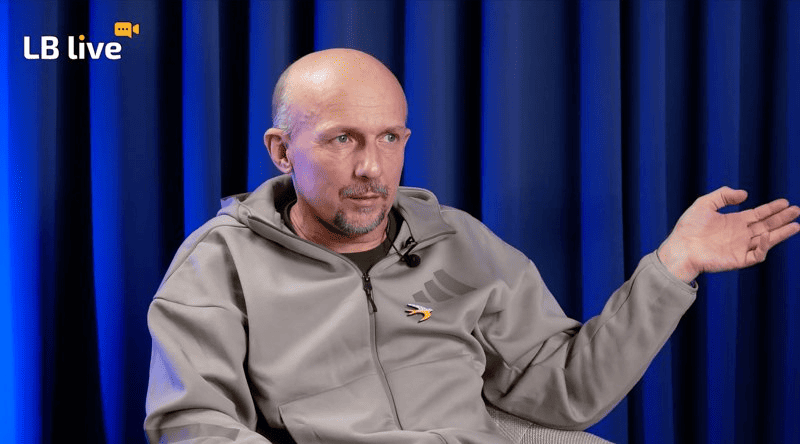

In this interview for LB Live, Khylyuk talks about the horrific conditions of his captivity, survival strategies, hunger, and daily life in prison. He also discusses state assistance, rehabilitation after release, and what the war looks like both from prison and upon returning to civilian life.

“Russians explained their hatred of Ukrainians simply: ‘And who gave you the right to live so well?’”

Anzhelika Syzonenko: If we set aside the beatings and hunger that they inflicted everywhere, and focus just on your personal feelings: where was it the worst for you, and why?

Dmytro Khylyuk: That was Novozybkov, Bryansk region. Primarily because of the conditions. It was an emergency building with two wings — one dating back to the Tsarist era, with vaulted ceilings like they used to build. Some cells had no windows at all. In some cells, the toilets didn’t work due to rotten sewage. Overall, the conditions were terrible. But the main thing was the cold.

The freezing cold lasted from early September until around the 20th of May. There was heating, radiators were there, but as soon as the temperature rose slightly, they immediately reduced the heat supply. In winter, we literally just stood with our backs to the radiator, hands on it, and didn’t move. Because if you stepped back even twenty centimeters, you’d start freezing.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: How many of you were in the cell?

Dmytro Khylyuk: In Novozybkov, I spent almost all the time with a guy from Irpin. He’s a civilian. Unfortunately, he’s still in captivity — now in Pakino. The three of them were captured: him and two friends. They were hiding in basements because Irpin was being heavily bombed. He went out to walk his dog — something made a loud noise, the dog got scared and ran into the street. He went after it, and his friends went after him. All three of them were caught along with the dog. What happened to the dog is unknown. They brought them through Hostomel to us. I was with this man almost the entire time — in Novozybkov and later in Pakino. In Pakino, the cell was already large — up to 15 people.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: Was there a difference in how the Russians treated civilians, journalists, and military personnel?

Dmytro Khylyuk: No. The only difference was in age and physical condition. They especially tormented young men aged 20–25. Even after 30, it was “less interesting.” If someone was young and physically strong, they openly hated them. Probably out of fear. Even though everyone stayed quiet like mice and just wanted to survive.

They were particularly harsh with military personnel in combat specialties: mortarmen, scouts, and officers.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: As a journalist, I left Irpin on February 25 because I understood they were already approaching, and I could either be raped, killed, or definitely taken captive. As a journalist, did you ever have such thoughts?

Dmytro Khylyuk: For me, those thoughts came late — as they say, hindsight is 20/20. The first three days, the Russians behaved more or less calmly: they stayed on the shore of Kyiv Sea near the village and hardly entered. They went through houses asking for food, but they didn’t come to us. But from February 28, when the “blitzkrieg” failed and our forces started hitting them, they entered the village and began “sweeps”: looting, pillaging, taking phones.

That’s when I realized there would be no distinction between military and civilians. I had previously thought: war — it might strike by accident. But that they would deliberately loot and abduct — it was unimaginable.

The first time they came, supposedly for a search: they forced us, my parents and me, onto the street and checked for tattoos. They didn’t find any spies, but my mechanical watch disappeared. They also took my parents’ basic phones and a flashlight.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: I’ve heard different stories about the guards, mostly about their cruelty. But sometimes they said there were some more humane ones.

Dmytro Khylyuk: We had one like that; his name was, I think, Roma. He didn’t guard often, but in the evenings you could talk to him. On January 30, 2023, he told me that Zelenskyy doesn’t want to stop the war on Putin’s terms. Later, he even gave me two candies — secretly, asking me not to leave the wrappers. Because any humane behavior there is punished.

The other guards explained their hatred simply: “And who gave you the right to live so well?” The Ukrainian language or accent would make them furious. There was no talk of “brotherly peoples” — only the logic of conquest: “We came — now this is ours.”

“Three years I didn’t know whether my father was alive”

Anzhelika Syzonenko: Was there a complete information vacuum for you?

Dmytro Khylyuk: At first, we still had old Soviet televisions. They were carried from cell to cell — a couple of days in one, then another. We were forced to watch only their news — about the “valiant Russian troops” and the “liberation” of Ukrainian territories. There was nothing else; the antenna reception was poor.

But when the Russians started taking hits from our forces in September 2022, the televisions were taken away for good. And that was it — a complete information vacuum.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: I know you also had a personal story involving your father. You were both taken captive, and you didn’t know whether he had been released. You only found out two years later, when a letter arrived.

Dmytro Khylyuk: It took two years for that letter to reach me. And I found out that he was alive after three years. We were taken together, and we were together in Kozarovychi and Dymer. Then we were taken to Hostomel, but when they read out the names, his name wasn’t called. I didn’t know what had happened to him.

It seems that in April this year, Ruslan Panchenko was in a neighboring cell — he saw my father being released. That’s how I indirectly learned that my father had been freed. Later, a letter arrived, with a photo of my parents taken in the summer of 2023.

For three years, I wasn’t sure at all that he was alive. And that was the hardest part — not the hunger, not the beatings, but the absolute uncertainty. Not knowing what was happening at home, with the country, with loved ones — that was psychologically more frightening than anything else.

“Hunger turned people into animals: I even tried eating toothpaste”

Anzhelika Syzonenko: About hunger… You’ve often said that they fed you something like soup — not really soup, just water. You couldn’t get full at all.

Dmytro Khylyuk: It was very hard in the first prison… Sometimes I would look at a bar of soap and it seemed like ice cream. I tried eating toothpaste. Well, not really eating it, but just to trick my taste receptors. People diluted the thin porridge with water so it would last longer.

Hunger gnawed at you constantly. It was especially hard for those who were big or weighed over 100 kilograms — they needed more calories, but everyone was given the same tiny amount. I know people who weighed 120 kilos in civilian life and only 60 in captivity. They lost half their body weight.

Some tried to be clever: they traded food with others, stretched it over several days, postponed the moment of eating. Some tricked hunger by biting a sandwich with the tip of a spoon or taking very small pieces, just to feel like they were eating for longer.

It was also a psychological ordeal: hunger made people angrier, more aggressive, almost animal-like. Many lost their human dignity — they licked other people’s plates so nothing would go to waste. It was both ridiculous and terrifying at the same time.

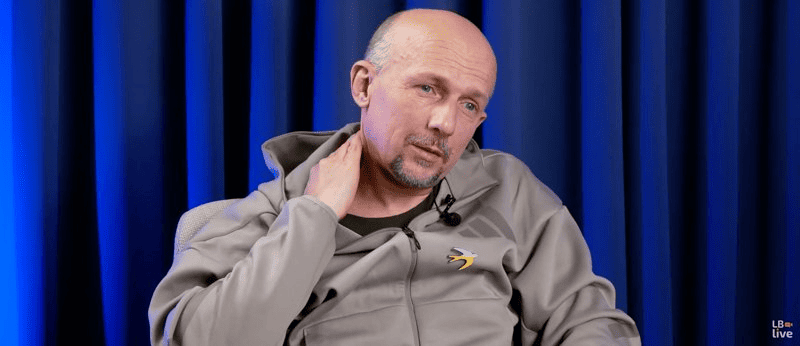

Anzhelika Syzonenko: I also know that in captivity people usually choose between two behavioral strategies: either submission — some even try to form a kind of conditional “friendship” with the guards, showing them a better attitude just to survive. Or resisting the system — constantly getting into arguments with them. Which approach did you choose for yourself?

Dmytro Khylyuk: I chose what I’d call quiet sabotage. Because going head-on there makes no sense. They’ll simply cripple you, smash your kidneys. And a person can die from beatings.

Yes, there really were two modes of behavior. One is what I call a kind of victim complex. That’s when a person accepts that they’re in prison, that they’re somehow guilty, and adopts these prison rules: “if the officer allows it,” “the officer said,” and so on.

And when they punished us because someone was standing wrong, or someone was sitting instead of walking, it was your own people who started pressuring you: “Why aren’t you following their instructions?” I told the guys that instead of uniting in submission, we should unite in resistance. That doesn’t mean walking up and saying, “Go to hell, guard.” No. But doing it more cleverly, more softly: “Yes, yes, sure, we’ll do it” — and then doing your own thing.

But there were people who got on those prison rails: they accepted themselves psychologically as victims, as some kind of criminals. And behaved accordingly. It was very unpleasant to watch such people: they were essentially demoralized, and it was simply painful to observe their behavior.

“Until the summer of 2024, we were beaten almost every day — kicked, beaten with batons on the ribs and legs.”

Anzhelika Syzonenko: In one interview, you said that after 2024 the beatings practically stopped. I might be mixing up the date — correct me if I’m wrong.

Dmytro Khylyuk: Yes, that was in early June 2024. Some kind of scandal happened there — possibly even an international one, though not public. They returned a group of Chornobyl workers from Pakino, and they were in terrible condition. One guy was basically a skeleton — extremely thin, visually frightening.

After that, those who had been in the cell with him were forced to write statements saying that he supposedly refused to eat himself, not that he was poorly fed. People, of course, wrote: “Yes, I refused to eat.”

On June 8, we were weighed for the first time. And after that, sometime around the first or second of the month, they started pouring a bit more oil into that slop — at least some vegetable fat appeared. Before that, it was pure hell.

The same with the beatings: one of the guards let it slip, saying, “You should be thankful they banned us from putting pressure on you.” So something definitely happened — that’s why they eased off a bit both with the food and with physical violence.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: And before that, were the beatings daily?

Dmytro Khylyuk: It depended on the shift. There was a general instruction — to keep “pressuring the Ukrainians” so they wouldn’t relax. But everyone did it in their own way. Some forbade us from sitting on the bed or a chair. Others, during inspections, made us waddle down the corridor like seals. If someone didn’t keep up, they could be kicked or hit.

There were people there aged from 22 to 62. They beat us in ways that wouldn’t leave bruises: on the ribs, the legs, with batons. It wasn’t like in the movies — they didn’t throw bloodied people back into the cells. But it happened. Especially before the summer of 2024. Especially during inspections and when the “beasts” came on duty.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: The former mayor of Kherson, Volodymyr Mykolaienko, was also held in Pakino — he told me in an interview that his ribs were broken twice.

Dmytro Khylyuk: But he was in a different block. Different guards, different “rules.” In our block, after June 2024, they stopped beating us openly. Though there was no logic to it. For example, shortly before my release, the entire floor was simply overfed with bread. They gave as much as you wanted: one loaf, two loaves — those old Soviet bricks. For us, it was happiness. That went on for about three weeks in July.

And when, after my release, I asked Mykolaienko whether they were given bread during that same period, he said no. The same prison, just a different block, a hundred meters away.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: As the exchange got closer, did you feel that it would happen and that you would be taken?

Dmytro Khylyuk: I didn’t feel it, but I hoped. Every time, we hoped the exchange might be larger. We pinned our hopes on state holidays: Independence Day, Flag Day, Pokrova. And also religious holidays: Easter, Christmas, as well as the secular New Year.

We also hoped around their holidays: Russia Day, May 9 — maybe they would want to bring their people back, and accordingly us as well. We had the same hopes around August 24 — that someone would be taken, that someone would get lucky, at least one or two people. And that’s basically how it turned out.

From our prison, essentially only Mykolaienko and I were taken. There were around 260 people there, and when they took me away, everyone else stayed behind.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: And so they were taking you somewhere — you already understood it was most likely for an exchange, but there were no guarantees. When did you realize you were really home?

Dmytro Khylyuk: The story was interesting. I realized we were being taken home on the 21st or 22nd. On the morning of the 21st, they pulled me out of the cell: “Out with your things.” I took my “treasures” — a mattress, a mug, a spoon — and they led me to the block from which people are sent out.

They put me in what’s called a transfer cell. There I met Mykolaienko and two other people. That same day, they took away our prison uniforms and issued used “pixel” camouflage — Ukrainian Armed Forces uniforms — and worn-out shoes. Then they forced us to record a video with a text about “good treatment” and to write a short biography.

After that, they returned us to our cells. From the 21st until the evening, we sat on our bags, and on the 22nd they scattered us back into different cells. It was a terrible disappointment, despair. I thought: that’s it, the exchange started and then collapsed.

And on the 23rd — again, “out.” When I went down to the first floor, they said: “Drop the mattress, leave your things.” They changed us into military uniforms — this time only me and Mykolaienko. They blindfolded us with medical bandages and tape. An assistant from the administration gave evasive answers when I asked whether we were going home, and that’s when I understood that yes, we were.

They took us in a prison van to a military airfield near Moscow. We spent the night in a cold hangar among our fellow prisoners. In the morning, they put us on a transport plane. We landed in Belarus, in Gomel, and from there were taken by bus to the border.

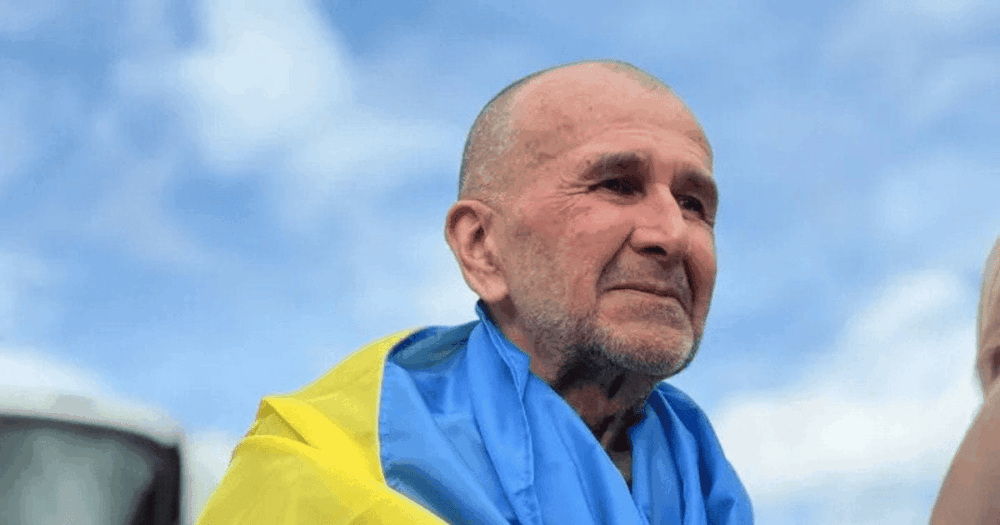

Of course, the emotions are impossible to put into words. For the first time in three and a half years, I saw civilian buses and ordinary people.

On the plane, while there were no outsiders around, they behaved roughly — swearing, shoving. But after landing, they gave the command: “Remove the blindfolds, untie your hands,” and their behavior became more proper. When I saw the bus, I realized: we were going home.

“The state leaves civilians with almost no support after captivity”

Anzhelika Syzonenko: What did the state provide for you as a civilian after returning from captivity?

Dmytro Khylyuk: Essentially, all that was provided was a one-time compensation: 100,000 hryvnias for the mere fact of captivity, regardless of whether you were held for a month, a year, or several years. And another 100,000 for each year of captivity. The first 200,000 were arranged by my parents while I was still in captivity — lawyers helped them. And for 2025, I received another 200,000: 100,000 as a one-time payment and 100,000 for the year.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: I know that military personnel are immediately offered examinations and rehabilitation — there’s a serious program. For civilians, the situation is much worse. Tell me about it.

Dmytro Khylyuk: Everything for us is handled manually. We were immediately taken to a regional hospital. They had a certain protocol. As I understand it, its purpose was not so much treatment as ruling out serious diseases that can be contracted in prison: tuberculosis, hepatitis, HIV.

I also complained about a rapid heartbeat and thought it might be related to the thyroid — they checked that as well.

As for dental care — only tooth extractions. Prosthetics aren’t even discussed. And dental problems affect 100% of those who return from captivity.

We stayed there for four weeks, then were discharged. Each of us was given a medical summary: what was done, what was found, and how to treat it. So there was some minimal package of services. You can’t say we were completely ignored.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: But there was no full medical examination? The stomach, for example? It’s obvious there must be problems — you were starving.

Dmytro Khylyuk: If a person complained about something, they might look into it. I complained about my thyroid — they checked it and even did a biopsy. But there’s a man, Volodymyr from Kyiv. He was diagnosed with a serious heart defect. Now he’s being treated in private clinics for a lot of money and is asking acquaintances for help. Before captivity, he was an athlete, a wrestler, a very physically strong person. He developed the condition there, in prison.

As for rehabilitation, that’s a story in itself. At the hospital they said there were supposedly some sanatoriums in the Kyiv region, maybe in Pushcha-Vodytsia. But then — silence, no specifics at all. And only a month ago I accidentally found out from a fellow former captive — he’s now with the NGO “Civilians in Captivity.” He attended a roundtable where the director of a sanatorium was present. She asked: “Why aren’t you coming to us?” — “How were we supposed to know?” — “Didn’t they tell you at the hospital?” — “No.”

That’s how it works: the right hand doesn’t know what the left is doing. Everything is handled manually. There was another case, too: Vereshchuk came to the hospital, gave her phone number and said, “If something isn’t being processed — call me.” They called — someone got reprimanded, the wheel turned a little, and then it rusted again and stopped. There’s no system, no algorithm like there is for the military.

“A social worker is needed to accompany people after captivity”

Anzhelika Syzonenko: How would you like this to work?

Dmytro Khylyuk: There should be someone — a coordinator, a fixer. Because when you come out of captivity, you’re lost. It’s like a cat that has lived its whole life in a stairwell and is taken out onto the grass for the first time.

At first, they help: they bring things, clothes, help restore documents. But then there’s an avalanche of information and problems, and you get lost in it.

What’s needed is a social worker who would oversee several people — five, ten, twenty. Someone who literally guides you by the hand: where to go for healthcare, for documents, for legal aid. At the very least, a checklist — where to turn and who to call if you’re denied something you’re entitled to.

Most people don’t even know what options exist. Programs may exist somewhere, but no one talks about them.

For example, there is a Coordination Center that works with the Prosecutor General’s Office and helps former captives — both civilians and military personnel. I found out about it… from an acquaintance who lives in London. Through several intermediaries. And then someone from the Center called me themselves.

Not everyone has a place to live. Especially IDPs. That same Kostya is now renting an apartment in Kyiv — a charity helped him for a few months. And then what — no one knows. He was offered a dormitory, but he said: “I spent seven years in prison. I want to be alone. In my own room.” He refused.

There’s a guy from Melitopol — Mark Kaliush. He needs guardianship because of his psychological condition. He’s still living in a rehabilitation center near Kyiv because the issues of guardianship and housing haven’t been resolved. His relatives are in occupied Crimea.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: And what about psychological support? All of us who have lived through four years of war already need a psychologist. Those who went through captivity — even more so.

Dmytro Khylyuk: I’m not working with a psychologist. I didn’t see one at the regional hospital. They said there was one, that they visited someone. But it was more formal than real.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: How is that possible — people return from captivity and no one even talks to them? And do you yourself feel any triggers? Are you sleeping okay, recovering?

Dmytro Khylyuk: I have this feeling that I’m rushing to live. Sleep feels like a waste of time. I wake up in the morning — a pile of things to do. I go to bed at two in the morning. And it just keeps going in a loop.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: And everyone keeps pulling you in different directions. You give interviews, travel abroad, speak out about what the Russians do to captives. Tell us about your trips abroad. You were in Brussels, in Warsaw?

Dmytro Khylyuk: Yes, I was in Brussels, Warsaw, and Strasbourg. Strasbourg — that was late September to early October. It coincided with the 30th anniversary of Ukraine’s membership in the PACE.

In the Palace of Europe, in the corridors of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, there was an exhibition about imprisoned journalists. A separate stand focused on journalists killed by Russians, and another stand about journalists who had been held captive. Among us, the released ones, I think there were four of us — we were marked in green.

There were speeches at the meetings of the relevant parliamentary committee, several meetings, including with the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights. Separately, there was a meeting with the PACE president — him and us, former captives.

In Warsaw, there was an OSCE conference. There was also a Ukrainian panel, organized by the UK ambassador to the OSCE.

I spoke about how you cannot trust the Russian narrative. About their “great culture,” “Tolstoy-like,” as we ironically say. In reality, behind that facade is a brutal horde that kills, maims, bombs cities, deliberately targets civilians, and shoots at buses.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: Did you feel support? Was there a sense of solidarity? Were you trying to convey that the return of people from captivity requires more active action?

Dmytro Khylyuk: They listen. When you tell them, you can see from their faces that it affects them. But how much those emotions translate into political decisions — who knows.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: We see it in the news: when there’s a large-scale attack in Ukraine with many casualties, they start to react a little. Images of dead people on destroyed streets shock them. But when two or five die, it barely affects them.

Dmytro Khylyuk: They’re inert. They’ve been living in their comfortable bubble for 80 years since World War II. We push them with a stick, but they don’t want to act. They pull the warm blanket over themselves and hope the draft won’t reach them. They think, “Somehow it will sort itself out.” Something needs to be done — but they’re scared and unwilling.

Recently, the Prime Minister of Belgium said, “We are not at war with Russia.” Well, fine, you’re not at war. But Russia will be at war with you. And Russia threatens: if the frozen funds in Belgium go to reparations for Ukraine, Europe “will have no peace for hundreds of years.”

It looks like the behavior of someone who’s been intimidated. And this is NATO’s capital — it even says in their airport: Welcome to NATO. Yet there’s this demonstrative fear.

“A country should live in a full state of war — everyone must act systematically, not just volunteers”

Anzhelika Syzonenko: Ukraine has changed a lot during almost four years of full-scale war. What surprised you most after returning?

Dmytro Khylyuk: In a positive sense, I was surprised that despite the war, people are living. Cities and even villages are being rebuilt. I came to my village — there are parcel lockers, a major overhaul of the water supply system was done. I was convinced that during the war there would be no major expenditures — neither budgetary nor commercial. But no — they’re building. On Pochaina, an office center has appeared that wasn’t there a few years ago.

And that’s good. You can’t live all the time thinking, “I’m doing nothing because something will hit tomorrow.” If it comes, it comes. If it doesn’t, life still goes on.

What was unpleasantly surprising was something else: even in Kyiv, despite regular shelling and casualties, the country is not fully living in a state of war. It’s not the kind of societal mobilization we saw, for example, in Britain in the 1940s, when the whole state was on a war footing.

We don’t have that. Here, roughly, “half the world jumps, half the world cries”: people die in one place, while others just move on, step over it, and go. And that’s a problem.

This is a question for the authorities. In my opinion, the country should live in a full state of war. High school students should learn to make drones, weave nets, help systemically — not just volunteers acting on their own initiative, but the entire state.

Right now, the war for many people exists somewhere on the television. And it reminds me of a dystopia: life goes on above, but at night someone is taken away. Everyone knows more will be taken, yet they continue living as if nothing will happen.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: And how do you perceive political scandals — the same Mindichgate, corruption in the energy sector, raises for MPs?

Dmytro Khylyuk: It’s disgusting. Simply repulsive. Because if something goes wrong — they all have a safe rear. From the top officials of the state to people with money and power. They can leave — by car, train, however they want. Everything is prepared: passports, houses, accounts. Most people don’t have that. And what angers me the most is that they steal knowing that even if it worsens the country’s situation, nothing will happen to them. In peacetime, people would already be standing outside the Presidential Office. But now you understand: any protest helps the enemy. And corrupt people take advantage of this. You stay silent — and they keep stealing.

Anzhelika Syzonenko: What are your personal plans and desires now?

Dmytro Khylyuk: To restore my house — the occupiers broke and destroyed a lot there. And then just to rest. Really rest. Somewhere without a phone, calls, or messages.

Tags: captivity and hunger Dmytro Khylyuk journalist interview prisoner exchange russia ukraine war war human stories

![Kyrylo Marsak in Olympic figure skating gear smiling on the ice at Milan-Cortina 2026, capturing pride, viral hopak atmosphere, and Ukraine energy. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/kyrylo-480x270.png)

![Volodymyr Kudrytskyi discusses energy missteps, shelters, and leadership decisions in Ukraine’s energy sector in a cold office interview.:contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/nardep-1-480x270.png)