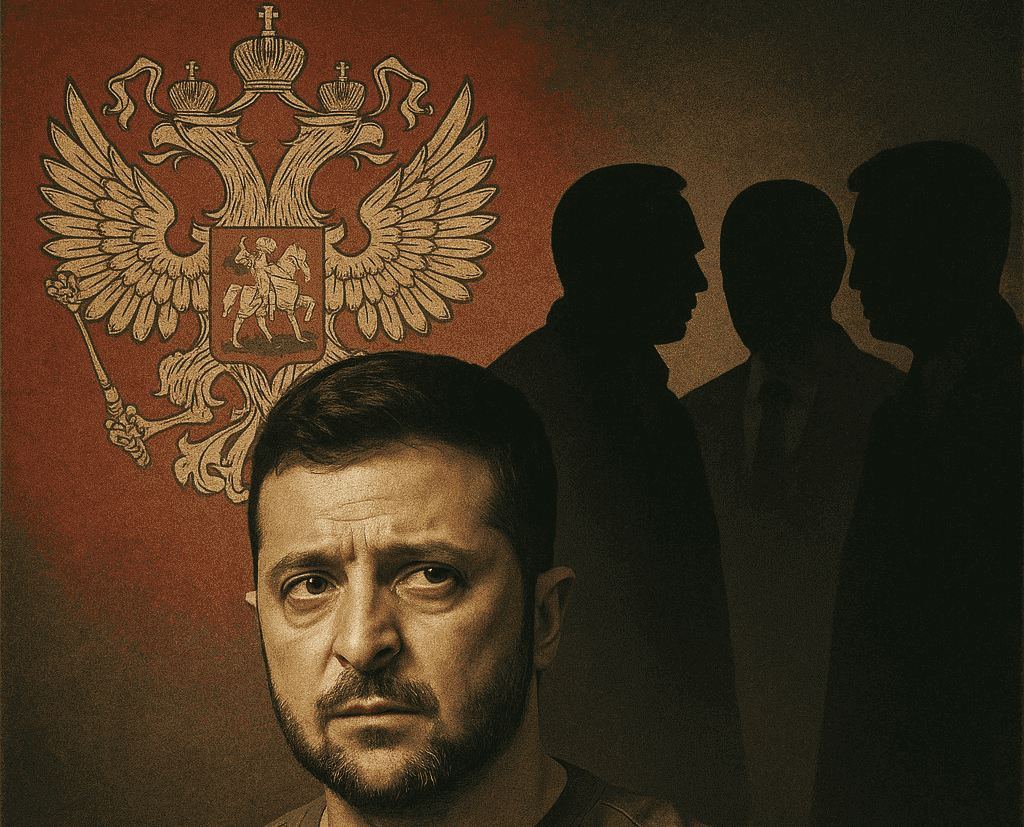

Growing public concern surrounds the close circle of President Zelenskyy’s top aides – including figures such as Andriy Yermak, Oleh Tatarov, Rostyslav Shurma, and others – amid ongoing debates about transparency, influence, and national security.

While officials continue to project confidence, questions about accountability and potential risks to Ukraine’s political stability remain pressing.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, speculation has increasingly arisen that the highest levels of Ukraine’s leadership may have been the target of a successful multi-layered operation by Russian intelligence services.

In particular, the circle surrounding President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is under suspicion – his chief of staff Andriy Yermak, his deputies Oleg Tatarov and (until recently) Rostyslav Shurma, the president’s close friends and business partners (Tymur Mindich, the Shefir brothers), as well as influential government figures like Davyd Arakhamia, Mykhailo Podoliak, and even some military leaders such as General Oleksandr Syrskyy.

All of these individuals have biographical or business ties to Russia – indirect, but significant indicators that can justify distrust.

Can these facts alone support the claim that Zelenskyy’s team is a “successful project of Russian intelligence”?

This article examines each aspect in detail: the known evidence and connections, how they fit into the broader picture of Russian influence, and whether this is sufficient to draw such radical conclusions.

Vladyslav Smirnov investigates.

Zelenskyy’s circle: ties to Russia before and after 2014

Around President Zelenskyy, a team has gathered, much of which had little prior experience in politics. However, almost every one of these new faces has a background connected to Russia or pro-Russian circles. Before being elected president, Zelenskyy himself was a well-known showman who built his career and business not only in Ukraine but also actively worked in the Russian media market. His colleagues from the “Kvartal-95” studio and personal friends also conducted business projects in Russia for a long time. Some current high-ranking officials in his team come from the former ruling elite that closely cooperated with Moscow (the Viktor Yanukovych regime) or have relatives in Russia.

Below we examine key individuals and facts:

Andriy Yermak: family ties to the GRU and Russian business partner

Andriy Yermak’s father, Borys Yermak, turned out to be a retired officer of the Russian Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU). Investigative journalists revealed this information, noting that Borys Yermak was also the director of his son’s company and a business partner of Russian citizen Rakhim Emanuilov.

Emanuilov is not just a Russian entrepreneur but an advisor to the Chairman of the Federation Council (the upper chamber of the Russian parliament, part of whose members are personally appointed by Vladimir Putin). Moreover, on social media, Yermak’s father openly calls this Russian a like-minded friend, sending warm greetings and expressing “respect for your position and today’s events.” Such a level of personal relationship is hardly compatible with a genuinely patriotic stance: the Yermak family appears closely connected to Russian political circles.

Before entering public service, Andriy Yermak built his career in film production. He worked as a producer, engaged in legal activities in the media sphere, and collaborated with Russian film companies. Even after 2014, his business ties with Russia continued: the aforementioned Rakhim Emanuilov was a co-owner of the “European Partnership Media Group” established by Yermak. In other words, a close Kremlin associate held a stake in the company of the future chief of the Presidential Office, raising serious questions about potential influence.

Notably, despite these facts, President Zelenskyy fully trusts Yermak and assigns him the most delicate responsibilities. Since 2020, Yermak has headed the Presidential Office and oversees negotiations concerning Donbas. The level of trust between them is so high that “Yermak’s thoughts and actions instantly resonate with Zelenskyy,” according to one counterintelligence officer. Critics point out that Zelenskyy appointed Yermak despite being aware of his biography – his Russian mother, his father the intelligence officer, and his business with a Russian citizen. This seems incredible, but it is possible the president did not give it much weight due to personal friendship and loyalty. I personally do not think so.

The most high-profile scandal involving Yermak is the so-called “Wagner case.” In the summer of 2020, Ukrainian intelligence conducted a brilliant multi-stage operation to lure a group of Russian PMC “Wagner” mercenaries (involved in crimes in Donbas) out of Belarus for the purpose of arresting them in Ukraine. The operation was in its final stage but suddenly collapsed: the Belarusian KGB arrested the Wagner group in Minsk because Moscow had been tipped off about their arrival in advance.

It later emerged that the order to postpone the final phase of the operation came from Zelenskyy himself – on Yermak’s advice. According to investigators, on the eve of the planned capture, Yermak persuaded Zelenskyy to delay the special operation, allegedly saying it could not be carried out “tomorrow, it must be canceled or postponed.” He reportedly justified it by asking, “Why provoke Putin?!” and the president followed his advice. The result: the operation failed, and the Russian terrorists escaped justice.

Officially, the authorities denied that such an operation had even been planned, which only fueled suspicions. Journalists hinted that the leak could have come from a phone call from the Presidential Office, as “what’s easier than calling a retired intelligence officer who communicates with the GRU leadership?” There is no direct evidence of Yermak’s involvement in the “Wagnergate,” but the suspicion remains – the story appears as a Russian intelligence operation to neutralize a dangerous Ukrainian special operation. Yermak’s role in this raises many questions.

Oleh Tatarov: flights to Moscow and the shadow of Yanukovych

Another key figure in Zelenskyy’s circle is Oleh Tatarov, deputy head of the Presidential Office responsible for law enforcement. His appointment in 2020 shocked the pro-European public, as Tatarov had been a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Internal Affairs under the Yanukovych regime and, at the height of Euromaidan, defended the security forces who shot activists.

Equally concerning are Tatarov’s Russian connections. An investigation by the “Skhemy” project (Radio Free Europe) revealed that after 2014, Tatarov, as a private individual, flew to Moscow at least nine times. He visited the Russian capital three times in 2017, four times in 2018, and twice in 2019 — the last visit occurring the day after Zelenskyy’s victory in the second round of the presidential election, on April 22, 2019. It was also discovered that in 2015 Tatarov traveled to annexed Crimea. The reasons for these trips are unknown; Tatarov himself called the information about his Moscow visits “fake” and denied any contacts with Russian officials. However, documentary evidence of his border crossings cannot be dismissed.

Importantly, direct flights between Ukraine and Russia did not exist after 2014 — Tatarov flew via Minsk, which required effort and clearly was not casual tourism. Despite these revelations, Zelenskyy continues to keep Tatarov in office and has publicly defended him. When journalists questioned the appropriateness of Tatarov’s role, the president emotionally replied that “Tatarov, together with Malyuk (head of the SBU), was taking down Chechens in Kyiv when you weren’t here… Do you want me to fire him so the Russians can kill him?”

This explanation is striking. On one hand, Tatarov may indeed have played a role in neutralizing Russian sabotage groups in the early days of the war. On the other hand, why is the public unaware of this, and does it justify all his questionable actions? Regardless of his merits, the fact remains: Tatarov is a former Yanukovych-era official with a history of trips to Russia. For Russian intelligence services, such a person is an ideal candidate for a “mole” or at least a channel of influence, as compromising material exists from the past. It is known that the FSB and GRU actively recruited personnel from Yanukovych’s circle during his flight to Russia. Is Tatarov’s presence in the Presidential Office really a coincidence? In a “Russian project” scenario, it is precisely through such individuals that Moscow could subtly gain information or influence decisions.

The story of Tatarov’s possible corruption (the case involving bribes from developers), which was strangely “buried” by law enforcement, is also linked by some to Moscow’s influence. Allegedly, discrediting anti-corruption agencies through Tatarov benefits only the Kremlin, as it undermines the West’s trust in Ukraine. In any case, Tatarov’s role and Zelenskyy’s refusal to dismiss him are perceived by many as indicators of pro-Russian tendencies within the Presidential Office.

Rostyslav Shurma: a “Trojan horse” from the former regionalists

Until September 2024, Rostyslav Shurma served as deputy head of the Presidential Office for economic affairs. He had a reputation as a successful manager (formerly director of the Zaporizhstal plant in the Akhmetov group) and was a new face in Zelenskyy’s team. However, his political roots are openly pro-Russian.

First, Rostyslav’s father, Ihor Shurma, is a well-known politician from pro-Russian forces. Since the 1990s, Ihor Shurma was an associate of Viktor Medvedchuk (Putin’s godfather), was a member of the SDPU(o), and later was twice elected as a people’s deputy from the Opposition Bloc (the former Party of Regions). In parliament, he became notorious for scandals: he did not stand to honor the victims of the Holodomor, refused to vote for recognizing the “DPR/LPR” as terrorist organizations and Russia as an aggressor, justifying his stance by saying “European countries did not recognize this.” In other words, Shurma’s father openly transmitted Kremlin narratives. It is clear that Rostyslav grew up in such an environment, and although he is younger and publicly keeps a distance from politics, the influence of his surroundings cannot be ignored.

Second, Rostyslav Shurma built his career in eastern Ukraine, an industrial region traditionally marked by strong pro-Russian sentiments. From 2015 to 2019, he headed the Zaporizhzhia regional branch of the Opposition Bloc — the same party as the former regionalists. In other words, he came from the “fifth column.” Before his appointment to the Presidential Office, Shurma publicly distanced himself from politics, presenting himself as a technocrat. Yet, as in Tatarov’s case, his past raised concerns: was this a concession to the pro-Russian lobby? The Kremlin has long sought to maintain influence over Ukraine’s economic policy through its people, and the position of presidential economic advisor was a strategic post.

Shurma remained in the Presidential Office for almost three years. He resigned in September 2024, officially as part of a broad reshuffle, but unofficially due to a series of scandals. Notably, it emerged that his brother, Oleh Shurma, conducted business even in occupied territories during the war: his companies continued receiving “green tariffs” for solar power plants that fell under Russian occupation. Although Rostyslav denied any wrongdoing, the situation appeared at least as a conflict of interest — or even indirect funding of the enemy. Meanwhile, Shurma’s father left the country after the invasion (to Germany) — it is worth noting that many controversial figures from the OPZZh fled under the protection of Russia or Belarus.

All these factors make Rostyslav Shurma a highly controversial figure. From the perspective of Russian interests, his presence in Zelenskyy’s inner circle was advantageous: a person from the pro-Russian orbit with access to internal decisions and economic data. Whether Shurma was a conscious agent of influence or merely a technocrat sympathetic to the “Russian world” remains an open question. Yet his example illustrates that Zelenskyy’s team was not monolithic and included individuals whose worldview strangely aligned with Moscow’s narratives.

Tymur Mindich: the President’s “wallet” with diamonds in Russia

Among Zelenskyy’s closest circle is businessman Tymur Mindich, a long-time friend and partner from “Kvartal-95.” Mindich has jokingly been called Zelenskyy’s “wallet” due to his influence and financial support. He holds no official positions but features in many behind-the-scenes stories. In the context of Russian ties, it is important that Mindich conducted active business in Russia even after the war in Donbas began — specifically in the precious stones sector.

According to journalist and deputy Yaroslav Zheleznyak, Mindich was a co-owner of the Russian company New Diamonds Technology, which produced synthetic diamonds. This business was organized at the suggestion of oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskyi: in 2014, Kolomoyskyi seized the state-owned Kyiv Diamond Processing Plant (“Izumrud”) in Ukraine, and a year later transferred the asset to Mindich, who launched a diamond-growing laboratory based on it. Almost simultaneously, a related company, NDT (New Diamonds Technology), appeared in Russia, also controlled by Mindich through offshore structures. Mindich remained a co-owner of the Russian laboratory at least until the end of 2024, i.e., during the full-scale war. Distribution of these Russian diamonds was handled by the London firm Meylor Global, also linked to Mindich.

In other words, even while Russia was attacking Ukraine, the president’s friend was making large profits in Russia and paying taxes to the Russian budget (amounting to millions of dollars). This is a documented fact, made public in October 2025. It takes on particular significance against the backdrop of Zelenskyy’s anti-corruption efforts: at that time, NABU was close to bringing charges against Mindich in other cases. An interesting detail: in July 2025, during covert investigative actions, anti-corruption authorities recorded Mindich — and possibly Zelenskyy himself — in the same apartment, where the president’s birthday was being celebrated. This location had been equipped with surveillance as part of the Mindich case. According to journalists, these recordings could have harmed Mindich and cast a shadow over the president. Following this, there was pressure from the authorities on NABU and SAP, an attempt to change leadership, which sparked public protests. Many linked this attack to the desire to protect Mindich from exposure.

Thus, we have a situation where Zelenskyy’s close friend conducts business with Russia, potentially creating a vulnerability for the president. Mindich could have become an ideal channel for bribery or influence — if Russian intelligence is aware of his operations (and they almost certainly are, as at minimum the Russian tax authorities knew about the diamonds). Moreover, in the midst of the war, he is under investigation by Ukrainian anti-corruption agencies, who are likely aware of his international dealings. The “insider-outsider” system in Russia regarding Mindich seems not to have worked: the Russians did not obstruct his business or seize his assets, which suggests they considered him either “one of their own” or useful. This is a telling signal. If Zelenskyy continues to maintain a close friendship with such a figure, it raises questions: does he understand the scale of the risks? Or perhaps he simply does not care, seeing no problem in it? Both possibilities are cause for concern.

The Shefir brothers: affinity for the “Russian world”

Serhiy and Borys Shefir have been Zelenskyy’s closest business partners since his comedic days. They helped establish the “Kvartal-95” studio, wrote scripts, and produced projects. After Zelenskyy’s election, Serhiy Shefir became the president’s chief aide, while Borys remained in show business. Although they did not formally hold government positions, their influence and stance are also significant.

The Shefir brothers effectively symbolize a generation of post-Soviet entertainment figures who long considered the Russian cultural space their own. Before 2014, “Kvartal-95” had a huge market in Russia: concerts, tours, joint film projects, and broadcasts on Russian TV. Russia’s aggression forced a choice: many Ukrainian artists boycotted Russia. However, Zelenskyy’s team initially tried to straddle both worlds. In 2018, when the TV series “Svaty” was banned in Ukraine (due to an actor on the blacklist), Zelenskyy and the Shefirs protested, calling it unnecessary politicization. They openly stated that “art is above politics” and that ties with Russian culture should not be severed.

A telling example is Borys Shefir’s 2020 interview, given after the war had already begun. Borys admitted that he loves the Russian language and culture, opposes the removal of Pushkin monuments, and supports friendship with Russia. In his words, “we are fighting Putin, not Russia,” and “we should be friends again as soon as normal people come to power there.” He also compared the EU to the USSR, saying the bureaucracy is similar.

Effectively, Borys Shefir expressed views close to Kremlin narratives about a “single people” and “waiting for Russia to come to its senses.” This caused a scandal: the brother of the president’s closest aide was nostalgic for friendship with the aggressor. Serhiy Shefir had to publicly state that he completely disagreed with his brother and that Russia is an aggressor that must answer for its crimes. This episode revealed a deep mental split even among Zelenskyy’s friends: Serhiy, fortunately, understands the reality of the war, while Borys remains captive to the “Russian world.”

It is worth noting that the Shefir brothers and other “Kvartal-95” associates conducted business in Russia without issues before 2014. Films produced by “Kvartal-95” were released in the Russian market, with funding from Russian film studios. It is known that even after 2014, some projects formally controlled by the Shefirs (through offshore companies) continued to work with Russia.

The Pandora Papers revealed that before the elections, Zelenskyy transferred his share of an offshore company to Serhiy Shefir, indirectly linked to payments from Kolomoyskyi’s structures (more on this below). In other words, Shefir became the nominal owner of Zelenskyy’s share in the “Kvartal” business empire, and through this system, funds of unknown origin were received. Opponents claimed that $40 million from Kolomoyskyi’s structures flowed into Zelenskyy’s and his associates’ offshore accounts between 2012 and 2016. The existence of such shadow finances created potential dependence of Zelenskyy’s team both on oligarchs and on Russians (as Kolomoyskyi also earned in Russia).

In summary, the Shefir brothers embody the part of the president’s circle that, at least until recently, did not see Russia as an enemy. Borys openly wishes to “return to the way things were,” while Serhiy, as a public official, adhered to a patriotic line — but he is no longer in government (having left his post in 2024). Volodymyr Zelenskyy has distanced himself from Borys Shefir, who went abroad and has not been in contact with the president since 2022. This reflects positively on Zelenskyy as a leader, showing he can break ties with friends who have not accepted the reality of the war.

However, the fact that such individuals were among Zelenskyy’s first allies raises a question: was his own worldview for a long time also colored by illusions of a “brotherly people”? If so, Russian intelligence could have skillfully exploited this even in the early stages of Zelenskyy’s career.

David Arakhamia: Russian-born with mysterious passports

David Arakhamia is the head of the “Servant of the People” faction in the Verkhovna Rada and Zelenskyy’s trusted person in parliament. His life story is unusual and also linked to Russia. Arakhamia was born in 1979 in Sochi (RSFSR) into a mixed Georgian-Armenian family. He spent his childhood in Abkhazia, but after the 1992 war in this Georgian region, his family moved to Ukraine as refugees, settling in Mykolaiv. Formally, David acquired Ukrainian citizenship only in 2015 — until then, he had lived in Ukraine for more than 20 years as a foreigner, likely holding Georgian, American, and Russian passports.

In the business world, Arakhamia was known under the pseudonym David Braun — under this Anglicized name, he ran an IT business in the U.S. and other countries. This change of name and citizenships has fueled numerous theories. Zelenskyy’s opponents mocked that “it’s unclear who the real Arakhamia is — David the Georgian, David Braun the American, or a Russian.”

From a security perspective, a vulnerable point is that Arakhamia was born in Russia and has relatives there. He has repeatedly stressed his commitment to Ukraine, but adversaries can easily exploit his biography. Perhaps for this reason, Arakhamia was one of the key negotiators with the Russians at the start of the war: psychologically, it is easier for the Kremlin to deal with someone born in Russia. In March 2022, he led the Ukrainian delegation at the peace talks in Istanbul. This was a risky mission, during which intelligence operations could have been at play. It is known that participants in those talks were even targeted for poisoning.

That said, there is no direct evidence of pro-Russian sympathies on Arakhamia’s part — he publicly maintains a pro-Ukrainian and pro-American stance. However, the image of a politician with “multiple passports” (even though he officially denies holding a second citizenship) unsettles the public. Russian propaganda has alternately accused him of arms trading or other schemes — most likely to discredit him. Moscow itself probably does not consider Arakhamia “one of their own,” so this example is less striking than others. Nevertheless, it confirms a broader trend: within Zelenskyy’s circle, there are practically no individuals without some Russian connection in their background.

Mykhailo Podolyak: brother – colonel in Russian GRU

Presidential Office advisor Mykhailo Podolyak became known as Ukraine’s spokesperson during the war and a staunch critic of Moscow. This made the revelation about his family connection even more shocking. In the summer of 2024, Podolyak’s older brother, Volodymyr Podolyak, a career officer in Russia’s GRU with the rank of colonel, mysteriously died in Moscow. Russian opposition media (SOTA project) reported that the 59-year-old elder Podolyak was buried with honors, including a wreath “from the employees of the GRU Special Training Center.” His grave shows he was awarded the “Participant of the Special Military Operation” medal, established by the Russian Ministry of Defense after the 2022 invasion. This means the advisor’s brother participated in the war against Ukraine — either as an intelligence overseer or in another capacity.

Moreover, an intriguing fact emerged: Volodymyr Podolyak was part of the Russian delegation at the peace talks in Istanbul in March 2022, while Mykhailo Podolyak represented Ukraine. Two brothers — sitting on opposite sides of the negotiation table between Ukraine and Russia. It reads like an incredible story, but the data are confirmed by documents.

Volodymyr Podolyak’s grave (brother of Mykhailo Podolyak) in a Moscow cemetery in 2024, adorned with a wreath from the Russian GRU. The elder Podolyak was a colonel in Russian military intelligence, awarded for participating in the “special military operation” against Ukraine.

Mykhailo Podolyak admitted that he had not maintained close contact with his brother since 2014 (when Russia occupied Crimea) and that they spoke only once a year on birthdays. After the news of Volodymyr’s death in May 2024, Mykhailo bitterly wrote that his brother “took the side of evil and died as an enemy” — clearly a personal tragedy.

From a state security perspective, however, the question is whether the Kremlin could have used the existence of such a brother to pressure or recruit the younger Podolyak — through blackmail or attempts to build trust. It is known that Russians often take relatives of Ukrainian officials hostage or exert pressure to make them more compliant.

In Podolyak’s case, nothing of the sort occurred publicly. Russia did not reveal his brother’s identity until his death, possibly because Volodymyr, as an intelligence officer, requested that family ties remain undisclosed to avoid jeopardizing his mission.

This case highlights more of a moral dilemma and personal drama than direct betrayal: Mykhailo Podolyak serves Ukraine faithfully, while his brother served Russia and was eventually likely neutralized by his own side (circumstances of death undisclosed).

For an external observer, this fact underscores a broader pattern: within Zelenskyy’s inner circle, some officials have close relatives in Moscow working for Russian structures, yet nothing happens to them — no arrests, no public pressure. This suggests that Moscow does not regard these officials as mortal enemies; otherwise, families could have been targeted. In Podolyak’s case, the logic is ambiguous (his brother was a valuable figure for Russia, so he was left untouched for the time being). Overall, however, the trend — “relatives in Russia remain unharmed” — can be observed in several other figures as well.

General Oleksandr Syrskyy: family in Russia, defender of Ukraine

Commander of the Ukrainian Ground Forces (as of 2022–23), General Oleksandr Syrskyy, is one of the military heroes of the war, leading the defense of Kyiv and the liberation of Kharkiv region. On the surface, he seems like someone Moscow would certainly wish dead. However, there is an interesting nuance: Syrskyi was born and raised in Russia, in the family of a Soviet officer, and as of 2023, his parents and brother still live in Russia. He graduated from the Moscow Higher Military Command School during the USSR era and transferred to serve Ukraine in the 1990s, when part of his unit ended up on the territory of independent Ukraine. In other words, his biography is typical of many senior Ukrainian commanders: Russian by birthplace who became a Ukrainian patriot in service.

In the 2020s, Syrskyy’s father – an 86-year-old retired colonel – suffered from a serious illness, and reports emerged that Syrskyy had sent his parents to Moscow for treatment. From a security perspective, this situation is delicate: the Syrskyy family would be an ideal target for the FSB. However, as far as is known, the Russians did not take any public actions against them. Moreover, it seems the general’s father received some medical assistance. It is possible that the Kremlin deliberately refrained from repressing the Syrskyy family – perhaps hoping that the general might hesitate or even switch sides in a critical moment to save his relatives. If so, they clearly miscalculated: Oleksandr Syrskyy remained loyal to his oath and inflicted significant defeats on the Russian army.

Yet the very fact that the closest relatives of a senior Ukrainian commander live safely in Russia confirms a broader trend: Russia does not always punish the relatives of Ukrainian officials – whether out of humanitarian concern (unlikely) or strategic calculation. In any case, it is suspicious. According to the logic of a brutal war, if the Kremlin considered Syrskyy an irreconcilable enemy, his family could have disappeared in some Lubyanka basement. Since this did not happen, it is possible that Russian intelligence still harbors an illusion of influence through family ties.

So, we have reviewed several key figures from Zelenskyy’s team. Almost all of them:

Either had close ties with Russia in the past (Yermak – father was a GRU officer and business with a Russian advisor; Tatarov – frequent trips to Moscow; Shurma – father was Medvedchuk’s ally; Mindich – business in Russia during the war; Zelenskyy/Shefir brothers – many years working for the Russian market, cultural integration);

Or have close relatives in Russia who remain unharmed (Podolyak, Syrskyy, partially Yermak – Russian mother);

Or were themselves born/lived in Russia (Arahamia, Syrskyy) or Belarus (Podolyak started his career there).

Of course, a person’s biography alone does not make them a traitor. Ukraine is multinational and has long-standing ties with Russia, so it’s not surprising that some have relatives in Russia, studied in Moscow, or did business there. But the key point is this: in critical moments, most of these figures remained in their positions and faced no “reprisal” from Russia. The Russian state always eliminates such people (like former Russians who sided with Ukraine, e.g., FSB officer Belov or a pilot who defected with a helicopter) – yet here, there is silence. Coincidence…?

How could it happen that at the critical moment of the February 2022 attack, Ukraine was so weakened from within? Gradually, society began searching for answers and stumbled upon uncomfortable questions about President Zelenskyy’s inner circle. As we now clearly see, many in the team making decisions before the war had complicated backgrounds — people who, under normal circumstances, would have been flagged by the SBU as potentially working for enemy interests (if the service itself had been purged of Moscow’s agents).

These individuals occupied — and still occupy — key positions and could have influenced preparations for the invasion and the subsequent slow loss of Ukrainian territory over the following years. Could they have been Kremlin “Trojan horses,” deliberately executing a scenario of surrender? At the very least, a number of facts suggest such a possibility.

In intelligence work, there is a concept of “insider versus outsider”: embedded agents are protected, unlike openly hostile elements. It appears that people in Zelenskyy’s circle are, at minimum, not viewed by Moscow as irreconcilable enemies. And that is a troubling signal — because Moscow has always promoted its “insider” to the top echelons of power in countries within its sphere of geopolitical influence.

Think about it.

Tags: mindich case Russia influence russian agents Shurma background Tatarov Moscow trips Ukraine government ties Ukrainian Politics Zelenskyy circle

![The Kyiv Instytutska Street massacre during the Maidan Revolution of Dignity, where Berkut’s “Black Company” shot and killed unarmed protesters. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/photo-1-480x270.png)

![Visitors at the “Thank You With All My Heart” Ukrainian exhibition at the Council of Europe, featuring the Great Amber Heart and powerful war art. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/heart-300x171.png)

![Ukrainian Roboneers and Latvian partners at the signing of a defence robotics and underwater technology cooperation memorandum. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/oboronka-300x168.png)