Former Commander-in-Chief Valeriy Zaluzhnyi recently described the current state of the Russia-Ukraine war as a “deadlock,” despite ongoing activity along the front. Ukraine’s ambassador to the UK noted that Russia continues to seek ways to break this stalemate, while analysts at DeepState observed that Russian advances in September slowed by nearly half compared to August. Although these figures might indicate that Ukraine has managed to restrain the enemy’s momentum, the situation on the battlefield is far more complex. Ukrainska Pravda spoke with soldiers and commanders to uncover the key challenges preventing the Defense Forces from effectively halting Russian pressure.

In his recent article, former commander-in-chief Valeriy Zaluzhnyi stated that despite a significant number of events on the front since 2022, the current situation on the battlefield of the Russia-Ukraine war can still be described as a “deadlock.” At the same time, Ukraine’s ambassador to the United Kingdom added that there is a consistent trend of Russia trying to break out of it.

Meanwhile, the analytical project DeepState noted that the pace of the occupying forces’ advance in September slowed by almost half compared to August.

On the surface, such statistics might suggest that the Defense Forces have found a way to slow the creeping advance of the Russians. However, in reality, the situation cannot always be calculated statistically or represented in colors on maps.

Ukrainska Pravda spoke with military personnel both on the front lines and in headquarters to identify the main problems that are preventing the Defense Forces from holding back Russian pressure on the front.

Infantry shortage

The shortage of personnel in the Ukrainian army has long ceased to be a secret. The winter–spring period of 2022 is over, and the lines of volunteers at military enlistment offices are a thing of the past. Issues with mobilization and AWOL have been in the public eye for months.

Although information about the actual numbers of understrength units is classified, it is enough to visit the “Vacancies” section on ReservPlus to understand that the Defense Forces need people.

The most in-demand positions in the army are mechanics, drivers, drone operators, medics, artillery specialists, repair technicians, and others.

In this text, we decided to focus on the most urgent problems facing the Defense Forces.

The most acute need directly on the front line remains infantry. At the current stage of the war, when operating heavy equipment is extremely difficult, the role of soldiers in the trenches has grown exponentially. When there are not enough of them, organizing defense becomes challenging.

Due to the personnel shortage, many units cannot hold their positions, fully repel Russian attacks, rest adequately, or conduct necessary rotations. As a result, commanders on the ground are forced to prioritize certain sectors, leaving other areas less protected.

Example:

Infantry shortages are being recorded along many sections of the front. For instance, it is currently most acute in the Novopavlivka direction (at the junction of Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, and Zaporizhzhia regions). The Russian forces are taking advantage of this issue in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, applying an infiltration tactic over the past few months. This involves advancing in small tactical groups through understrength positions of the Defense Forces.

Due to the numerical superiority of Russian infantry, Ukrainian fighters are often forced to avoid direct engagements, which leads to the effective intermingling of opposing positions. As a result, OSINT maps are showing more and more gray zones that are not fully controlled by either side.

Gaps between positions and the absence of a stable line of contact (LoC)

A consequence of the problem described above is that there are increasingly fewer personnel to man infantry positions. As a result, the distance between neighboring positions can be 200–300, 500–700 meters, and sometimes even a kilometer.

For comparison, in peaceful Kyiv, 500 meters is the distance from St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery to Saint Sophia Cathedral. One kilometer stretches from St. Michael’s to the Golden Gates. On the front, this is an enormous distance—essentially a gap through which enemy infantry can pass.

Captured Russian soldiers have calmly shared in interviews, for example, that while traveling to Pokrovsk in July 2025, they did not encounter any armed resistance from Ukrainian forces. Most likely, along their route—from Selydove through Zvirove, a village southwest of Pokrovsk, all the way to the city’s entrance—there was minimal infantry presence, and in some places, there may have been none at all.

“In the zones of brigades N and M,” an officer from one of the brigades on the Pokrovsk direction told Ukrainska Pravda, “and honestly, we have these gaps too. There are positions that exist purely for show—mangled, wounded, or ‘Cargo 300’ soldiers. They are there so that people above can feel pleased that we have positions in that area.”

The creation of numerous gaps between Ukrainian infantry positions and the penetration of Russian forces through these gaps deep into our defenses has formed another trend at the current stage of the war—the absence of a stable line of contact (LoC).

This means that Defense Forces positions are closely interspersed between enemy positions—like on the Dobropillia salient—or that infantry, rather than enemy sabotage-reconnaissance groups, penetrate front-line towns, as in the cases of Kostiantynivka or Yampil.

“I’m not used to operating like this. I’m used to having infantry positions set up, with subsequent units behind them. Now, there is no LoC at all,” one of our sources in the 19th Army Corps said, clearly frustrated.

Due to the lack of personnel on the front line, drone operators and mortar crews, stationed 3–5 kilometers behind the forward edge, are forced to act as infantry.

“My guys working with the 82-mm mortar have already been engaged in combat,” added the same source.

In the worst cases known to Ukrainska Pravda, Russian forces even reach artillery positions—10–15 kilometers from the LoC.

Difficult transition to corps

The transition to corps in the Ukrainian army was announced back in winter.

In the spring, Ukrainska Pravda conducted a detailed analysis of the reform, explaining why the Armed Forces of Ukraine decided to undertake a large-scale restructuring in the midst of active combat operations.

On October 1, the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Andriy Hnatov, stated that the transition to a corps structure had been completed and that, “despite some nuances,” all newly formed corps were already carrying out tasks within their designated groupings.

Many of the military personnel interviewed by Ukrainska Pravda called these statements premature.

Formally, all corps have indeed been established; however, the level of understrength staffing—even within the headquarters of the newly formed units—remains quite high.

Supporters of the reform cited the key advantage of transitioning the Defense Forces to a corps system as the establishment of stable command structures. Yet this has not yet occurred, as temporary operational commands (OTU), tactical groups (TGR), and similar formations still exist in some form on the ground.

Moreover, there are questions regarding the transition to carrying out tasks by corps exclusively within their designated sectors of responsibility. On many sections of the front, a full transition has not occurred, while the General Staff already plans to create additional structures, such as Assault Forces and Anti-Aircraft Drone Systems within the Air Forces.

In conditions of an overall personnel shortage and an unfinished transition to a corps system, finding resources for new military formations will be quite challenging.

Example:

The best evidence that statements about the completion of the transition to a corps system were premature is the Dobropillia direction, which Ukrainska Pravda recently covered in detail.

This sector is assigned to the 1st Corps of the National Guard “Azov,” yet in practice only one brigade, “Chervona Kalyna,” which is directly subordinate to this unit, is operating there. All other units are attached support elements.

We are not evaluating the results of combat in this direction; we are only pointing out the fact that, in reality, the corps-based approach has not yet been fully implemented.

Micromanagement by the commander-in-chief and constant changes in the military command structure

In June 2025, Ukrainska Pravda was the first to report how Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrskyi resorts to hands-on management of the front. He personally chooses—and sometimes removes—corps commanders, decides which brigades receive reinforcements and in what numbers, issues tasks to battalions that should be set by brigade commanders, and so on.

Over the past three months, the situation of the front being dependent on the instructions of a single individual, according to Ukrainska Pravda and its sources in the Defense Forces, has only become more complicated.

Initially, Syrskyi began regularly visiting and “adjusting” the actions of units on the Dobropillia salient, which the Defense Forces are currently “trimming.” According to public mentions by the commander himself, over the past three and a half months, he has traveled to meetings and consultations with local commanders eight times.

According to Ukrainska Pravda, it is the commander-in-chief and also the commander of the Air Assault Forces, Oleg Apostol, who are the key people assigning tasks to assault units in this direction — despite the fact that the 1st National Guard Corps “Azov” should be in charge here.

Then the president announced the creation of the aforementioned Assault Forces, which, in all likelihood, will be a consolidation and scaling up of units directly subordinate to Syrskyi.

Thus the commander-in-chief will gain at his disposal a mini‑army of the strongest assault units. Or, as opponents of the new branch call it in conversations with Ukrainska Pravda, “Syrskyi’s guard” or “Syrskyi’s pocket troops.”

To be fair, not everyone in the army is so critical of the idea of creating Assault Forces. Some commanders told Ukrainska Pravda they consider the decision entirely logical and even overdue.

“The 3rd, 5th, 92nd, which are called assault units, fight as infantry. And these Assault Forces, as I understand it, are supposed to be different. A sensible decision,” one former brigade commander told Ukrainska Pravda.

“The problem isn’t that Syrskyi’s conditional reserve will expand so much—every commander should have a reserve, and the commander-in-chief even more so. The problem is that this reserve exists only with Syrskyi. No other commander has anything like it; maybe it exists on paper, but in reality—it doesn’t.

Syrskyi wants it—he sends his reserve to Sumy, he wants it—he sends it to Dobropillia. And when the 7th Air Assault Corps requested 4–6 assault groups for the Pokrovsk direction, the combat order from the commander-in-chief said: ‘Create them yourselves,’” one well-informed colonel told Ukrainska Pravda indignantly.

The creation of the Assault Forces is not the only recent development worth mentioning in the context of the commander-in-chief’s management decisions.

Ukrainska Pravda learned that at the end of September, Syrskyi disbanded the operational-strategic grouping of troops “Dnipro” (formerly “Khortytsia”), which had been commanded for eight months by Mykhailo Drapatyi.

The “Dnipro” operational-strategic grouping, more or less, was responsible for almost the entire active front from Zaporizhzhia to Kharkiv, given the high level of involvement of the commander-in-chief and the General Staff. For example, it handled the distribution of shells among brigades. All OSG functions now fall on the troop groupings—superstructures that emerged with the formation of corps—and on the corps themselves.

What will happen to Drapatyi? He will remain commander of the Joint Forces and move with his team to one of the northeastern front sectors, where he will head a troop grouping. His zone of influence and responsibility will be reduced by roughly half.

One of Ukrainska Pravda’s sources, an experienced senior officer clearly dissatisfied with the new changes, called Syrskyi’s actions a way to “eliminate a competitor.”

“On one hand, it’s a logical step, because the OSG layer disappears—it should disappear with the transition to corps. On the other hand, this step achieves nothing, because Syrskyi still commands everything. What reforms? No corps is yet commanding its own set of troops; no one has the authority to maneuver. We ran away from tactical groups (TGRs), and yet in the Serebriansky Forest, they created one again,” the colonel shared with Ukrainska Pravda.

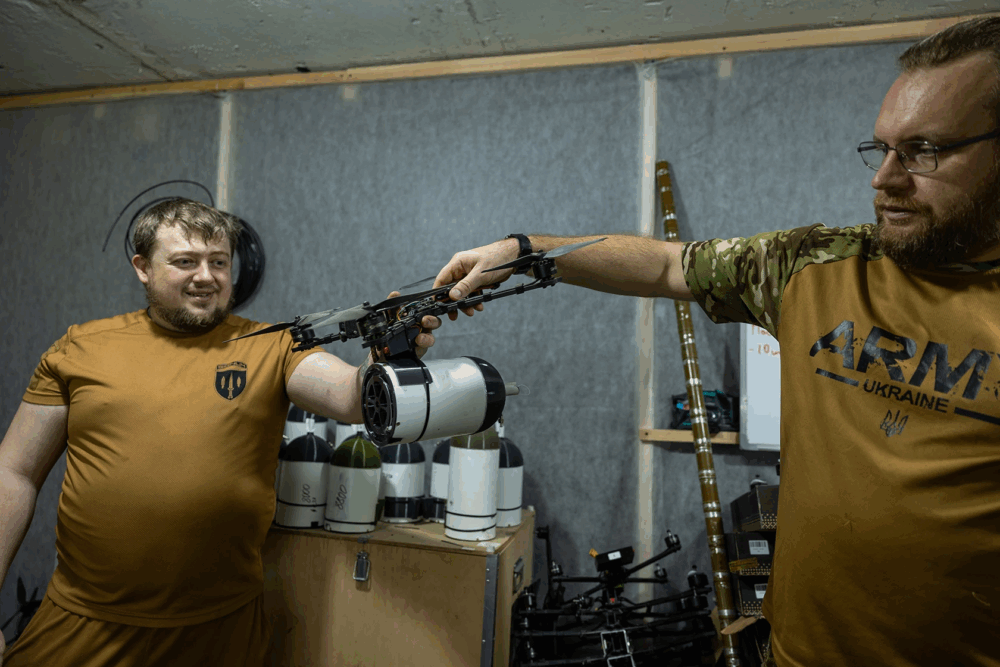

Drone challenges

This section is the most debated, as both Ukrainian and Russian sources often make completely opposing claims regarding the adversary’s advantage in UAVs. Moreover, each side frequently believes that the drone advantage lies with the opponent.

In reality, such a discrepancy in assessments is explained by the fact that the question is posed in general terms, rather than by specific types of UAVs.

Looking at the situation in detail, one key point emerges—Ukraine still leads in innovation, but the Russians rely on mass production, which is increasingly being felt both at the front and in the rear.

Since the start of the full-scale war, both sides have created separate Drone Forces and are scaling up their UAV units. On the Ukrainian side, the “Drone Line” is being actively developed, while the Russians are concentrating all efforts on the Rubicon center—elite UAV deployment units that appear on the hottest sections of the front and create significant problems for Ukrainian forces.

Another major challenge for the Defense Forces is that Russia has sharply increased the production of long-range drones, which are generally referred to in Ukraine as “Shaheds.”

Examples:

A striking example of Russian UAV deployment is the displacement of Ukrainian forces from the Kursk region, when the “Rubicon” units systematically destroyed Defense Forces logistics and forced them to abandon the occupied territory.

Russia is now using the same tactic in Donetsk, significantly complicating Ukrainian Armed Forces logistics along key supply routes, such as the Izium–Sloviansk road.

The scaling up of “Shahed” production has already led to daily attacks deep inside Ukrainian territory, which not only overloads air defense systems in major cities but also increases risks for critical infrastructure, particularly in the energy sector.

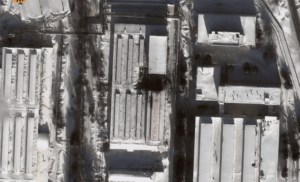

Rear units pulled back from the line of contact

Due to increased activity by Russian aviation and drones, from roughly late spring to early summer this year, Ukrainian army support units began to move farther away from the line of contact (LoC).

Ukrainska Pravda learned about the first such case under tragic circumstances. At the end of April, while traveling to work with military personnel, we witnessed another bombing of Druzhkivka. A mechanized brigade’s motor pool was engulfed in tall flames following a strike by Russian KABs. The next day, the base was hit again.

By order of a senior commander, all support units were required to move 40–50 kilometers back from the LoC.

For commanders of rear units, this decision means that in conditions of already limited resources—especially fuel—the logistics chain becomes longer and more complicated.

“Previously, to deliver a few tons of fuel, I would spend 40 liters and a couple of hours. Now—it’s 300 liters and almost a full day,” one logistics commander told Ukrainska Pravda.

At the same time, for a senior commander, this directive is a way to protect people—which is most important—as well as military equipment.

Over the course of two months, Ukrainska Pravda journalists went on a new assignment to Donetsk and realized that even if the targeted KAB strikes had not occurred, rear units would inevitably have moved farther from the LoC. Russian FPV drones now dominate the area up to 10–15 kilometers deep and have begun targeting vehicles on key roads. All logistics operations have become extremely risky.

Along with support units, the soldiers themselves have started looking for housing farther from the LoC. As a result, some personnel fighting in Donetsk now live in Kharkiv and Dnipropetrovsk regions, which significantly increases travel time to their positions.

Behind the latest “positive” news from the Dobropillia salient, which the commander-in-chief reports almost daily, lies an extremely difficult situation for the Defense Forces near Pokrovsk and Myrnohrad, in Kupiansk, on the Novopavlivka and Lyman directions, and near Kostiantynivka.

Once rear cities in Donetsk, such as Druzhkivka, are now becoming operating zones for Russian FPV drones. Dobropillia is being dismantled house by house, street by street. The front is moving weekly through Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia regions.

Across Donetsk Oblast, only two large cities remain where life is still active, though now under nearly daily KAB and drone strikes.

At the same time, military leadership at various levels turns a blind eye to quite obvious problems within the Ukrainian army, while the Presidential Office, without whose approval no decision is made in this country, avoids risking its ratings and allows the leaders of draft-dodger networks and their supporters to raise their heads.

Meanwhile, gaps between infantry positions continue to widen.

Tags: frontline gaps infantry shortage logistical challenges military analysis Russian advance ukraine war war investigation

![The Kyiv Instytutska Street massacre during the Maidan Revolution of Dignity, where Berkut’s “Black Company” shot and killed unarmed protesters. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/photo-1-480x270.png)