Starlink has become vital for Ukraine’s civilians, military, businesses, and humanitarian operations. Adaptis adapts terminals for mobility, protection, and crisis scenarios, while new regulations and white lists shape secure usage.

Over nearly four years of full-scale war, Starlink satellite communication has become a tool for Ukraine used by civilians, the military, businesses, media, and humanitarian organizations — both in combat zones and during blackouts in the rear. Recently, the government began regulating the use of terminals, including through registration and access mechanisms via “white lists.” The main reason for this is to prevent Russians from using Starlinks to control drones.

24 Kanal spoke with Anton Sadykov, CEO of Adaptis, a company that adapts Starlinks for Ukraine, about how their use has evolved, why there was a demand for “adaptation for Ukraine,” and how the market is responding to the new rules. In the conversation, he describes the journey from humanitarian requests to production solutions and evaluates the consequences of stricter terminal control for civilian and business users.

Sadykov also touches on official import, interaction with state institutions, and the prospects for alternatives to low-orbit communication — from the Amazon LEO project to European and Chinese systems.

From Humanitarian Request to a Dedicated Project: How Did the Company Start?

Sadykov explains that the launch of Adaptis was a direct response to a practical need that arose in humanitarian work — it was necessary not only to deliver aid but also to provide communication where it was critically needed. According to him, the first solutions emerged in situations where ready-made providers could not be found either in Ukraine or in Europe, and the timing and cost of imported services created risks.

“Our company was founded three years ago. It was a response to a request from World Central Kitchen — an organization that has been working in Ukraine: preparing hot meals for Ukrainians, assembling food packages, and helping on-site after attacks. I was part of this team. When territories in the Kherson region were liberated, we needed not only to deliver food there but also to bring communication so that people could connect with the outside world.” — Anton Sadykov

As the head of Adaptis explains, at an early stage he was tasked with organizing the delivery of communication to liberated and frontline areas of the Kherson region, and he quickly realized that “just buying and installing a Starlink” didn’t work. He explains that early-generation terminals were large, and installing them on vehicles made them visible from a distance.

Sadykov notes that at that time the terminals were sold at inflated prices, and the offer from a small American team involved long waiting times — several weeks for production and roughly the same for delivery. According to him, in conditions of uncertainty, this was seen as too risky, so he decided to handle the technical side himself and later found a contractor who could implement his plan.

During testing, the head of Adaptis says it became clear that the solution was needed not only for humanitarian missions — there was also demand from the military, and the concept of using Starlink on vehicles had not been systemically addressed by anyone. He adds that after the first kits for World Central Kitchen, the team decided to formalize it as a separate full-scale project, which later evolved into a company under a different name (initially, he says, it was called Starkit).

How Was Starlink Modified? Encapsulation, Protection, and Quick Relocation

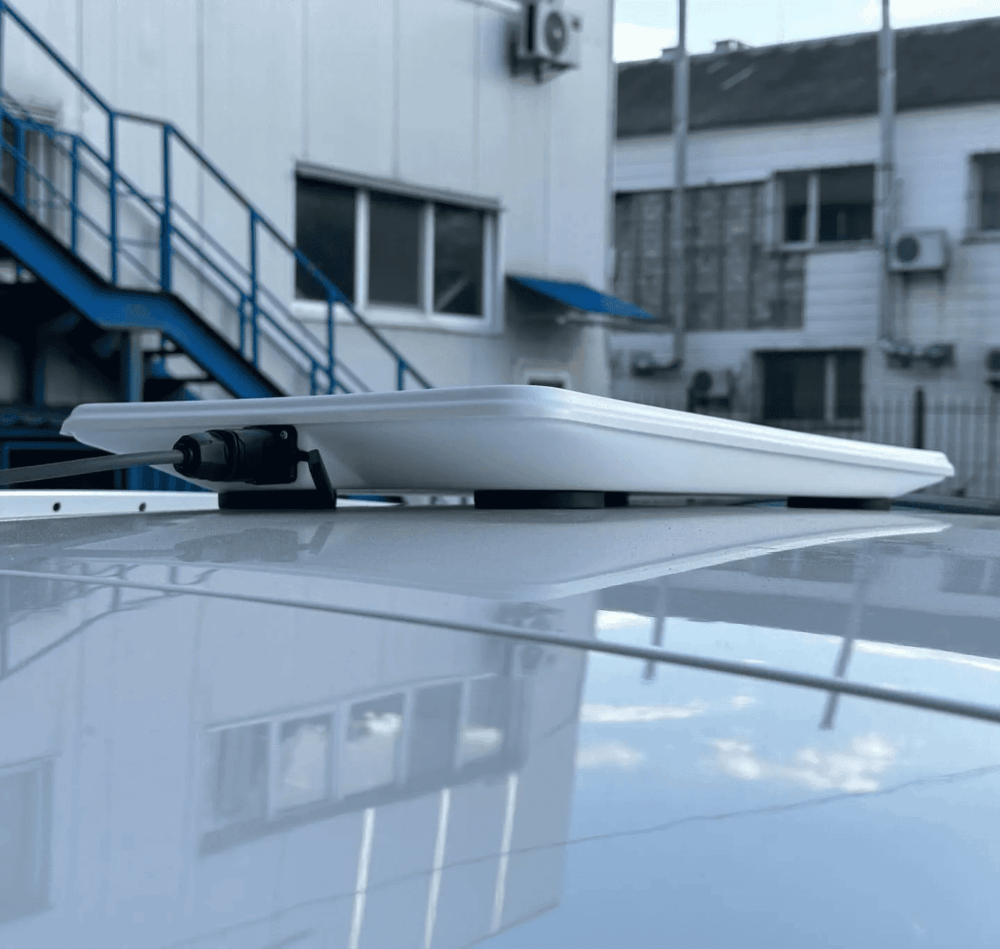

According to Sadykov, in the first months of widespread Starlink use on vehicles, the key problem was physical: the “mast,” wind resistance, shaking and breakage, as well as the inability to operate reliably while moving. He refers to widely circulated videos from the early days of the war, where soldiers held terminals by hand from truck beds or vehicle interiors, or antennas were mounted on buses in a very conspicuous way.

“We found a way to safely disassemble a Starlink terminal and encapsulate it differently — providing additional protection, taking into account our pothole-filled roads and specific usage conditions. The ‘field use’ envisioned by the manufacturer is not the same as the ‘fields’ in Ukraine, where people are under constant fire and threat.” — Anton Sadykov, CEO of Adaptis

The interlocutor states that after encapsulation, the next requirement was mobility — the solution shouldn’t “tie” the terminal to a single vehicle. As the head of Adaptis explains, in real scenarios a unit might arrive in one vehicle, leave it behind, move to another position, or switch vehicles — and the terminal needs to be quickly removed and relocated.

According to Sadykov, he considers fixed mounting a mistake precisely because of such changing circumstances. That’s why the team looked for a mechanism that would allow the kit to be installed on “any vehicle” without compromising reliability. He emphasizes that the requirement was practical: the terminal must withstand speed and not detach while moving.

The interlocutor also emphasizes a change in the approach to “modifying” the terminal itself. According to him, in the early days (when the company was called Starkit) it was necessary to physically disassemble the Starlink and alter its structure. Now, as Sadykov explains, the approach is different: the terminal remains intact, the original warranty is preserved, and the Adaptis “case” or housing protects it externally without interfering with internal systems, unless a special task requires a customized setup.

“White Lists,” Registration, and What This Means for Users

Sadykov views the increased control over terminals as a step that makes it harder for the enemy to use Starlink en masse in temporarily occupied territories and within hostile weapons systems. He emphasizes that from a security standpoint, inconveniences for some users are not a decisive argument when compared to the defensive benefits.

“Look, the state has taken a very strong and unpredictable step against the enemy. And if we compare the inconveniences for us with the losses and risks for the enemy — these inconveniences are bearable. This emergency shutdown helped prevent a wave of drones using Starlink terminals.” — Anton Sadykov

According to Sadykov, the enemy, in his view, is looking for ways to activate terminals on Ukrainian territory, including using intermediaries he calls “drops” — people willing to register terminals for a reward. At the same time, he states that a barrier has now been created for mass activation: one must physically visit a CNAP office, provide identification, and sometimes even show the equipment.

As the head of Adaptis emphasizes, if more than one terminal is registered “supposedly for home, a summer house, or a vehicle,” the procedure becomes even stricter — requiring the physical presentation of the equipment. He believes this limits the scale: even if some enemy activations are possible, they won’t reach the “hundreds of thousands.”

Sadykov also addresses the business aspect: according to him, the company has not experienced a drop in sales. At the same time, he notes new restrictions affecting terminal use on vehicles: if a Starlink is installed on a car, it must not exceed a speed of around 75 km/h while moving, or the terminal may temporarily lock until the speed decreases.

The conversation also touched on passenger transportation. Sadykov says that on Ukrzaliznytsia trains, including the Intercity service, different equipment is used — Starlink High Performance — and that the encapsulation for these terminals was done by Adaptis.

“All Intercity trains use different equipment — Starlink High Performance. Our company handled the encapsulation for these terminals — you can clearly see our logo on top.” — Anton Sadykov

As the head of Adaptis explains, the overall logic behind the state’s actions was to create an element of surprise, and in this context, unnecessary public explanations could be considered undesirable. He links the abrupt changes also to managerial factors — in particular, the change of leadership in the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine and the fact that the new minister, Mykhailo Fedorov, in his view, has a different understanding of technology and its impact on the battlefield.

At the same time, Sadykov acknowledges that in practice, users encounter procedural nuances. According to him, CNAP offices can operate unevenly: in some places there is a ticket system, in others a live queue, and sometimes the issuance of tickets and the movement of the queue depend on the administrator. He emphasizes that he sees bureaucratic and systemic issues in this, but does not consider them decisive compared to the security goal.

The interlocutor also mentions information waves from the enemy. According to Sadykov, at one point messages began circulating urging people to “immediately turn off Starlink” — claiming that Ukraine was allegedly reading the GPS coordinates of terminals in occupied territories. He frames this as part of the enemy’s reaction to the rule changes and adds that he hopes for the effectiveness of Ukraine’s measures.

Why Starlink Is Hard to “Replace” and What About Other Satellite Systems?

Fedorov’s advisor Serhiy Beskrestnov (“Flash”) recently wrote that the Russians are switching to their own satellite systems, Yamal and Express. Sadykov asserts that currently no other satellite system can offer the Russians the same combination of capabilities as Starlink. He explains that this is due to its low orbit and lower communication latency, which is critical for tasks involving control and rapid data exchange.

“At present, no system can be compared to Starlink. Starlink is a low-orbit system. Conventional satellite systems operate at much higher altitudes, while Starlink is at about 500 km. This results in lower latency and faster data exchange. Controlling a drone via ‘regular satellite internet’ is extremely difficult,” Sadykov says.

According to the interlocutor, even if the enemy claims to be developing its own satellite systems, in practice it is difficult to compare them with Starlink in the near future, precisely because of orbital physics and the resulting latency. He emphasizes that for tasks such as drone control, a connection with minimal delay is required — one of the key advantages of the low-orbit approach.

In this context, Sadykov returns to the topic of “white lists” and speaks about the government’s motivation: in his view, the increased control was an urgent measure aimed at making it harder for the enemy to use Starlink in mass scenarios.

At the same time, as the head of Adaptis notes, the technical restrictions that appeared after the changes (particularly regarding use on vehicles) create new conditions for businesses and users. He emphasizes that these conditions have not stopped demand, but they must be taken into account when planning usage.

What Are the Advantages of Uncontrolled Circulation and Import, and What Is SpaceX’s Role?

Sadykov says that in the early stages, the lack of strict control over terminal circulation was, in his view, a plus: it helped quickly saturate the country with connectivity in case of blackouts and emergencies. But now, he says, the market needs regulation — so that supply is legal and transparent.

“Currently, you can officially buy a terminal only on starlink.com — and it may take two, three, or four months, no one knows exactly. It will cost around $600 (I won’t claim exact numbers), and you have to wait a long time. Or you can buy it on a marketplace: roughly $400, and you get it ‘today.’ The choice is obvious — people buy what’s available on marketplaces.” — Anton Sadykov, CEO of Adaptis

According to Sadykov, the shortage of an “official and fast” channel pushed people to buy on the open market. He also mentions the factor of price and tariffs: in his view, the tariff in Ukraine was $95, while in Europe it was €79; the difference, he says, is not huge but noticeable for Ukrainian households.

As the head of Adaptis explains, the government could, in his opinion, help make imports legal, while SpaceX could organize sales for large companies and retailers. He openly expresses Adaptis’ interest in becoming an official importer and emphasizes that Ukraine has enough specialists ready to sell openly, provide consultations, and assist with registrations.

Separately, Sadykov describes how in 2023–2024, SpaceX lacked Ukrainian-language support and instructions, making it difficult for users to figure out settings and reasons for disconnections on their own. He claims that part of this “field support” was effectively handled by importing and integrating companies, including Adaptis, although he still highly values SpaceX’s support system.

Production Capacity and Sanctions: What Are the Challenges for a Full Starlink Launch?

Discussing a potential large-scale rollout of sales in Ukraine, Sadykov asserts that production capacity should be sufficient — there are already several million terminals worldwide, and manufacturing operates on large-scale lines. He also mentions Starlink Mini as a practical and functional solution, which is scaled not “artificially” but industrially.

“American companies are very sensitive to compliance and sanction risks. In past years, there were complex legal discussions in the US around certain Ukrainian military units, which may have made large corporations cautious.” — Sadykov

As the head of Adaptis explains, he sees this as a possible reason for SpaceX’s caution regarding direct sales to Ukraine. He calls it a “conflict of interest” and emphasizes that Ukraine is Starlink’s largest market, but the market itself has both positive and problematic aspects.

Sadykov also mentions practices that existed in the market: some sellers bought promotional terminals in Europe and resold them in Ukraine “with debts.” He describes this as a separate layer of problems that reinforces the need for formalization and clear import rules.

In this context, he emphasizes that Adaptis now purchases terminals within Ukraine, since the critical stage for the company is the modification, protection, and adaptation for operating conditions — not the purchase itself. According to Sadykov, the focus is on physically protecting the terminal as a factor that “saves users’ lives” in combat conditions.

Blackouts and Direct-to-Cell: What Is the Advantage of the Ukrainian Experience?

Sadykov asserts that Ukraine has accumulated experience in using low-orbit communication on a scale that currently exists nowhere else. He stresses that it is precisely the war and energy crises that created conditions where both communication networks and infrastructure autonomy are tested.

“Ukraine is now a testing ground for the world. Here, not only weapons and innovations are tested, but also low-orbit communication technologies… We can have a situation where a large city like Kyiv is left without power, operator network batteries run out, and you realize: even in Podil, you can’t call anyone,” says Anton Sadykov.

According to Sadykov, other technologies are also developing in parallel: he mentions Kyivstar and the Direct-to-Cell technology as a way to have basic connectivity (SMS, and potentially more over time), but he emphasizes that it is incorrect to compare this with full Starlink service due to the different class of service.

As the head of Adaptis explains, a separate user segment is journalists. He recalls collaborating with Associated Press and journalist Felipe Dana. Together, they tested Starlink mounts and power supply using V-Mount batteries (commonly used in video production). Sadykov states that such setups worked not only in Ukraine but also in various countries — including Africa, Brazil, and Spain — during Associated Press work trips.

He adds that the company sees a civilian future — after the end of hostilities, according to him, the demand for connectivity “on the move” will not disappear — this includes trips to remote areas of the Carpathians, RV travel, and yachts. At the same time, he reiterates that Adaptis’ mission, for him, is to provide connectivity where it is needed most, including in crisis situations.

Separately, Sadykov mentions work on humanitarian missions outside Ukraine. In 2023, he worked in Turkey after the earthquake with World Central Kitchen and brought a test Starlink unit with him. He names specific locations — Hatay and Gaziantep — and describes situations where there was neither power nor connectivity, and infrastructure restoration “by the next day” was unrealistic.

What’s Next: LEO Competitors and Adaptis’ Plans

Speaking about the future, Sadykov emphasizes that Ukrainian teams have learned to quickly adapt technologies to real needs and extract an “here and now” effect. He also talks about the anticipated arrival of new players in the low-orbit segment and that the communication market is expected to become more competitive.

“We are awaiting the launch of Amazon LEO in the low-orbit internet segment: they were supposed to launch last year, but this year, it is expected they will appear (initially with a small number of satellites). We are waiting to adapt these solutions as well — this will change the market. The European Union is also building its secure system, and China is developing its own,” says Anton.

According to Sadykov, the arrival of new systems is seen by Adaptis as an opportunity for future adaptation to Ukrainian use cases — just as they have done with Starlink. He emphasizes that this is not only about military applications but also about civilian needs for autonomous connectivity.

A separate topic he highlights is the formalization of the market. The interlocutor states that he expects further steps from the government — particularly from the Ministry of Digital Transformation — so that the market becomes more transparent and companies can officially import, sell, and support users. He adds that Adaptis is already collaborating with the Ministry on certain issues and is ready to expand this interaction.

At the same time, the CEO of Adaptis returns to the principle that guided the project from the start: providing connectivity in situations where other channels are unavailable. According to him, this applies both to Ukraine’s war and blackout conditions and to international crisis scenarios, where connectivity is needed for coordinating rescue and humanitarian efforts.

Tags: connectivity weaponization empr.media interview Russian misuse satellite internet politics Starlink war tech Ukraine frontline innovation whitelist security

![Kyrylo Marsak in Olympic figure skating gear smiling on the ice at Milan-Cortina 2026, capturing pride, viral hopak atmosphere, and Ukraine energy. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/kyrylo-480x270.png)

![Visitors at the “Thank You With All My Heart” Ukrainian exhibition at the Council of Europe, featuring the Great Amber Heart and powerful war art. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/heart-300x171.png)

![Ukrainian Roboneers and Latvian partners at the signing of a defence robotics and underwater technology cooperation memorandum. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/oboronka-300x168.png)