From the Student Maidan to the mass shootings on Instytutska Street, this investigation traces the role of Ukraine’s Berkut special forces, including the notorious “Black Company,” in brutally suppressing protests. Using batons, tear gas, firearms, and coordinated abductions, they attacked unarmed civilians, killing dozens and wounding many more. After evidence was destroyed and perpetrators fled, years of trials revealed the fates of those responsible. Some were sentenced in absentia to life or long prison terms, including Oleg Yanishevskyi, while others were acquitted or escaped to Russia, evading justice.

February 20, 2014 became a turning point in Ukrainian history, however pompous that may sound. On that day, police officers in central Kyiv, attempting to suppress the protests, shot dead 48 people and wounded another 90.

However, the authorities might as well have tried to put out the fire with gasoline. The monolithic majority of the Party of Regions and the communists in the Verkhovna Rada began to crack. Despite all attempts by Russia, parliament retained control over the country. And Viktor Yanukovych, who was supposed to head a separatist congress in Kharkiv, fled to Russia, where from time to time he gives press conferences claiming there was a “state coup.”

Along with Yanukovych, part of the Berkut unit also fled — in particular, the “Black Company,” responsible for the mass shootings on Instytutska Street. A separate text about how the fate of some of them unfolded can be read here. In this piece, UP has decided to remind readers where Berkut came from, what these special forces were known for, and how exactly they were used to counter the Revolution of Dignity.

Public order policing: batons, tear gas, beaten protesters

After gaining independence, Ukraine needed its own special police units to replace the Soviet OMON. Thus, in 1992, the Berkut special unit was created. From the outset, it was tasked with combating organized crime and was subordinated to regional departments for the fight against organized crime.

However, as sometimes happens, it turned out that Berkut duplicated the functions of another police special unit, Sokil. As a result, Berkut was later reassigned to the Public Security Departments, and the scope of the unit’s authority changed somewhat: from then on, its members were responsible for maintaining public order, policing mass events, and supporting police operations involving the use of force.

Behind these dry and seemingly official words often lay the suppression of protests, rallies, and demonstrations. And Ukraine’s football fan movement could tell dozens of stories about the work of Berkut officers at stadiums.

One particularly telling case was the beating of fans at the Olimpiyskiy Stadium in 2007 during a match between Dynamo and Shakhtar. At the time, 50 special police officers spent about 15 minutes “restoring order” in the Dynamo sector, where spectators had lit flares and smoke bombs. The result was 22 detained fans, including minors.

Another incident worth recalling is the beating of fans in Zhytomyr during a Dynamo–Polissya match. On that occasion, more than 100 supporters were beaten with batons by police officers.

Among other well-known operations, one can recall the shooting during protests by Crimean Tatars near Sudak in 1995, which left two people dead, as well as clashes at St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv the same year during the funeral of Patriarch Volodymyr.

In 1998, Berkut officers used batons and tear gas to disperse a miners’ protest in Luhansk on Independence Day.

Later came the beatings of participants in the “Ukraine Without Kuchma” protests, and the protection of Kuchma and his administration during the Orange Revolution.

Subsequently, Berkut was used to suppress those dissatisfied with Yanukovych’s regime: this included the dispersal of the Tax Maidan and the Language Maidan, the crackdown on participants in the Vradiivka march, and, more broadly, the routine beating of protesters.

The total strength of this special unit varied over the years from 4,000 to 6,000 personnel. They were stationed across different regions of Ukraine in companies and regiments. The Kyiv regiment, incidentally, was one of the largest: it had one transport company and five combat companies. Its members included not only riflemen and snipers, but also divers, demolition specialists, sappers, and armored personnel carrier drivers.

It is the Kyiv regiment that interests us here — more precisely, its special company, which played the leading role in the mass shootings on Instytutska Street on February 20, 2014. However, their actions against protesters began much earlier.

The Student Maidan and the abduction of people

November 30, 2013. Maidan Nezalezhnosti. Night. Sound equipment is being removed from Kyiv’s central square, and sporadic clashes with the police break out, but the situation appears relatively calm. The overall mood on the capital’s main square is rather pessimistic: the mass rallies of tens of thousands have dwindled to a few hundred people, who cluster near the Independence Monument. It seems that a few more days, and the protests will fade away.

However, some figures within Yanukovych’s government — and possibly Yanukovych himself — do not want to wait. Deputy Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council Volodymyr Sivkovych, together with the leadership of the police and the Kyiv authorities, plans to end everything that very night: Internal Troops and Berkut officers are brought to the Maidan. The latter number 180 people. Among them is Dmytro Sadovnyk with his subordinates from the special company of the Kyiv regiment. They line up along Instytutska Street and wait for orders.

At around 4:07 a.m., the commander of the Kyiv Berkut regiment, Serhii Kusiuk, gives the order to clear the square. Sadovnyk passes this order on to his subordinates from the special company. His officers, together with others, storm the Maidan, surround the protesters, and begin brutally beating them with their hands, feet, and batons.

Within 15 minutes, the special forces clear central Kyiv of several hundred protesters. But that is not enough for them: Berkut officers chase people along the surrounding streets. The result is more than 50 people beaten to varying degrees of severity. Among them is 19-year-old Ustym Holodniuk, who suffers abrasions all over his body. However, this does not stop him from continuing to take part in the protests.

The following day, December 1, according to various estimates, from several hundred thousand to one million people take to the streets in Kyiv to protest.

January 2014. The protests are gaining momentum. Maidan activists attempt to march toward the Verkhovna Rada, but on Hrushevskyi Street, near the Dynamo Stadium, they are blocked by Internal Troops, with Berkut standing behind them. Yanukovych’s authorities are still trying to strangle the protest — and come up with nothing better than assigning special police officers to back up the titushky.

On the morning of January 20, protester Serhii Zahvoskin was walking up Instytutska Street. He had spent the night on the Maidan and decided to take a walk toward Arsenalna metro station. At the intersection with Bankova Street, however, he was stopped by 20 athletes. As soon as they restrained him, the titushky called their supervisors, who in turn contacted Kusiuk, the commander of the Kyiv Berkut regiment. He dispatched a Volkswagen Transporter with fighters from Berkut’s special company. Eventually, the special forces twisted Zahvoskin’s arms and forced him into the van.

Meanwhile, three more protesters — Yukhym Dyshkant, Dmytro Moskalets, and Artur Kovalchuk — were walking from Arsenalna metro station toward the Park of Glory. Near the Salyut Hotel, they were spotted by about a dozen titushky. The men were seized and dragged deeper into the park. A call was made to Kusiuk, who sent a Transporter to pick up the Maidan activists. Inside the van were the same special-company Berkut officers mentioned above — along with Zahvoskin.

In effect, the protesters are being abducted: they cannot inform friends or family about where they are or what is happening to them. While the four Maidan activists are driven around Kyiv, the Berkut officers threaten them in every possible way, including with death. The protesters take the situation seriously — especially at the moments when the police aim their weapons at them.

Eventually, the van stops at the Desniansky District Police Department in Troyeshchyna. There, protocols are drawn up against the abducted protesters, accusing them of mass disturbances. There is no problem with the evidence: the Berkut special-company officers improvise on the spot, inventing how exactly the four detained individuals supposedly tried to overthrow the constitutional order with Yanukovych at its head.

Yanukovych’s “Peace Plan” and the mass shootings

February 18, 2014. The protests reach their peak. The Verkhovna Rada is set to vote on returning to the 2004 Constitution — that is, restoring a parliamentary-presidential republic. Maidan activists come to support the vote. However, Yanukovych is prepared: the government quarter is blocked by Internal Troops, and behind them, Berkut officers and titushky wait for their moment.

The protesters cannot get anywhere near the parliament. Around 11 a.m., Berkut is deployed, using, among other things, Russian “humanitarian aid”: flashbangs and tear gas grenades more powerful than the Ukrainian ones. Protesters are mercilessly beaten, and dozens are injured, including from the explosions of Russian grenades.

While the police are maiming people, one of the opposition leaders — Oleksandr Turchynov — meets with Yanukovych. Yanukovych shouts at him, threatens to have everyone shot, and generally warns that no one will get away unscathed. Turchynov proposes a compromise: the Maidan activists return to Kyiv’s central square, and Berkut stops shooting and killing people. Yanukovych sits back in his chair and eventually agrees.

Meanwhile, the commander of the Kyiv Berkut regiment, Serhii Kusiuk, is guarding the Verkhovna Rada. At 4:00 p.m., he gives Dmytro Sadovnyk the order to select trusted officers, arm them with firearms, and head to the government quarter.

Around 6:00 p.m., Sadovnyk arrives at 152 Chervonozoryany Avenue (now Lobanovskoho), the base of the Kyiv Berkut regiment. He selects 26 fighters, who receive Fort-500 shotguns, AKMS rifles, PM and Fort-12 pistols, and live ammunition, and drive to the Verkhovna Rada. They wait. This is the “Black Company.” On February 19, they are redeployed to Instytutska Street, where they remain until February 20.

After the failed “anti-terrorist operation,” the police do not stop: the Maidan is not stormed yet, but protesters are showered with flashbangs and tear gas grenades, and blasted with water cannons. Protesters start firing back at the police, killing at least two — likely a group that includes Ivan Bubenchyk.

The police leadership decides to go all the way: Kusiuk receives orders to use weapons and passes them down to unit commanders. At 8:50 a.m., another commander of the Kyiv Berkut regiment, Oleg Yanishevskyi, coordinates the police retreat from the Maidan. Among others are special forces officers from Crimea. Unarmed protesters follow them — and gunfire is opened on them.

The “Black Company” advances toward the October Palace, firing assault rifles and Fort pistols into the crowd. By 9:15 a.m., the special-company fighters of Kyiv Berkut reach the observation platform near the October Palace. At this moment, shots are fired at them, killing Mykola Symysiuk and wounding Roman Panchenko.

Sadovnyk then joins the “Black Company.” Together with their commander, they retreat back down Instytutska Street to the snow barricade. Meanwhile, the officers have no intention of stopping the shooting at the crowd. By 9:20 a.m., the “Black Company” had likely killed 26 people.

At 9:30 a.m., the Berkut officers take positions behind a concrete barricade near the Cabinet of Ministers club, from where they continue firing at Maidan protesters. Around 9:54 a.m., they fire in the direction of the Ukraine Hotel. Behind the concrete parapet of the Arkada Bank, Maidan activists try to evacuate their wounded.

In one of the evacuation groups, a young man in a blue helmet is Ustym Holodniuk. He is killed by a shot to the head. The next fatality is the youngest Maidan activist, Roman Huryk.

The gunfire only ceases around 5:00 p.m. By that time, 48 people had been killed on Instytutska Street.

Evidence, the liquidation of Berkut, and a long trial

On the afternoon of February 21, following the Verkhovna Rada’s decision, the assembled “Black Company” and its commanders return to their base on Chervonozoryany Avenue.

Kusiuk and Sadovnyk confiscate weapons from their subordinates: 24 AKMS rifles, 3 Fort-500 shotguns, 1 SVD, and 1 Fort-12 pistol. The weapons are then taken to an unknown location, dismantled, serial numbers filed off, and dumped near Zhuky Island on the Vita River. The entire process takes approximately three days.

At the same time, Kusiuk orders all official documentation to be collected in the hall of one of the buildings on Chervonozoryany Avenue. In total, nearly 250 different logs are gathered, containing information about the regiment’s weapons and fighters. The documents also disappear to an unknown location.

After Kusiuk and Sadovnyk destroy part of the evidence, it is time for the special forces to disappear as well: according to sources in law enforcement speaking to UP, they were taken directly from their base on Chervonozoryany Avenue first to Kryvyi Rih, and from there to Crimea, where the Russian occupation had already begun.

On February 25, 2014, Acting Minister of Internal Affairs Arsen Avakov signs an order to disband Berkut. That same year, Sadovnyk, as well as Pavlo Abroskin and Serhii Zinchenko, are detained on suspicion of involvement in the mass shootings.

However, in the fall of 2014, Judge Svitlana Volkova releases Sadovnyk under house arrest. The special-company commander takes the opportunity to flee to Crimea.

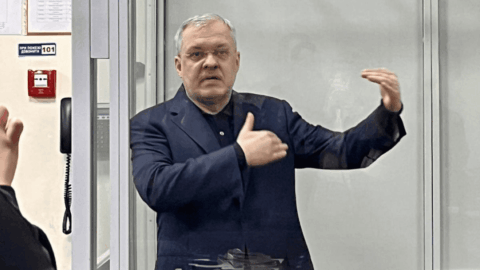

In 2015, three more former Berkut officers are detained: Oleg Yanishevskyi, Oleksandr Marynchenko, and Serhii Tamtura.

Five special forces officers were put on trial, accused of killing 48 protesters and wounding 90, and the case was approaching a verdict. However, the Russians intervened: they demanded that the Berkut officers be handed over to the territories they occupied, namely the so-called DPR and LPR. Otherwise, they threatened to block prisoner exchanges and refuse to release Ukrainians who had been held in these quasi-republics for years.

The Sviatoshyn District Court, which was hearing the case, refused to release the defendants. The Kyiv Court of Appeal stepped in: all the Berkut officers had their preventive measures changed, and on December 29 they were sent to occupied Donbas. Only two returned from there: Marynchenko and Tamtura.

After the start of the full-scale invasion, on October 18, 2023, the Sviatoshyn District Court announced the verdict for the shootings on Instytutska Street.

Yanishevskyi was sentenced to life imprisonment, while Zinchenko and Abroskin each received 15 years. All three were tried in absentia. Marynchenko was sentenced to 5 years but had already served this time in pre-trial detention, so he was released. Tamtura was acquitted on all charges, as the court found no evidence that he had fired at protesters or in any way contributed to their deaths or injuries.

Other Berkut officers from the assembled “Black Company” fled to Russia and obtained citizenship there. More about what happened to some of them can be read here.

![Flames and smoke billow from the Velikolukskaya oil depot in Russia’s Pskov region after Ukrainian SBU drone strikes hit fuel storage tanks. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/naftobaza-300x171.png)