Centrenergo’s agreement with the little‑known Teplosfera UA exposed a systemic corruption risk in Ukraine’s energy sector. After receiving a 132‑million‑hryvnia advance, the intermediary delivered only a fraction of the contracted coal and provided no real guarantees, despite the contract requiring payment after delivery.

A judge, reviewing the case, discovered that Teplosfera was a one‑employee company that purchased coal from state‑owned producers at the same price it sold to Centrenergo, leaving no commercial logic except extracting the advance. He issued a separate ruling, urging the government to regulate risky intermediary schemes and allow direct coal purchases by state energy companies.

In September 2024, Centrenergo signed an agreement with Teplosfera UA LLC. The company was supposed to supply 33.5 thousand tonnes of coal for the Trypillia and Zmiiv power plants for the heating season.

After receiving a 132-million-hryvnia advance payment, Teplosfera UA disrupted the schedule, delivered only 1.5 thousand tonnes, and did not return the remaining money. Centrenergo then went to court, where it turned out that the issue was much broader than simply dealing with an “unreliable supplier.”

The advance payment was not mandatory. The contract stipulated payment after delivery. Moreover, the company did not provide any real guarantees that could justify a prepayment.

Centrenergo explained the choice of a private company by claiming that state-owned producers allegedly had no coal available. But the judge discovered that Teplosfera UA had been purchasing this very coal from state-owned producers. The intermediary signed contracts with them only after the agreement with Centrenergo — and even after receiving part of the advance. In other words, there were neither safeguards for the money nor guarantees of receiving the coal at all.

The purchase price from the mines was equal to the selling price to Centrenergo. So the judge concluded that there was no commercial logic in this arrangement, and such a setup may indicate an intent to simply appropriate the advance.

The judge classified all this as a systemic deficiency in Centrenergo’s overall operations. Therefore, he issued a separate ruling addressed to the Cabinet of Ministers: to regulate procurement procedures in terms of risks associated with intermediaries and, in particular, to ensure the possibility for state-owned thermal power plants to buy state-produced coal directly, without any “middlemen.”

More details about this case and the Cabinet’s reaction are available in Bigus.Info video.

Lesia Ivanova: Energy — the “word of the year 2025” nomination hasn’t been announced yet, but judging by the events of just this month alone, I think that’s what it will be. On the one hand, we have the typical Ukrainian autumn panic season: intensified attacks on energy infrastructure, destruction of critical facilities, and as a result — scheduled outages and predictions of a total blackout, followed by a cold armageddon. For the fourth autumn in a row, it’s the same picture: some people get heated, others get irritated, others get scared. But this season — not in a good sense of the word — is still special. This year, probably for the first time, energy is driving Ukrainians mad not so much because of everything listed above, but because of corruption against the backdrop of everything listed above.

“They’re planning to keep building those f***ing protective structures, the numbers are insane.

ROKET — I’d wait. But, f***, to be honest, it’s a pity about the money, a pointless waste.”

Of course, I mean the large-scale corruption scheme at Energoatom that NABU and SAPO exposed two weeks ago. Operation “Midas” is multifaceted — it has many interesting plot twists and vivid characters. But, I remind you, at its core is a story about a brazen embezzlement scheme specifically in the energy sector. It would seem everything is already classic: procurement, kickbacks, money laundering, and then sailing off into the quiet harbor of Kozyn. But this story struck Ukrainians very painfully, primarily because it trampled on something that was already sore and extremely sensitive in the moment: when missiles are hitting you from the outside, and from the inside you’re being finished off with lines like “those f***ing protective structures we’re wasting money on.” And whom am I explaining this to — I think you and I have roughly the same spectrum of feelings here.

There was also a second reason — the involvement of top figures from the current government and people personally close to the president. I may be wrong, of course, but it seems to me that the public exploded in a way we haven’t seen since the times of Hladkovskyi. The combination of these two factors left the authorities no chance to “dodge” public anger by pretending nothing happened. Energoatom’s supervisory board was dissolved, the official Minister of Energy was dismissed, and the unofficial one as well. Audits were launched across all state companies, and in the energy sector overall they promised a full reboot.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy: The government has already begun auditing all state-owned companies, and the results of these inspections will be handed over to law-enforcement and anti-corruption agencies, and the government must provide them with full support. That is exactly what I am counting on.

Lesia Ivanova: All of that is good, all of that is right. But maybe it would be worth making some sort of list of priority, urgent ones? Something like a list of first-priority tasks that the president published on his channel: Energoatom — well, that one is obvious; Ukrhydroenergo — replacing the management; Naftogaz — a new supervisory board. We read this list and already felt that it was sorely missing one of the biggest energy enterprises in the country — Centrenergo. It’s somehow out of focus or something. Although if we are launching a chain of fast and radical decisions to put the energy sector in order, this structure definitely needs to be in the first ranks.

And today’s story is exactly about why. An interesting nuance: it — meaning the story — wasn’t uncovered by us, nor by our subscribers, and not even by law enforcement. It was uncovered already in court. Actually, not even that — it was uncovered by the judge. Yes, that happens too. He dug it up, and I suspect he was pretty shocked, so he just laid it all out in a separate ruling.

We, in turn, stumbling upon it in the court registry, immediately decided that we absolutely had to retell it: first, because it complements and expands everything that’s been pouring in over the last few weeks — were you already sick of hearing how the energy sector is being carved up? Well, get a bucket ready, because we’re about to add more.

And second — because we really want to draw attention to the problem while the government’s righteous reformist impulse is still alive and its desire to actually solve these problems is still hot.

So subscribe if you still haven’t, and let’s go.

In case anyone has forgotten or maybe didn’t know: Centrenergo is one of those companies that provides your home with electricity and heat. That is, it produces electricity all year round, and in winter it also warms your radiators. To do this, it has thermal power plants: the long-suffering Trypillia plant in Kyiv region, the Zmiiv plant in Kharkiv, and until recently, there was also Vuhlehirska. Well, “was” — it sort of still exists, but it’s in Donetsk region near Bakhmut, so it kind of exists, kind of doesn’t. So for the last three years, when we talk about Centrenergo, we really mean these two plants.

They run on coal, so ensuring its purchase and delivery is one of Centrenergo’s main tasks. In recent years, this task has been, let’s be honest, strategic — especially before the heating season. And last year, 2024, was no exception — if anything, the opposite. The entire energy sector was, pardon the pun, under high voltage from August, when Russia carried out, at that time, the most massive attack on critical infrastructure: ballistic strikes knocked out substations, and 4 million consumers had to be urgently disconnected. It became clear that Moscow’s seasonal escalation had started a bit early. So Ukrainians were already being asked to conserve energy during peak hours.

And in September — yes, in September — overnight, energy facilities in seven or eight regions were hit at the same time. The situation was tense, the risks high, the responsibility maximal. And at the end of September, Centrenergo went to buy coal. As I mentioned at the beginning, we learned this story from the court case, so everything I’m going to tell you next comes from there.

Actually, at first glance, the case itself seemed pretty simple. One of the suppliers Centrenergo contracted with was a company called Teplosfera UA. They were ordered to deliver over 30,000 tonnes of coal, which they were supposed to bring by the end of December 2024. For this contract, the company was even given an advance of 132 million hryvnias. But the supplier blew the deadlines, delivered only 1,500 tonnes, and… the final touch — didn’t return the money. So Centrenergo went to court: basically, here’s the situation — no coal, no money, let them return the rest of the advance. And the court was like: “Okay, fine, take the money from them.”

Stories like this are heard every day in commercial courts across the country — dozens, if not hundreds. And usually, it’s pretty straightforward: there’s a contract, a payment order, delivery acts, or no delivery — and then, in principle, all the judge has to do is correctly calculate the penalty or fine, and that’s it — the decision is ready. The decision in this case is more or less the same: dry facts, expected conclusion, calculation.

But besides the decision in the case, there’s a separate ruling that makes you look at this story in a completely different way.

First, it’s probably worth explaining what this separate ruling actually is. I think for those of you who aren’t lawyers, you’ve probably never even come across anything like it.

“ — And you came to court with this? You two? Are you out of your mind?

— Your Honor, with all due respect, but you can’t do that.

— I can’t, but you? You two can? With this, fake contracts, fake claims? Waste the court’s time on this? And my nerves?

— Your Honor, well, that’s kind of your job.

— Job? To legalize your whims? You think the court exists for that? I’m fed up!”

I imagine half of all court hearings involving state assets would look something like that if judges were allowed to say what they actually think about the case, its circumstances, and its participants. But they can’t: judicial ethics and all that. Although sometimes, I think, they must desperately want not just to talk — but to yell! And even throw the gavel at someone’s head. But — they can’t.

What they can do is write a dissenting opinion when a panel made the decision and you fundamentally disagree with the majority, or a separate ruling when you handled one case but uncovered something much bigger along the way. When instead of one violation several more crawl out. When you catch a prosecutor or a lawyer manipulating things, or catch a witness or expert lying. And ultimately, when you realize that the story that landed in your hands isn’t just some situational screw‑up, but the result of a major systemic failure in how state bodies or institutions operate. A failure that must be addressed, because otherwise the same problem will keep surfacing again and again.

In short, when someone has completely lost it or is fed up — that’s when a judge can, roughly speaking, open another tab in Word and, besides the case decision, write a separate ruling: share their discovery, complain a bit, and even “hand out some punishment.” Sometimes these rulings reveal a whole tragicomedy, more interesting and important than the case itself.

Our Centrenergo coal case turned out to be exactly that.

“Morning frosts and wet snow are a clear hint: winter is coming. Insulating yourself now, before the cold sets in, is the best option. And you can do it on the website or at the Ukrarmor flagship store. Ukrarmor is one of the largest stores of tactical clothing, footwear, and gear in Ukraine. They have everything you need: from thermal underwear to the warmest seventh-level field clothing for service. Thermal underwear, fleece, or a softshell jacket will keep you warm both at home and at the bus stop on the way to work. For military personnel who are constantly on the move in the field — digging, carrying, working — there’s the warm sixth level, which doesn’t make you sweat, and the seventh level for when it’s -20°C and you need to stay on post for hours without taking off your body armor. All levels correspond to the latest American cold-weather clothing system.

Online orders are processed as quickly as possible. And even if you place an order in the evening, the package will be shipped the same day. And, as usual, using the promo code Bihus, you’ll get a 10% discount on Ukrarmor products. There’s a link to their website in the video description — check it out and get ready for winter.”

Lesia Ivanova: First and foremost, Centrenergo was not obligated to pay an advance. The contract stipulated post-payment: deliver the coal, sign the delivery acts — and within a month, receive the money. A prepayment could have been made, but only on the condition of a guarantee from the supplier.

The company did indeed approach Centrenergo with a so-called guarantee letter, but it was not a bank guarantee. It was just a letter that, in fact, meant nothing and provided no security. In other words, Centrenergo simply took their word for it and handed over 132 million without any real protection.

Off-topic: do you remember why they’re trying to put Kudrytsky, the former head of another large state company, Ukrenergo, behind bars? He signed a contract with a company and also gave them an advance, but there was a bank guarantee. So when the company failed the contract — the money was simply returned through the bank.

In other words, insurance mechanisms against jerks and force majeure exist, they are simple and they work. But those who use them get prosecuted, while those who just hand out money left and right seem to get no attention at all. L — logic.

But let’s get back to Centrenergo. The second thing the judge noticed: this company is not a producer, just an intermediary. And third: this intermediary didn’t win any tender, because coal procurement before the heating season is strategic — and with the war going on, everything is already complicated.

Centrenergo was allowed to make life easier for themselves and skip tenders, just signing direct contracts with whoever they found and whoever they wanted.

And here, any reasonable person would ask: “So where did this company even come from, and why was it chosen?” I suspect the judge asked the same question. Because at some point, he poked his nose out of the case materials and went — no, not even to Google. Are you sitting? Take a seat. The judge went to study the company’s registration data, history, and financial statements on the OpenData bot and Clarity.

What did he find out? That the company was brand new — not even a year old when the contract was signed, that its charter capital was 15,000, and it had only one employee. And the cherry on top — it simply didn’t have the funds to pay off its debt to Centrenergo.

If he had also checked YouControl, he would have immediately found another interesting detail: the owner of Teplosfera is connected to another Centrenergo supplier, which also failed a contract, and because of that, another judge, possibly in the neighboring courtroom, was hearing a very similar case for another 240 million. But more on that later — let’s finish with this one first.

And what did this judge do? He went ahead and, in a separate ruling, demanded an explanation from Centrenergo: “What the hell were you thinking signing a contract with these guys? And they’re just intermediaries, so why are you even ordering from an intermediary instead of directly from the producer?” And at the same time, he asked the producers themselves who sold what to these intermediaries and at what price.

Wait, hold on — is that even allowed? A judge is supposed to consider the case based on the materials he’s been given. Why is he surfing the internet, demanding explanations?

Look, the court really doesn’t have the right to collect evidence on its own, but there’s an exception — in legal terms: when the judge has doubts about whether the parties are acting in good faith regarding their procedural rights or fulfilling their obligations to provide evidence.

In plain language — this is when the judge hears that someone isn’t telling the whole truth, or, excuse me, is just bullshitting, or is submitting some shady document, or basically came to court not for justice but just to mess with someone, or not to get a decision but for some fake paper to cover themselves in front of someone else.

Then the judge, to really figure out what nonsense is being served to him, can demand anything he considers necessary. Ours did. And here’s what he found.

Centrenergo claimed that it couldn’t buy coal from state-owned mining companies because their output had fallen, and whatever they did produce was already sold out. Basically — none available. So they had to turn to a private company. Okay, let’s assume that. But did that company even have any coal?

From the responses of the coal producers, it turned out that Teplosfera had contracts with two producers, including the state-owned ones that were supposedly “out of stock.” But those contracts were signed after the contract with Centrenergo, after the guarantee letter, and even after part of the advance had been paid. Great, right? But don’t worry — we’ll deliver the coal, we guarantee it.

And that wasn’t even all the discoveries.

It turned out that the price at which the company bought coal from the producers was exactly the same as the price it sold it to Centrenergo. They bought it for the same price they sold it for. What’s the point?

Well, if you actually want to run a business, there’s zero sense here. The only point is if you weren’t planning to do business at all, but just to drain money from the customer upfront — and then bail.

And just to be clear — this isn’t even my conclusion. This is a simplified version of what the judge actually wrote:

“The absence of any difference in the base price of coal in the supply contracts raises reasonable doubts about the intermediary’s genuine intention to fulfill its delivery obligations after receiving the advance payment, as it eliminates the commercial component of such intermediary activity and leaves no other conclusion than that the advance was received for the purpose of using it.”

And you know, it seems this struck the judge so much that he sat down and wrote out the whole story — about the completely obvious unreliability of the supplier, the bogus guarantee, and the totally unjustified risky prepayments (read: the sad ending of this story could basically have been predicted and even prevented, if anyone at Centrenergo had bothered to care).

By the way, the judge even devoted a separate paragraph to the idea that the wartime excuse — not bothering with open tenders, for example — does not relieve you of the obligation to do your job conscientiously: to buy efficiently, save money, and fight corruption.

Ultimately, the judge concludes that this problem isn’t local — it’s systemic, affecting the entire fuel and energy sector. And the core of it is that the system for such intermediary procurements is simply not regulated for risk. Which means what? It means it needs to be regulated.

And the judge assigns tasks for the Cabinet of Ministers.

Wait, can a judge even assign tasks to someone?

Imagine this — yes, they can. Because a separate ruling isn’t just for complaining. See a flaw in how something works — write a ruling for the responsible party: to fix it, and to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

And the judge wrote to the Cabinet: that they need to somehow eliminate the risks of working with intermediaries and regulate direct purchases of raw materials from state producers, and also — figure out who specifically screwed up at Centrenergo, and give them a good “kick in the pants.”

Although, as for that last part, I suspect the answer won’t take long to find.

Of course, Centrenergo, like any large enterprise, has its own security officers who check suppliers and contracts. But it’s like — it’s like the Vuhlehirsk TPP in occupied territory: just because you technically have it doesn’t mean it works. And even if it does work, it’s not guaranteed that it works for you.

In court, Centrenergo claimed that they had checked Teplosfera and found no risks.

Apparently, unlike the judge, they don’t know how to use OpenDataBot and Clarity. Maybe that’s why Centrenergo has more than just one problematic supplier.

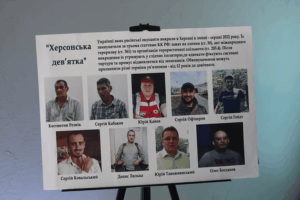

The owner of Teplosfera, which now owes Centrenergo 127 million hryvnias, is Ihor Kachmar. Little is known about him, but interestingly — he was also a co-owner of the company Energo Resurs Group. According to a court ruling, it still owes Centrenergo another quarter of a billion. That company did deliver coal, but of such poor quality that Centrenergo couldn’t accept it. And it also refuses to return the remaining advance.

There’s also a company called Optenergotorg, with a debt of 77 million hryvnias. It delivered less than half of what it promised, and, like Teplosfera, did not return the remaining advance.

We managed to get through to Kachmar with a simple question: why didn’t Teplosfera deliver the coal, and why aren’t they returning the money now?

He started explaining in a confusing way that, supposedly, the coal exists, they wanted to deliver it, but when they tried, Centrenergo wouldn’t accept it, and when Centrenergo did accept it — it wasn’t transported from here to there.

Honestly, I got the impression that Kachmar is mixing up different courts, but he ultimately refused to explain further.

Ihor Kachmar: And how am I supposed to return the money if it was already paid for the coal?

Lesia Ivanova: So where’s the coal then?

Ihor Kachmar: What coal? Well, miss… let’s just end this question here.

Lesia Ivanova: Yeah, it’s all quite confusing. But let’s be honest — that’s not even the point. That’s just the consequence.

The point is that, probably, the contracts shouldn’t have been signed, and hundreds of millions in advances shouldn’t have been handed out without proper working guarantees. Then we wouldn’t be running around now, trying to figure out: where’s the coal, and where’s the money.

So the problem is procedural. It needs to be addressed systematically — just as the court requested.

By the way, the court gave the Cabinet of Ministers one month to implement the ruling. That was in August. One month, as you can guess, has passed.

So we decided to check: what did they respond? What measures have they taken, or at least plan to take?

The answer came from the Ministry of Energy. If we summarize it briefly — they haven’t taken any, and don’t plan to. It seems the ministry somehow very creatively misread the ruling.

Think about it: what did the court ask for? To somehow regulate direct purchases from state producers. Not “limit” them, not “restrict” them, and certainly not “monopolize” them.

But for some reason, the ministry read it exactly that way and responded: “We can’t, we have a market.”

Ukraine is integrated into the EU energy space, where the main principle is free competition among energy suppliers. Imposing a requirement to purchase exclusively from a state producer could be considered a violation of competition law. Establishing, at the legislative level, a mandatory rule that energy-generating companies buy coal only from state enterprises is unacceptable due to the risks it poses to the stability of Ukraine’s energy system.

As for the second question — who specifically messed up at Centrenergo in the Teplosfera case — not a word. And, honestly, why would they?

And this is where it’s worth reminding two important points.

First: the chronicles of this absurdity and irresponsibility didn’t start yesterday — or even the day before. Corruption schemes and ineffective management of state assets are a historical legacy of Centrenergo, which the company proudly carries through the years.

NABU has investigated both coal procurement schemes in general and abuses by individual managers, which caused Centrenergo hundreds of millions of hryvnias in losses.

We’ve reported on how Kolomoiskyi’s management at one point extracted half a billion in just a few months from the company through a single scheme. And also on how, besides coal, there were schemes involving electricity — and gas too.

For many years, Centrenergo has ended up in nasty news headlines no less often than the same Energoatom. Yet somehow, none of this drew enough attention or concern to prompt radical decisions. And the same goes for this enterprise.

Second point — the supervisory board. Ten years ago, to fight anarchy in state enterprises, it was decided to introduce a management body called an independent supervisory board. The plan was that, under their independent oversight, enterprises would start operating more transparently and efficiently.

In short — more like a business, and less like a corruption feeding trough.

Ten years later, looking at what’s happening at Centrenergo, it seems that it hasn’t really helped much.

After all, all the mess we’ve been talking about today happened right under the nose of the supervisory board — a board that, among other things, approves major transactions of the enterprise.

On Centrenergo’s official website — where, sadly, the same kind of anarchy seems to thrive as in the company itself — we couldn’t find approval for the contract specifically with Teplosfera. In the reports for 2024, there’s a six-month gap.

But from documents for the previous months, we can see that the supervisory board approved transactions worth amounts dozens of times smaller than Teplosfera’s coal contract.

So this purchase, most likely, should have gone through their “OK.”

Since 2023, Centrenergo’s supervisory board has been chaired by Andriy Hota. He is considered a Yermak ally, as he was his advisor and headed the chief of staff office in the President’s Office.

Here’s a quote from Hota’s speech at the supervisory board meeting in September 2024:

“We are once again facing a serious challenge and have a critically important task ahead. Operational and effective decisions and actions are expected from us. It is important to ensure transparency in the process, of course taking security issues into account, and to maintain open dialogue among all parties involved. I have no doubt that we will live up to the trust of the Ukrainian people and the state leadership.”

This was literally just a few days after signing the agreement with Teplosfera.

And literally just a few days before they started transferring tens of millions to it — without, I remind you, any real guarantee of receiving coal or insurance in case the contract failed.

Well, that’s roughly how I imagine the category of “efficiency.”

Last week, as part of the promised overhaul of the energy sector, Prime Minister Yulia Svyrydenko promised not only audits but also the renewal of these very supervisory boards, including at Centrenergo.

On one hand, of course, that’s very encouraging.

But on the other — it’s incredibly frustrating that our government seems to only dare to make quick, radical decisions in the midst of yet another scandal.

Instead of calmly making them as part of a consistent, ongoing process.

I really want to believe, of course, that this isn’t just another quick swap of names instead of solving systemic problems. But I’m not one to make guesses, and under the current conditions, I’m even a little afraid to.

What I can say without fear is this: there is nothing more disgusting than destroying from within something that’s already barely surviving external attacks from enemy missiles and drones.

After the massive strike a few weeks ago, I think we were all struck by the cry from Centrenergo’s communications team — that post about “zero generation.”

I don’t know how much time, effort, and money it will take to restore it, but I do know that the company’s management style and approach to its assets must change immediately.

Otherwise, we will literally finish it off ourselves.

With that, I thank you for watching this video to the end.

Don’t forget the likes and comments, which help the video reach more people on YouTube.

And most importantly — please don’t hesitate to share it with your friends, because the more publicity there is, the higher the chances of solving the problem.

That’s what we’re working for.

See you next time.

Tags: Anti-Corruption Investigation Centrenergo Coal procurement scandal Embezzlement scheme Energy sector accountability Power grid mismanagement State-owned enterprise graft Ukraine energy corruption