Udav, a 55-year-old infantryman, spent 165 days in a cramped front-line dugout, enduring hunger, constant danger, and isolation, highlighting the human cost and harsh realities of prolonged frontline service.

Stories about 130, 165, or even 470 days that Ukrainian infantrymen spend in positions have drawn strong reactions on social media over the past few months. But they often lack context and explanations of how this became possible and how much longer it may continue. This was reported by Ukrainska Pravda.

These episodes are not as straightforward as they may seem at first glance. And they are far from isolated.

Alongside the enormous professionalism and heroism shown by soldiers in their 30s, 40s, and 50s who managed to fight and survive on the front line, there is a whole set of questions directed at commanders at all levels.

From why the Defense Forces lost control of the sky on their side of the front line, to how infantrymen can now be brought into and withdrawn from positions on that front line under conditions of a dense kill zone. How many kilometers will this kill zone expand to in 2026? And how is it even possible to fight under such conditions?

This publication is an attempt, by telling yet another story of a prolonged stay by an infantryman in positions, to raise these questions publicly.

The protagonist of our story is a 55-year-old infantryman of the 152nd Separate Jaeger Brigade with the call sign “Udav.” A volunteer, a husband, a father, and the grandfather of 12-year-old Iris, in civilian life he was a taxi driver with hand-to-hand combat skills.

Udav has spent nearly two years in the Defense Forces in Donetsk region. He fought near Katerynivka, Yelyzavetivka, Kurakhove, and Myrnohrad. He is currently holding the line in the Pokrovsk direction, near the villages of Udachne and Kotlyne. These are among the last settlements in Donetsk region before Dnipropetrovsk region.

One final fact about Udav: he spent half of last year in a tiny dugout at the zero line — from June 18 to November 30, 2025.

Forced Donorship

Among the places with the most unpredictable turn of events one can end up in within the Ukrainian army, newly formed brigades occupy a special position.

The 152nd Brigade, to which Udav was assigned in the spring of 2024 by the Solomianskyi District recruitment center in Kyiv, was exactly such a unit. It was one of the first newly formed brigades in the 150 series, deployed ostensibly to cover a long stretch of the front line and match the scale of the enemy’s army. And one of the first to be handed over for so-called “infantry donorship” to experienced units.

Immediately after its formation, the 152nd was “cut up” into battalions and companies and began to be attached to other brigades.

For senior command, this is a way to replenish an “old” brigade that is bleeding dry due to a lack of personnel. For an ordinary soldier of a newly formed brigade, it is an order to take on tasks that other brigades cannot or do not want to carry out with their “own” fighters. In Udav’s case, it meant going to observation posts where “their own” refuse to go.

In the army, this phenomenon is known as “fighting as attached forces.”

“We were the ones sent on all the unpopular tasks — that is, the attached units,” Udav says. “In the 79th, they promised us a guide to the positions, but we saw that they only had three groups of three people… and we understood that there was simply no one to lead us there. We had to learn everything ourselves. For us, it was wild, because we had come from a company of a hundred men.

“The second point,” Udav adds, “was pay. In assault and airborne brigades, everyone was on the ‘hundred’ (receiving a 100,000-hryvnia bonus — UP), while for us they counted every hour spent in positions to calculate the bonus. I only received the combat pay I had earned in 2024 in 2025. It was chaos. And there was no motivation among the guys to fight as attached units to other brigades — I think that’s when all these cases of unauthorized leave started.”

However, Udav himself had no need to go AWOL. If one can put it that way, he was extremely lucky.

All the brigades where he fought as an attached infantryman — the 79th Air Assault Brigade, the 5th Separate Heavy Mechanized Brigade, the 25th Air Assault Brigade, and the 37th Marine Brigade — despite a severe shortage of personnel, had a high level of planning and logistical support. The paratroopers and marines transported them to positions in Bradley vehicles. Over six months, Udav’s group had neither wounded nor killed.

Those who coped well with their tasks were later even actively recruited by the main brigades.

“But I decided to return to the 152nd — that happened in December 2024,” Udav recalls. “By then, they had stopped transferring us (to other brigades — UP), because, as I understand it, there was simply no one left to transfer, and everyone who remained returned to the brigade.

Thus, the 152nd Brigade, which began forming in the autumn of 2023, only started fighting as a full-fledged unit with its own subunits at the end of 2024. Udav met his “own” company commander, Sava, purely by chance only after six months of service, while on positions in Myrnohrad.

A year and a half ago, Udav would enter infantry positions for three to four days, less often for seven. Later, this increased to two weeks. By early 2025, the term had grown to a full month.

Udav explains this primarily by a shortage of infantry. To reiterate, the 152nd was allowed to fight with its own forces only when those forces were already at a minimum. Reinforcements in 2025, as in all line brigades, were insufficient.

In other words, the lack of infantry became the first reason for the longer periods infantrymen spent in positions.

The establishment of a kill zone became the second.

One Shot — One Corpse

The story of Udav’s six-month stay in a position began on June 18, 2025.

At the time, command promised all infantrymen a fully manageable and tolerable “deadline” for rotation out of positions — two weeks. Udav spoke with his company commander and the chief of staff, who cautiously mentioned a slightly longer period — about a month and a half. He himself mentally prepared for a maximum of two months, no more than 60 days.

“I think they didn’t lie to me,” the soldier reflects. “First, they couldn’t say more, because there would have been more refusals. Second, they were confident that 20, maybe 100 people would arrive to them from basic training. They didn’t know that those people would run away, refuse to serve, or turn out to be sick, because they had recruited everyone indiscriminately.”

From the point of departure to the required treeline — several kilometers — Udav and his partner moved quickly, in about two hours.

On site, they dug a 30-centimeter-deep foxhole — the minimum depth needed to be level with the ground — and then spent another two months expanding and reinforcing it. The excavated soil was carried away and scattered under bushes so that a pile of earth would not attract the attention of drones.

“I will remember the Donetsk soil for the rest of my life — it’s like concrete. You dig 30 centimeters, and after that the shovel and even the pickaxe just bounce off. It simply won’t dig. The guys used to say it’s cursed land,” Udav says flatly.

The only cover they could afford was branches, rain film, and camouflage netting.

Under the rules imposed by the kill zone, there are no dugouts reinforced with logs, no thick woolen blankets over the entrance to shield from the wind.

The reason is that even a well-camouflaged dugout is visible from a drone. Once detected, it is destroyed down to nothing by Russian drone drops.

At the same time, the Russians were “preventively” dropping KAB glide bombs on Ukrainian positions. Over those six months, between eight and twelve such bombs a day fell on Udav’s treeline (the weight of one KAB is roughly comparable to that of a Lanos car). After a neighboring position was destroyed, two more soldiers moved into the tiny dugout with Udav and his comrade. One of them was a combat medic; the other was an infantryman whose hand had been shattered by a mine.

“We thought he was going to lose the hand,” Udav recalls.

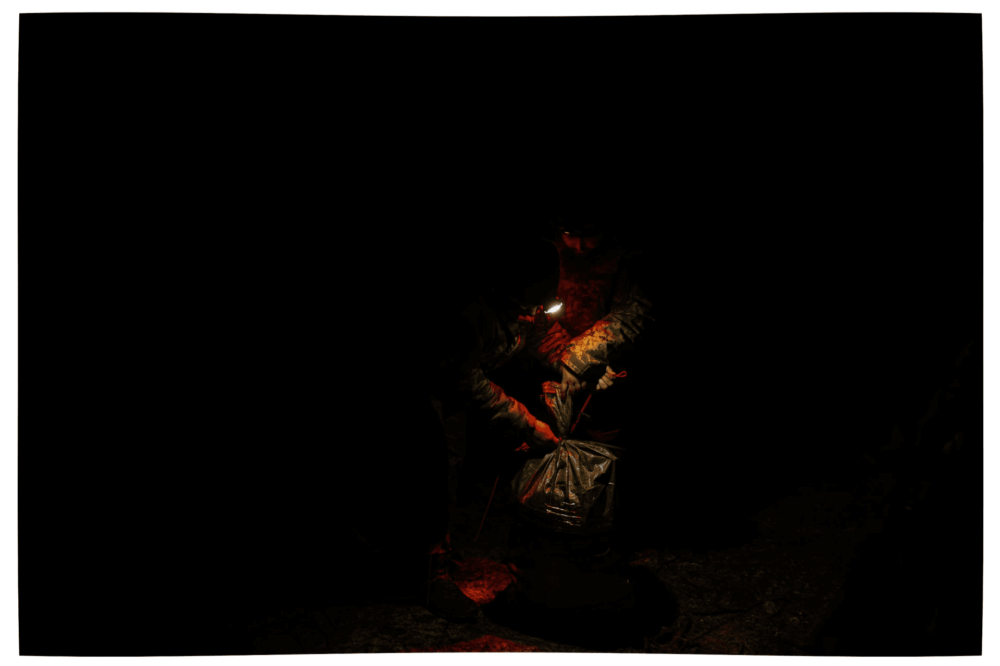

To survive in a kill zone, an infantryman has to be invisible.

Often this means not even leaving the dugout to use the toilet — relieving oneself into a bag. Spending months without straightening one’s back or legs. Not lighting trench candles to keep warm — let alone using a stove. At best, even in winter, “heating” is limited to heated insoles.

“I was at the command post, asking the commander: ‘Why are you sending people in there?’” Udav says. “He answers: ‘Because the defensive line has to be held there.’ I say: ‘And how are they supposed to sit it out there now, in the frozen ground?’ When I was coming out (at the end of November — UP), I was already wearing a warm field jacket, winter boots — they dropped them to me by drone — our feet were already freezing at night. Today snow has fallen, and I look at it and think: how are the guys supposed to be there now?”

Udav and his comrade lived at the position in a state of constant watch. During the day, they observed the front line together from their dugout; at night, they took turns, two hours each. At various times, the distance from their position to the enemy ranged from 30 to 70 meters — so close that they could not speak loudly inside the dugout.

Gunfire was a luxury they could not afford. The sound of a rifle firing — bang, bang, bang — carries for kilometers and would have completely given them away. So Udav kept repeating one rule to everyone: one shot — one corpse.

From infantrymen quietly observing the enemy, Udav and his comrade turned into an “anti-sabotage unit.” Their task was to detect and eliminate the Russians before the Russians detected them.

“How did we not go crazy? We watched each other,” Udav says. “We agreed that if we noticed changes in behavior, we would say so immediately. You might think you’re fine, but your partner tells you: ‘You were shouting at night that we were being surrounded and that we had to leave.’ We were very lucky that, together with that wounded man, a medic came to us. He was a huge help.”

Until August, it was possible to drop a sack of supplies onto Udav’s position every day. Canned food, rations, coffee, water, as well as gear, power banks, dry showers, and parcels from relatives — a total of 9–10 kilograms. That is the maximum weight a heavy bomber drone can carry.

With the onset of autumn 2025, the Russians began more actively targeting Ukrainian heavy bombers, making air supply increasingly difficult, and at times completely impossible. By the time of Udav’s rotation, nothing was reaching his position.

“Because of this, many panicked. The guys didn’t want to die a slow, humiliating death from hunger. When things got really bad, we would catch up to (Russian infantry — UP), kill them, and take their food,” Udav says calmly, as if describing something completely ordinary.

In his dreams, he saw himself walking through a supermarket with two carts: in one he put drinks — they were always desperately needed on the position — and in the other, pastries and fried potatoes.

Over six months, he lost 15 kilograms.

The Long-Awaited Fog

They had been trying to rotate Udav out since September 2025.

Command had sent at least five replacements, but none of them ever reached his position. Some were wounded and had to return. Others stopped at intermediate points, realized what awaited them ahead, and turned back.

“I would tell my wife over the radio: ‘Honey, I’ll be back in a week.’ And she would say: ‘You’ve been saying for 20 days that you’ll be back in a week!’ She wrote inquiries to the Ministry of Defense, to the President’s Office. She asked how I could go so long without a replacement. And the replies she got said I was at training. That irritated her,” Udav shares.

In the 152nd Brigade, they explain that in this situation, appeals to the president actually didn’t matter. No appeal in the world would have mattered.

Rotating people out of positions in the fall of 2025 had become practically impossible. The sky belonged to the Russians. The sky was theirs.

Under these conditions, the infantry’s last hope was the weather.

Commanders ordered Udav and the man with the shattered hand to wait for a dense fog and move under its cover — at that time, drones are practically blind.

Thick fog settled on November 28. The “road to freedom,” as the men jokingly called it, ran through the “gray zone” and took two full days.

“We went about three times the distance in the wrong direction. A little more, and we would have walked straight into the Russians’ lair. Over the radio, they were telling us: ‘Return to your position.’ But we were so determined to get out that we replied we wouldn’t turn back — we’d make one more attempt,” Udav sighs.

Thanks to bandages and the care of the combat medic, the man with the shattered hand kept three of his five fingers. He is undergoing treatment in a hospital.

The day after our conversation, Udav left for a well-deserved leave. After his return, the brigade plans to either transfer him to instructors or send him to training as a UAV operator.

For 12-Year-Old Iris, Who Does 60 Push-Ups on Her Fists

Udav spent 165 days at the positions.

During that time, Trump, in search of a “peace for Ukraine,” met with Putin for the first time in several years. The Ukrainian army cleared, and then lost control of, Pokrovsk again. At one point, unmanned systems temporarily stopped the Russian “Druzhba” oil pipeline. A Russian Kh-101 strategic cruise missile killed 31 people in Ternopil.

Udav knew none of this.

Not even about the clearing of Pokrovsk, just a few kilometers from where he was holding the line.

At one point, during an artillery lull, he and his partner even thought the war had ended. A ceasefire had come.

The realities of the front line during the kill zone were such that there was neither Starlink nor a “tapik” — a Soviet field telephone — at the position. The only way to communicate with the outside world was the radio. An infantryman might not receive a care package from home — usually food, like a chocolate cake or Olivier salad — but they would do everything possible to drop a powerful power bank. Only through the radio could he warn of approaching danger, including for himself.

“Losing the radio meant losing your life,” Udav emphasizes.

This is the infantryman’s second role in the current war — to be the eyes and ears of his unit. The first role will be described a little further below.

The only information that reached Udav over those six months came from commands from the headquarters: report the situation on the position, pick up a package, and so on. Plus, voice messages from his family. Thanks to the latter, he was able to endure it all in the first place.

Twice a week, Udav would dictate messages over the radio to his wife, daughter, and granddaughter — 12-year-old Iris — and then receive replies from them the same way.

“My granddaughter would say: ‘Grandpa, I love you, come to me.’ She trains in karate, has a fourth or fifth belt, does 60 push-ups on her fists, about 15 pull-ups — I haven’t seen anyone with that kind of fitness in any brigade! I thought: I will get through everything, endure everything, even hunger — just to come and hug her. To hug all of them. Everyone here is first and foremost fighting for their family — to keep the Russians away from them — and only then for their homeland,” Udav reflects.

Through those same messages, he learned that his mother — 89-year-old Mrs. Halyna — had, unfortunately, almost stopped walking. And near his home in Kyiv’s Solomianskyi district, several Shahed drones had fallen.

“Look at this,” he shows us a photo of a burned-out street on his phone. “This was the best school in Kyiv; Klitschko opened it. And this,” he scrolls further and stops at a white destroyed car, “this is my wife’s car. I told her: the main thing is that you’re alive. And I promised her an electric crossover.”

The guys didn’t believe it was Kyiv. “I told them that here (in the east — UP) it’s safer for us right now,” he adds.

The Infantryman’s First Task

Before saying goodbye, I cautiously ask Udav how justified he believes his prolonged stay in the position was.

I’m afraid that this question, coming from a civilian, might diminish both the brilliant work of holding an infantry position and the sacrifice of the strong man sitting across from me — a sacrifice I myself never dared to make. And yet I cannot help but ask it.

The thought keeps circling in my head: was there any sense in it? Was it worth sending him there at all?

Could he, having lost 15 kilograms and spent six months in a cramped dugout, have repelled a Russian assault?

To my surprise, Udav immediately replies that he has no doubts whatsoever that infantry is needed on the front line — no matter how hard it is, no matter how hard it was for him personally. The only thing that gives him pause is the length of time infantrymen are expected to remain on that front line.

“If we went into positions for shorter periods, our losses would be lower — about three times lower. When you stay in one place for that long, you can’t remain invisible to the enemy — and that’s the key thing for us. Enemy bodies are lying there — the Russians see them from drones. They understand that if one group disappears there, then another, it raises a question for them: why exactly there? If new people came in, they would dig new positions, in new places,” Udav explains.

Over a year of service, Udav seems to have learned well the first — logical from the command’s point of view and absolutely cynical in the context of war — task of an infantryman in this war. It sounds like this: to mark territory with your own presence. Like a post or a flag.

Machines cannot yet do this — nor can they react quickly to enemy movement.

Udav’s position west of Pokrovsk, near the villages of Udachne and Kotlyne, was set up at a point where Russian forces were infiltrating. Most of them were destroyed by drones; only a few out of a hundred, according to Udav, managed to get through deeper.

“Infiltration” became the word of 2025 before his very eyes.

Over six months, Udav and his comrade killed 14 Russians; two guys from a neighboring position, who later joined their dugout, killed 7; in total, all the soldiers at that rotation — 45.

After Russian forces executed Ukrainian soldiers on the Pokrovsk front, Udav made a personal decision not to take the enemy prisoner. Moreover, there was no place to hold them — the dugout was cramped, and it was impossible to leave the position and move a prisoner through minefields to the rear.

Heroic stories of war are often beautiful and rarely accidental.

Usually, they are the result of unresolved, accumulated problems that, for various reasons, ended up “well enough.” Behind them lie the stories of those soldiers who, after 130 or 165 days on positions, still haven’t been able to leave.

A huge level of professionalism in these people is layered over a dozen questions for commanders at all levels.

Tags: combat rotations EMPR.media frontline fatigue infantry positions interview analysis ukraine war war strategy

![Kyrylo Marsak in Olympic figure skating gear smiling on the ice at Milan-Cortina 2026, capturing pride, viral hopak atmosphere, and Ukraine energy. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/kyrylo-480x270.png)

![Visitors at the “Thank You With All My Heart” Ukrainian exhibition at the Council of Europe, featuring the Great Amber Heart and powerful war art. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/heart-300x171.png)

![Ukrainian Roboneers and Latvian partners at the signing of a defence robotics and underwater technology cooperation memorandum. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/oboronka-300x168.png)