The documentary Traces follows six Ukrainian women survivors of war-related sexual violence, capturing their testimonies, resilience, and post-traumatic growth, highlighting their

At the 76th Berlin International Film Festival, the documentary Traces by Alisa Kovalenko and Marysia Nikitiuk will premiere.

The film will be shown in the “Panorama” competition program, where winners are determined by audience votes (the film is also competing for the festival’s Best Documentary Award).

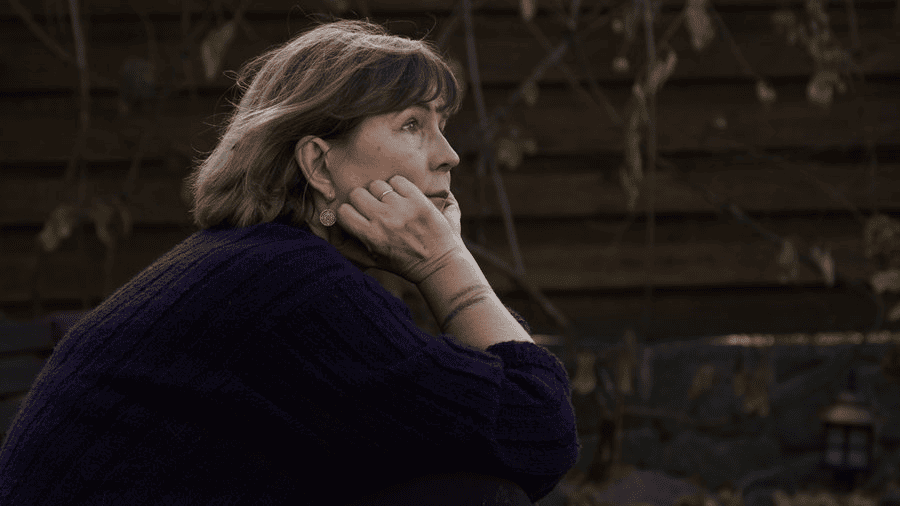

Traces observes the lives of six women, including Iryna Dovhan, founder of the organization SEMA Ukraine. This group unites Ukrainian women who have experienced violence during Russia’s aggression — in captivity or under occupation. The film explores the women’s experiences and the lasting marks left by the traumas of war.

Suspilne Kultura spoke with the directors about the balance between delicacy and anger, about healing and justice, and about how new practices are emerging in Ukraine for supporting those who have survived sexual violence during the war.

Alisa, tell us: what was the starting point of the film? When did you realize it would become a movie?

Alisa Kovalenko: It was a long journey. It all began with my captivity in 2014. For a long time, I spoke only about being held captive, but I didn’t talk about the violence — until I became part of the Theater of the Displaced. There, we experimented with new ways of processing reality, and I began speaking about my own captivity, thinking of making stories about other captives. Then Georg (Zheno — ed. note) asked me: “Why do you want to talk about others, and not about yourself?”

We met for a conversation: he was the first person I told everything to, and he suggested I simply write down everything I remembered. And indeed, I started recording my memories and transformed them into a play.

I didn’t fully understand at first why I needed this. Later, I realized that hearing about someone else’s experience could be important for others. After the premiere at the Zoloti Vorota Theater, the Helsinki Human Rights Union contacted me and invited me to give testimony. I did, and then asked if many women had already spoken out, and I was told that I was the first woman to speak about sexual violence in captivity. That was in 2016.

Before that, I had traveled to the front and made the film Alisa in the Land of War. In 2019, Iryna Dovhan reached out to me — at that time, the Mukwege Foundation decided to fund the first meeting of women who had experienced conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) in captivity. There were fifteen of us. We simply shared our experiences and talked about what we had gone through. It was something magical, because everyone felt a sense of sisterhood.

Later, we began thinking: what could we do together — as different people, of different ages, with different backgrounds. We started narrowing it down: what mattered was recognizing the problem, establishing the status of survivors, preserving memory, and breaking the silence. Then Iryna suggested making a documentary. It was in the air: a film that could become a tool to break the silence. We talked about it constantly, but I was very afraid and avoided these conversations.

When the full-scale war began, at a board meeting of our organization — which includes only women who have survived violence — Apolline from the Mukwege Foundation said there was an opportunity to get a grant to document crimes against humanity. We decided that a documentary film was probably the best tool for this. And I agreed to make it.

All the women promised they would support me at every stage, that I wouldn’t be alone. But, of course, at some point, I still found myself facing the material entirely on my own.

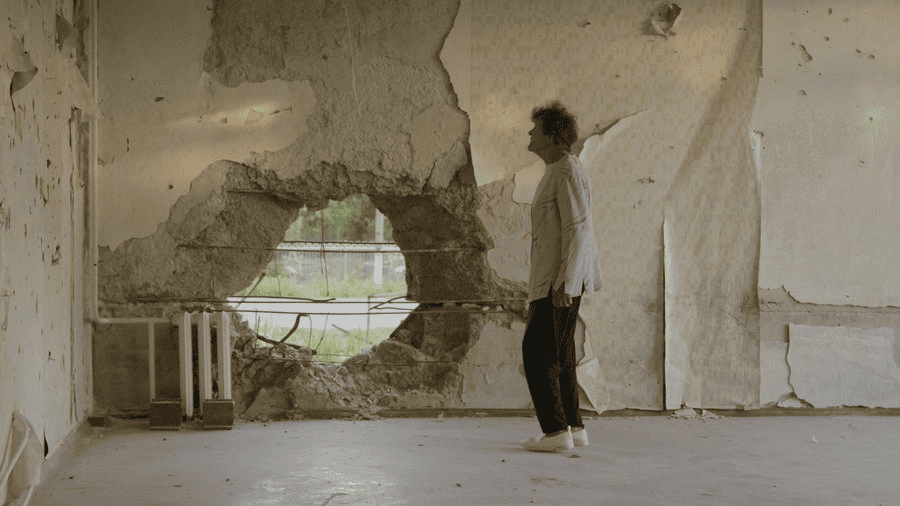

In 2022, I began traveling with Iryna to the liberated territories — starting with the Kyiv region — to document testimonies not only about conflict-related sexual violence, but also about other war crimes. Later, we went together to the Kherson region, where we recorded many stories that don’t appear in the film. There was one day when we documented five stories, and by the end of that day, I thought I wouldn’t survive it — I was lying in a hotel in Mykolaiv, realizing that I had a hole inside me. It’s impossible to endure so much pain.

When did these testimonies start coming together?

Alisa Kovalenko: At that point, I still didn’t know what form the film would take. What mattered to me were the testimonies themselves. I tried to compress each testimony into a story — not three hours long, but at least thirty minutes.

At some point, I had listened to so much that the horrors began appearing in my dreams — elements of their captivity mixed with my own captivity. Every night in my dreams, I was back in captivity. That’s when I realized I needed help and that someone should be invited to work with me on this material. I am also part of the community, and I document it, edit it myself, and sometimes present at conferences I film. I needed someone from outside.

Then we spent a lot of time talking with Marysia, and I thought this could be an interesting collaboration.

I didn’t know what visual form we would find, but from the start, I didn’t film “talking heads”; I simply spoke with the women. But what should we add visually? How would it all hold together? Even then, I was thinking: maybe it would be something about atmosphere, about nature, about the reality around us.

We slowly began searching for the form together and started editing. Later, Nikon Romanchenko joined us. It became easier for me; I no longer felt alone with this horror and pain. Although the first stage of editing was difficult for everyone. But you have to experience it to the point where it doesn’t traumatize you as much.

What were the stages of working on the film? You gathered testimonies, and then shot additional footage?

Alisa Kovalenko: I traveled to the Kherson region and filmed there. I was thinking about the form, and it seemed to me that it would be experimental. I already had some material beyond the testimonies — trees, leaves, the interiors of the women’s homes.

Together with Marysia and Nikon, we began combining the stories and editing. At the same time, I kept filming.

At one point, it became a classic observational film — about the community, its work and life, and how the women come together and support each other. I simply filmed the life of our organization.

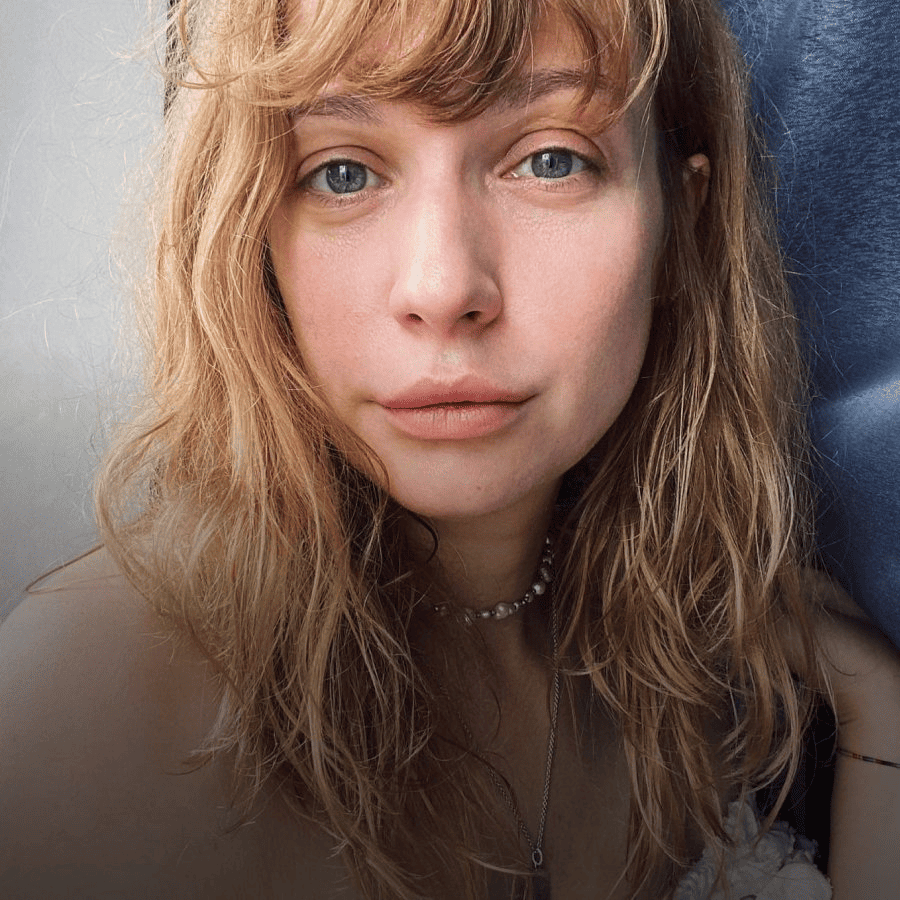

Marysia, tell us about the moment you joined the project and why. You and Alisa make an interesting and not-so-obvious tandem, since you create very different kinds of films. How did you come together?

Marysia Nikitiuk: At the start of the full-scale invasion, I was planning to mobilize, but I never did. Then I saw that Alisa had volunteered. I remember I started crying and began writing all sorts of silly messages to her. I didn’t find the courage to do it myself, but I saw that the person we are friends with and make films with had that courage.

In the summer of 2022, Alisa and I met in Sarajevo and began communicating closely. I wanted to be part of Alisa’s story and her courage, and when she suggested we work on this film together, I agreed. At the time, I was filming a project with teenagers from our joint initiative with Voices of Children.

Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) is one of my greatest fears. I haven’t experienced it myself, but it’s always in the background. I was very scared, but thanks to a shared connection with Alisa, her vulnerability, and my desire to measure up to what she is doing, I decided that this was an important topic and that I would step into it.

At first, we thought we might be able to find a fictional form for the testimonies, rather than a documentary one. We ruled out animation and reconstructions, but we were still searching for some kind of form. But when we started listening to the testimonies together — it made my insides churn.

Later, I had to distance myself from this material, because it required certain manipulations and structuring, but at first it completely overwhelmed me. Still, we came to the conclusion that nothing could be more powerful than this quiet and devastating reality.

At what stage did you decide that these particular women, together with Iryna, would be featured in the film?

Alisa Kovalenko: At first, we were documenting together with Iryna, and the women joined the process. From the beginning, we intended for this film to be our megaphone, an act of advocacy. So we talked a lot with the women themselves and asked who was willing to appear on camera, since not everyone would agree. Only those who were ready became the film’s protagonists.

At first, I thought Iryna would simply be connecting the women in this story, but then she essentially became the main character. This developed during the late stages of editing. We had a problem: the film felt like it contained two films — one about the testimonies and another observing the women coming together. We needed to balance this structure, and having Iryna as the central figure guiding us through all the events helped us achieve that.

In one interview, you said that far from everything you heard in the testimonies made it into the film. How did you select material for the final edit? Were there any red lines where you knew certain things wouldn’t appear, and why?

Alisa Kovalenko: With this subject, the most important thing is delicacy. I already have internal red lines when working with it; I understood that the most horrific details probably had to be softened, because no one could actually watch them. There are details in Halyna’s story that we decided not to include: she had bleeding, an infection, barely survived, drank some expired antibiotics she found in the house. At one point she says, “And I slowly went away.” I can’t imagine any audience member being able to endure seeing such things on screen.

Marysia Nikitiuk: I’ll be honest — I lack experience working with this topic delicately. When we started working on the film together, I had so much anger; I wanted to punish someone, to shock or even “kill” everyone with these testimonies. I insisted that we keep the details Alisa mentioned — saying, “Everyone should know.” But over time, we refined everything and left out particularly brutal details.

At some point, you have to work with these testimonies as material. You have to distance yourself; otherwise, nothing will come out of it. When we screened what I then considered a very balanced version at a professional event during Docudays UA, I realized we had found the right balance. We’re not showing this to Russians. We removed the harshest elements that could repel the very people we want to engage, not punish.

I also felt anger when watching this film, and I just wanted to shove it in people’s faces so they couldn’t look away.

Marysia Nikitiuk: What you’re saying — it makes me boil inside. But as directors, we know how things on screen affect people, and we have to be conscious of that.

Alisa Kovalenko: When we watched the rough cut at Docudays, Nils Pagh Andersen — one of the best editing directors from Denmark — was at the screening. He said he couldn’t breathe; any longer, and he would have had to leave the room. And this is someone who has worked with difficult topics in documentary film for many years. It was hard for him.

We’ve reached the point where we can’t spill all our blood. We need to convey something else. It seems to me that our film is about shifting the victim from an object to a subject position. These women didn’t just survive and endure this experience — they actively change the reality around them, becoming advocates for their rights, becoming leaders. For me, that is far more important in this film. Yes, there is evidence and testimony, but the most important thing is how these women are transforming, experiencing post-traumatic growth, as Iryna says.

These women are just titans, absolutely incredible. Did the idea of transforming the protagonists exist for you from the start?

Alisa Kovalenko: Life simply unfolded during the filmmaking process. The work on the film began very abruptly. There wasn’t a stage of development or research followed by filming. But I had already seen post-traumatic growth in other women who had previously joined our organization, and I understood that it would also happen with those we would meet in the Kherson region — that healing would take place.

As I became more involved in the lives of the protagonists, I saw in detail the changes they were going through. So, by the midpoint of the film, this arc became clear. But, of course, not in every detail, because each woman has her own path.

For example, with Nina, whose testimony is taken in the middle of the film, everything happened by chance. It was the first time she gave her testimony, the first time she shared her story, and I didn’t know if it would even make it into the film. I was simply documenting, focusing on her hands, because I wasn’t sure if Nina would be ready to reveal her face. Later, she went to rehabilitation, and afterward she came to our conference: in a summer dress, made up, smiling — it was incredible. When you see others healing, it heals and fills you too.

Marysia Nikitiuk: Life finds a way.

Our protagonists opened up to the camera also because they had gone through their own processes and supported each other. They spoke about what had happened to them very calmly. There was a sense of sisterhood, of a shoulder beside you. It’s a superpower, and it transforms. And although it sounds cliché, it’s truly about a vital energy that helps one survive this trauma.

Alisa Kovalenko: Dr. Denis Mukwege, a Congolese gynecologist who has helped thousands of women after the war in Congo, founded a movement that operates on the principle of leadership by those who have survived violence (a survivors-led movement). It’s about transforming survivors from objectified victims into active participants and agents of change. They get involved in negotiation processes and diplomatic missions.

Ukraine chaired PSVI (Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative) in 2025, and we passed the chairmanship to Congo. Survivors from other countries spoke there, and everyone emphasized this agency: that survivors are not merely recipients of aid, but it is crucial to involve them in active roles — they can be experts. This is a global trend.

It’s important to note that this has also led to men in Ukraine coming forward to testify more. Male organizations have emerged for those who survived conflict-related sexual violence in captivity — which is almost all of them. We work with these organizations and have created a coalition fighting to have Russia added to the UN shame list for CRSV. Russia is already on this list for deported children; we wanted to include sexual violence, and the UN issued a warning to Russia for the first time. This is an intermediate step. If the number of CRSV cases continues to rise, Russia will eventually be added to the list. We are resuming this advocacy campaign and will continue our work.

It’s important to understand that sexual violence in this war is not about gender — it’s about power. It’s about turning people into objects, breaking them so they can no longer be active in their society. It’s crucial that men also begin to testify.

We are shaping a new global practice. We launched a process of interim reparations — survivors tested this mechanism, improved it, made recommendations, and participated on the commission when people applied. In total, 1,080 survivors received these interim reparations. We are sharing our experience with Syria.

This is also a form of therapy — you do something to achieve justice and see the results.

Alisa Kovalenko: Yes. Restoring justice is one of the steps toward healing for survivors. Justice is a very slow process, and we don’t have a choice. But we already have cases where in absentia verdicts have been issued against Russian soldiers in CRSV lawsuits. That’s important.

How did the film’s title, Traces, come about?

Alisa Kovalenko: I immediately came to this title. At first, it was purely a working title.

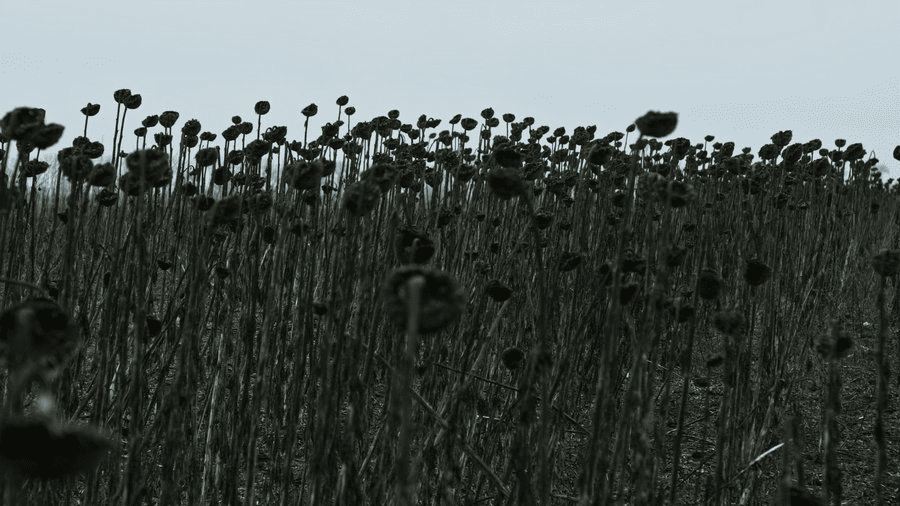

This crime doesn’t happen on its own. It comes with destruction. It’s not domestic violence; it’s conflict-related sexual violence in war. And I thought it was important to speak about the traces it leaves on different levels, in different dimensions. This trauma isn’t singular — it’s a layering of traces, the imprints of this war and aggression.

Marysia Nikitiuk: In my experience, this happens often: a film is born with its title. And it almost always stays. This one was so fitting that at first there was no need to look for an alternative. We worked with the image of traces throughout the entire film.

Alisa Kovalenko: Fields on fire — those are traces too.

Marysia Nikitiuk: Many artists work with the theme of traces, with fields scarred by craters from explosions, with what remains not only in people but in the land, in the houses. In the film, there’s a moment where Tanya moves her fingers over her shelled home. It’s a very symbolic scene. These traces will remain with us.

That’s why it’s so important now that we neither forget nor stay silent, so that post-traumatic transformation can happen for the whole society.

Alisa Kovalenko: When Tanya washes the wall after the Russians, she says: “We will wash away these traces, but they will never wash away theirs.”

Tags: Alisa Kovalenko Berlin International Film Festival Marysia Nikitiuk TRACES documentary Ukrainian film war cinema

![Ukrainian Roboneers and Latvian partners at the signing of a defence robotics and underwater technology cooperation memorandum. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/oboronka-480x270.png)

![Visitors at the “Thank You With All My Heart” Ukrainian exhibition at the Council of Europe, featuring the Great Amber Heart and powerful war art. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/heart-300x171.png)

![Ukrainian Roboneers and Latvian partners at the signing of a defence robotics and underwater technology cooperation memorandum. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/oboronka-300x168.png)