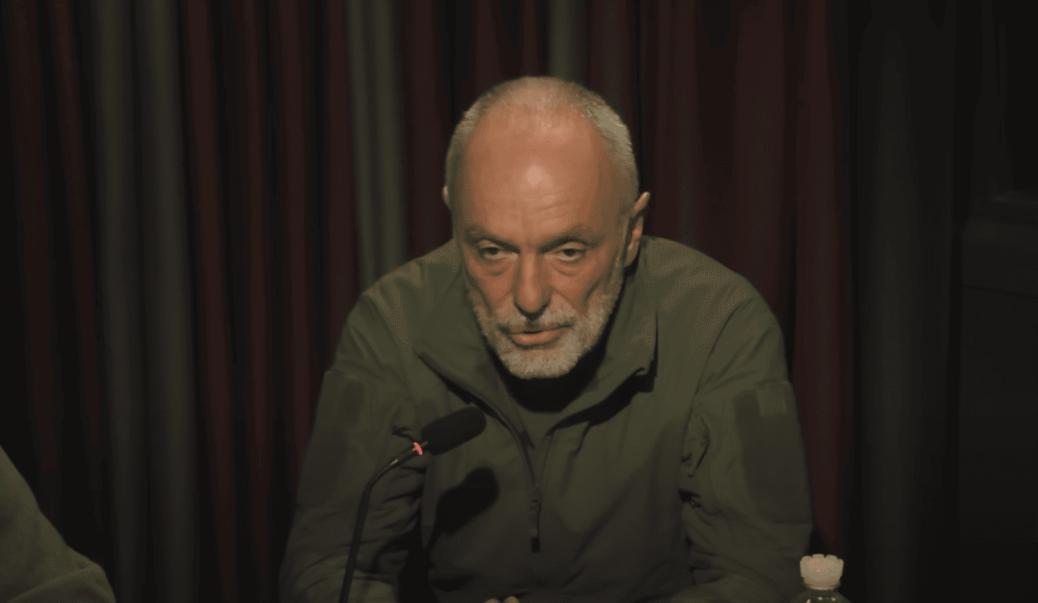

Yuriy Kasyanov, Major in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and his elite drone unit have been disbanded — a move he calls the result of “top-level corruption.” The team, known for successful deep-strike operations, including a drone attack on the Kremlin, operated advanced long-range UAVs developed in-house with volunteer funding.

According to Kasyanov, political pressure from the Office of the President and favoritism toward private companies like Fire Point undermined the unit, withheld resources, and threatened to scatter highly skilled operators. “This is a successful military team cut down by corruption,” Kasyanov says, highlighting the risk of losing expertise crucial to Ukraine’s defense.

In an exclusive interview on Radio NV Yuriy Kasyanov, a Major in the Armed Forces of Ukraine and an aerial reconnaissance specialist, Maksym Kasyanov, Lieutenant in the AFU and Valeriy Vasylyev, Lieutenant in the AFU reveal the destruction of their military unit, effective strikes against Russia, the scam involving Flamingo missiles and the manufacturer Fire Point, and communications with Yermak, Palisa, and Bezuhla.

Oleksiy Tarasov: A special broadcast is continuing on Radio NV. My name is Oleksiy Tarasov. Right now we have a very serious topic. We have three guests in our studio — I’m glad to introduce them: Yuriy Kasyanov, major of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, specialist in aerial reconnaissance; Maxym Kasyanov, lieutenant of the Armed Forces of Ukraine; and Valeriy Vasyliev, lieutenant of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. And now I’ll just introduce the topic: what happened. So, you, Mr. Yuriy, literally this morning wrote the following information — I’ll quote. You wrote: “Deyneko — this is Serhiy Deyneko, head of the border service, liquidated our unit on Yermak’s order. A successful military collective that carried out fantastic combat operations was cut down by top corruption. Details to follow.”

So, we gathered here to find out the details. First, if you can — tell us a bit about your unit: what kind of unit is it, what did you do? And my second question will be: how could it happen that it was liquidated?

Yuriy Kasyanov: Well, first of all, it’s not the Armed Forces as such, but the State Border Guard Service. But for us, as drone operators, it doesn’t make a big difference which structure it is. We actually started in another structure — we were volunteers at the start of the war, and now it so happened that we ended up in the State Border Guard Service, where we have been for one and a half years. Our unit — it’s, well, let’s say, like a regular company of RUBAK strike aviation complexes, but we operate at ranges, let’s say, from 50 up to 700–800 km. So this is middle strike, deep strike — these are long-range, very intelligent drones. We developed them ourselves since 2022 and used them ourselves.

It turned out that we are specialists in unmanned systems: we have worked with drones since 2014. And at the start of the war, when the war began, we took up arms, built drones — we had our own stock of drones, then other drones were needed too, and we started fighting like that, and we fought very successfully. The unit has very successful results. I’ll put it this way: confirmed successes are probably worth more than half a billion dollars. We haven’t lost a single fighter in this war — that’s also a great achievement for us. It’s the training of fighters, it’s the preparation of drones, it’s tactics and their employment, it’s RR stations, camouflage, and so on. So we did everything so that our unit wouldn’t lose a single fighter, so that we would carry out the combat mission.

We’re probably not very unique — but I’ll say, well, everyone does that. A huge part of our property is also so‑called volunteer property: things we bought with our own money, made with our own money, made with our own hands — vehicles, the unit’s permanent location, warehouses, workshops. We did all of that ourselves and received nothing from the state. Max will tell more in detail later.

For example, right now the unit is demanding that we quickly, quickly hand over the vehicles, but our vehicles are in repair, paid for with our funds, and we simply cannot physically hand them over now because they are in repair (parts of the vehicles). And I’ll say what happened: well, Mr. Yermak is very offended that I write about top corruption, about the company Fire Point, which — strangely — acquired a third of the drone market last year, while the year before last it didn’t exist at all. And this company is headed by people who previously had no connection to drones — a location manager, an architect of concrete furniture. And, oddly enough, these people are connected one way or another to the Office of the President: they sit on the council for enterprise under the President of Ukraine. Again, oddly, the president and the head of the Office travel to our dear partners in Denmark and ask the Danish government for money — huge sums — under the so‑called Danish model for this company.

We’re specialists in unmanned systems, so in my Facebook posts I wrote about how much their drone can cost and that they sell these drones to the state at, well, two–three times the price that’s acceptable. I also criticized the FirePoint rocket project — the Flamingo — because, you know, it’s impossible to design a rocket in nine months, as they claim: “we sketched it in a restaurant and built it in nine months.” Storm Shadow was developed over six years, Tomahawk over eight years; the Russian Kalibr that they attack us with — 12 years. So it’s simply impossible. And when they claim they bought thousands of AI‑25 engines, which haven’t been produced since 1981 — those engines simply don’t exist for these rockets. I won’t even start commenting on their claims that they’re going to build an engine factory. You understand, only five countries in the world have such factories — it’s a very complicated thing. To my mind, it’s a scam, and I said so outright.

And if there were to be consequences for this scam — because otherwise, you know, for Deyneko and our leadership there are no grounds to disband our unit. Really, there are absolutely no grounds. We, you know, are like a goldfish that carried out every order and didn’t require any investment in our unit — and delivered very good results.

One such result, which happened quite a while ago — in 2023 — I wrote about on Facebook: it was the attack on the Moscow Kremlin. Nobody was able to repeat our success. We had other operations too — unfortunately I can’t talk about them because they are classified, most of them, really. But really, I’d say we inflicted at least half a billion dollars’ worth of damage on the enemy.

Oleksiy Tarasov: I definitely remember that you were on our air then and commented on that operation when a Ukrainian drone actually reached the Kremlin. We saw that it exploded right next to their AquaFresh. Yes — unfortunately they weren’t able to bring it down then, but the effect was obvious. Look: there are Ukrainian developments that can do this — we can, we have the means to respond. But I have to ask this question: why are you sure that, in relation to what is happening to your unit now — specifically, to its disbandment — the Head of the Office of the President, Andriy Yermak, is directly involved?

Yuriy Kasyanov: Yes, I can answer. You know, this story started a year ago, a little over a year ago, when — on Independence Day — our president has a habit of announcing certain achievements to the nation and the world, and he then said that we have developed so‑called rocket‑drones. And, well, you know, now you don’t hear anything about them at all. First — yes. A journalist from Radio NV, Dmytro Tuzov, called me, and as a technical specialist I gave some answer about what those rocket‑drones might be. I said that such drones don’t exist in nature: if a drone has a rocket or jet engine, then it’s called a cruise missile or another type of missile. You could, say, call an anti‑aircraft missile a drone, because it has almost the same internals as a drone. And the Office of the President were very offended by my remarks, because they somehow decided that Kasyanov had insulted the president, exposed the president, that the president was lying, and that Kasyanov had unmasked him. There was an order — I have my own insiders — that Yermak instructed Syrskyi and Deyneko to look into this matter. Then Deyneko said, not to me personally but through another person, that the unit would be disbanded, liquidated. And generally, we ‘nursed a viper in our bosom.’

I then promised not to give any interviews so there wouldn’t be talk behind our backs. We hardly wrote anything on Facebook. But over the year the situation with our unit didn’t improve: people weren’t appointed to positions, weren’t awarded ranks, and what we’d been asking for since March — they didn’t give us money for components for the drones we assemble. In every possible way they tried to put obstacles in our way when it came to combat operations.

Oleksiy Tarasov: How did that happen? I mean, let’s talk a bit about this year, because really, if you say you have sources saying there was an order to, well, slow you down as much as possible…

Yuriy Kasyanov: You know, I’ll just add that Max and I met with Palisa — Yermak’s deputy — asking him to somehow sort this situation out. Palisa said that this couldn’t be true, that it was shameful, and he promised to help. The next day he called and said he was looking into the situation, and then he went into the fog. You know, our authorities have this habit of disappearing into the fog: you write to them, they don’t reply, they don’t pick up the phone — that’s it.

I also tried, through Maryana Bezuhla, to meet with her to try to resolve the situation. Again — no result, complete fog. And Deyneko also wouldn’t get in touch. Now, simply because I write a lot about FirePoint, I think their patience finally snapped, and they started acting in this way: disbanding our unit and generally getting rid of people — sending experienced UAV specialists off on postings to effectively destroy them. Because there’s also this trend, you know, of erasing people who are unwelcome to the leadership.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Why did you think Maryana Bezuhla could help you? Well — she was removed, right, from the national security committee, if I’m not mistaken. She herself left the Servant of the People faction. But really, many people link her to Andriy Borysovych Yermak. What was that conversation? We were just talking about Pavlo Palisa. And Maryana Bezuhla?

Yuriy Kasyanov: Well, you know, I’ve been trying to contact her for a long time, even about a year and a half ago when there were problems. Everyone has those problems with relocating people — to transfer someone from another unit to us — and she didn’t help with that issue, even though she left her phone number. You know, I probably posted on my Facebook page about recruiting people who were assembling our drones — I discussed that with her as well. And I just knew, again from insiders, that she’s connected with Andriy Yermak. I couldn’t get through to Andriy Yermak — I even went to the President’s Office to try to reach him, but I couldn’t get in anywhere. Maybe to reach the president, to, well, give us the opportunity to fight — we don’t need anything more.

Then I asked Maryana to meet so I could explain things to her. And there was another reason for the meeting: in March this year we had some really fantastic results, while in other units, well, good units, they didn’t achieve such results. We analyzed the situation, prepared a report with conclusions, and wanted to share it with other units so they could benefit from our experience. In the end, we did share it. I tried, through Maryana, to pass it to Andriy Yermak or someone from the Office of the President, the leadership, so they would give the order to distribute this document. But she didn’t do that either. Later, she wrote about me, claiming I was trying to get some perks from all this — like a transfer, a position, some nonsense.

Oleksiy Tarasov: I’ll return to the question I asked a bit earlier: what happened this year? What exactly did you observe happening to your unit? You said there was an order to put obstacles in your way — how did that work? Practically speaking.

Yuriy Kasyanov: Well, I think Max will explain more. I’ll just say, for example, that sometimes we receive a combat order with a hitch, because our DPSU service didn’t issue it to us; we get it through the General Staff, and then our own DPSU cancels it. That’s how it goes.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Max, so, what happened?

Maxym Kasyanov: The work of a military unit — that’s, of course, its primary purpose — is conducting combat operations. But aside from conducting combat of one type or another, there are everyday service issues as well, and there’s a lot of this: for example, appointing people to positions, supplying them with equipment (of course, to carry out combat tasks), ranks, and various incentives aimed at motivating personnel — to show who’s doing well, who worked better, and who others should look up to. In other words, there are a bunch of motivational levers within a military unit that a commander can use to steer his team toward victory.

When those instruments are withheld, a unit commander is heavily restricted in his ability to work. For example, in January we had meetings with very senior leadership in general’s epaulettes who said, “Okay, we’ve decided everything — we’ll officially appoint you to the post, everything as it should be: submit the names of who you want for promotions and we’ll appoint them.” Because for a proper hierarchy and chain of command in the army there needs to be a legal basis for those who give orders, so later they can’t say, “That wasn’t us,” or have their authority questioned by the people they lead.

Then, two weeks later, the same people act surprised and say, “What? Who? We promised to appoint them? You — who are you — want such a high position?” In short, this is sadly a corporate style of our leadership: constantly lying or making promises they never intend to keep.

For example, by the end of the month the commander has already sorted everything out — “by the end of the month you’ll have two pickups, a van, something else.” Because it’s impossible to carry out tasks otherwise: we drive our own vehicles — volunteer vehicles that were bought for us, donated to us, that we raised money for. For example, they don’t provide vehicles for operations. This year we received one vehicle, for instance.

And then — combat work. It’s the same: we sit — there are no combat orders. We say, “We have ready means of effect, we’ve already worked through target options.” Things we can effectively execute — let’s do something. “Wait, wait, wait.” Then the General Staff calls and says, “Guys, maybe you could go to work?” We answer, “Of course — we’re ready.” But we can’t give ourselves an order and just go. If you issue a combat order, we’re packed and ready to go at a moment’s notice. They issue that combat order; the combat order arrives — and within half a day another combat order from our leadership cancels it. And instead of executing a great, high‑impact target that would deliver real results — economic, political, and media-wise — there are many components in modern warfare: it’s not enough just to destroy a tank, you need to show it, so to speak, on video.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Of course, of course.

Maxym Kasyanov: It’s not enough just to reach, say, Samara and hit a tank there. If that tank is near Moscow — that would be, let’s say, a success, because it would immediately make a big impact. But otherwise, it wouldn’t. And instead of a great, high‑impact operation, which would obviously start from a better position, we’re sent to some random target — and the quote is like this: “Go, hit something, anywhere you want in this area.” I filmed video, sent our leadership the footage. Over this year, it would probably rank in the top three worst rains. It was simply impossible to get off the asphalt with a four‑wheel‑drive vehicle, because, well, the rain — you’d get stuck immediately. It rained heavily all day. Yuriy says: “The order is to work and not talk.”

Oleksiy Tarasov: Mr. Maxym, let’s take a literal pause here: we need a technical break, also for the news. After the news, we’ll return to this conversation. In our studio: Major Yuriy Kasyanov, Lieutenant Maxym Kasyanov, Lieutenant Valeriy Vasyliev. We’re discussing what’s happening with the unit. We’re talking about the news that it has been disbanded. This, of course, is a scandalous situation — we want to understand it better. After the news, in just a few minutes, we’ll continue the discussion.

This is a special broadcast on NV Radio. My name is Oleksiy Tarasov. We will continue discussing the scandal involving Yuriy Kasyanov’s unit. Just to remind you, I’ll quote: this morning Mr. Kasyanov posted on his social media: “Deyenko — the head of the State Border Guard Service — disbanded our unit on Yermak’s orders. A successful military team, which carried out fantastic combat operations, was cut down by top‑level corruption.” Yuriy Kasyanov — Major, UAV specialist; Maxym Kasyanov — Lieutenant; and Lieutenant Valeriy Vasyliev are in the studio with us.

So, Mr. Maxym, just before the news we were talking about what happened with the unit over the past year, when, according to your sources, an order came through to, well, maximize the slowing down of your unit. I understand the culmination was in the last weeks, the last months, when the threat arose that the unit might be completely disbanded. Am I understanding this correctly?

Maxym Kasyanov: Well, not exactly, let’s say, just the last month, especially. First — a remark: I don’t have any personal insider sources about anything being deliberately stopped — it’s just that everything points to it. You know, it’s like this: you might not know there’s going to be a wedding, but someone orders the flowers, someone buys the dress, someone orders the tart — and you understand that the wedding will happen. It’s the same here. No appointments, no ranks, no provision of intelligence for work, no vehicles — nothing. You understand that something is off.

In August, for example, due to the simply increased number of people in the unit, we decided to make some changes: increase the number of groups working, move some people to different positions for optimization. And a process that previously was resolved with a single report turned into a kind of ordeal overall. Because a certification commission appeared: people were sent to a psychologist, then to the military security service, their phones were taken, a colonel from military security came, shouting at people, sending them to polygraph tests. Overall, something very unserious was happening, and it lasted a month. Well, military security only recently.

Of course, such uncertainty affects people very badly: when it’s unclear what’s happening, why positions aren’t changing, why leadership doesn’t like us, and why we aren’t allowed to travel abroad, while the Armed Forces, National Guard — everyone else goes abroad on leave. You know, it’s like that. Everyone saw the video about Azov — and mine was in Italy. Why? Because going abroad is a kind of perk of military service: you defend your country, but during leave, you can go enjoy the birth of your child. For our serviceman, his child was born, and we had to fight to get permission to travel. Today it was canceled again, because now all our leaves and foreign trips are canceled. Only because of publicity was he able to do it last time. Let’s see if he can go to Poland to the maternity hospital now — we’ll see.

But one more thing I wanted to add: our leadership has this assessment that the unit is “ineffective.” Ask them “Why?” — well, we weren’t even given tasks: from our point of view there’s no way to show results. We prepared a report showing what the objective was, what the mission was, and what we achieved. They say, “Yes, that’s all very interesting, but was the objective hit?” I say, “Listen — we don’t have tactical nuclear weapons to use with our platforms and our combat load to strike reinforced concrete structures the size of, say, the Antonov aircraft plant building.” So no — “the target wasn’t destroyed in the classical sense,” they say, “so there’s no result.” I say, “Wait a minute, folks.”

You probably know about airport closures — a shutdown plan has been put into effect. People love it when aviation stops; it’s treated as a major headline. An hour of closing an airport costs the Russians at least $250,000. The Moscow aviation hub, for example, accounts for roughly two‑thirds of Russia’s air traffic; closing one airport for an hour is $250,000, closing five airports for an hour is already $1,250,000. And if the closure lasts longer, the losses grow accordingly. I say, “Look — the knock‑on losses from closing airports are significant for all those reasons.” And anyway, when I go around, people tell me, “Did you see the great results that were achieved somewhere yesterday?” — well, those are our results. But our leadership doesn’t care about that. They say about the airport‑closure results: “Remove that completely from the report. What is that about?”

Oleksiy Tarasov: By the way, it’s odd, because President Zelensky himself has highlighted this in several public statements — both in answers to questions and in his speeches. He said: “Look, when Russian airports don’t operate, we thereby reduce the economic capabilities of our enemy and reduce their ability to fund their war machine.”

Maxym Kasyanov: We closed them for more than 60 hours. If you multiply that out, it’s about $16.5 million. Not insignificant. Over the entire period of our service in the State Border Guard Service we expended weapons of effect of just over $2 million. That single line item has already caused many times that in damage. I won’t even list all the others… If you calculate within the DPSU, it comes to roughly $280 million. People say: “There was a target — you didn’t destroy it completely; in some places it was destroyed, but most targets are set.” So deep‑strike isn’t only about physically destroying, say, an oil refinery — it’s also about achieving certain political effects. Economic and political: close airports, create media attention to show “don’t get complacent — we can hit you,” show that we could strike, say, the president’s residence, or reach St. Petersburg. Maybe we didn’t destroy a key military object there and the enemy shot everything down with air defenses — but that will force the Russians to redeploy Pantsir and other air‑defense systems and invest in production, which creates many secondary losses and political dividends. A lot of missions are set for political purposes. And then, when the operation is analyzed by the military, they can always find a reason to say the task wasn’t completed, because the target wasn’t destroyed in the classical sense.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Listen, it’s clear to us that the decision regarding your unit is also political. It’s definitely not because your unit is ineffective. But alright, we are really waiting. For example, we reached out to Mr. Deyneko — we’d be glad to hear his comments on our air so he could explain why such a decision was made. But, it seems to me — again, just my subjective opinion — that the problem really lies in the fact that Mr. Yuriy Kasyanov, your father, is such an inconvenient person, someone with a strong character who can voice issues that people might not like.

Yuriy Kasyanov: I am inconvenient for any president.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Yes, I remember that you were also inconvenient under Petro Oleksiyovych Poroshenko. But listen — I need to return to what you wrote. You wrote that the unit was, as I’ll quote directly, “cut down by top‑level corruption.” Here I want to come back to Fire Point. We hear a lot about this company now. Indeed, we’re hearing very positive news that we may get our own long‑range missiles — they’re talking about the cruise missile Flamingo. We also recall that this company works on drones, and according to our sources — usually people who, unlike you, don’t speak about this publicly — they have questions about both effectiveness and price: for example, how much does one drone cost? What do you primarily see as the problems with Fire Point?

Yuriy Kasyanov: I see problems. The core issue is, first of all, the lobbying of one private company’s interests by our top leadership — directing our partners’ money solely to that company. That destroys the drone market. There’s no real competition. You see, if by order these drones are handed out to units, and units are required to only launch those drones so they can be written off on the basis of a launch rather than on the basis of a hit, you get a scheme: the more drones you launch and write off, the more you can later claim they were shot down by air defenses, jamming, whatever — and the money keeps flowing. The more of these drones you produce and have written off in units, the more profit you get.

I can say that I posted cost calculations on Facebook for the Fire Point FP1 drone because I could see which components and which engine it used — that’s not a huge secret. They claimed that at the start of last year the cost of their drone for the state was $55,000 — at least for the Danish government. But that’s the only source of funding right now. Our drone cost then, and costs now, roughly between $5,000 and $9,000. I’ll say our internals and components are no worse — and in many cases better — than that drone’s. The only real difference is that theirs is larger: a bigger airframe and a more expensive engine. But there can’t be such a huge gap in cost.

We’re accountable for our results: for a long time our strike success rate was above 70%. So out of every 100 drones we launched, about 70 reached the target and struck it. Now the success rate has fallen somewhat because the enemy has a lot more air defenses: they’re producing Pantsirs like pies and many missiles, so it’s much harder for everyone to get through. Still, our success rate is around 30%. From what I know, Fire Point’s success rate is on the order of 2–3%. You see, if you launch, say, 100 drones costing $55,000 each — and now they say they’re even more expensive — you’re spending on the order of $55 million for that launch. If only two drones actually get through, then you have to divide that $55 million by two, which makes the effective cost per successful drone $27.5 million.

Oleksiy Tarasov: So, if I understand correctly, your initial concerns about Fire Point and their drones came up because of their effectiveness.

Yuriy Kasyanov: Yes.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Got it. Now, people watching might just think, “So Kasyanov is making his own drones, he’s jealous of Fire Point. Look, they have orders, he doesn’t, so he’s speaking badly about them.”

Yuriy Kasyanov: I can answer that now. First of all, Kasyanov isn’t making drones for anyone. We only made them for our own unit. Since March, we haven’t received a single penny from the state — we earned everything with volunteer funds, I think about 15 guys, right? Drones. Not counting the fact that we made many drones for testing, built radio relay stations at our own expense, built vehicles at our own expense, did a lot of communication stations on our own. So don’t say that Kasyanov — me, Maxim, or Valera — sell drones to anyone or make money from this. We don’t produce like a company, Fire Point, 1,500 drones a month; we’ve always had very limited funding. God willing, we’d get money to make 100 drones in a month or two or three; then there’d be a six-month break, and we’d have to find volunteer funding again to make more drones. So there’s this, you know, Facebook mess: Yuriy Boyko, supposedly a journalist and lawyer, an investigator, attorney — I don’t know him, I’m not acquainted with him — who was basically set on us, dumping dirt on us (personally me, our team).

Oleksiy Tarasov: Who did he get the order from?

Yuriy Kasyanov: I think from Yermak. You see, he’s given information that no one should know: it’s very sensitive, classified information — the name of the unit, where it’s located, its structure, how many people are there, who commands the unit, who gives orders, where they get drones. Even the name of the company that made the drones gets revealed — I’m saying, it hasn’t been producing drones for a long time. But now we’re forced to evacuate people even from the buildings they were in because Yuriy Boyko disclosed a state secret during the war. It’s a state secret. I’ve already raised this unofficially.

Oleksiy Tarasov: I think it’s Volodymyr Boyko. Sorry — yes, yes, Yuriy Boyko — he’s different, from OPZZh; also quite a character.

Yuriy Kasyanov: Sorry. Yes, yes. But I didn’t see much difference between them. So, you see, I’m also publicly appealing to the SBU now: please deal with this issue. The person is simply putting others at risk: a missile or a “Shahed” could hit and kill people at various sites in Kyiv, outside Kyiv — we have many such sites — and he’s revealing all of this, writing complete nonsense. Saying that some military personnel “work for me,” or “Valeriy Vasilyev fines them 10,000 hryvnias” — you know, our salaries aren’t that high to fine someone 10,000 hryvnias; it’s completely absurd.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Well, he writes that the military worked for this company for free.

Yuriy Kasyanov: No, that never happened. And you can ask our soldiers: on the contrary, all the requests of the military were always fulfilled; everything was done so that the soldiers had everything — from toilet paper to drone reconnaissance stations, to testing various modifications. For example, when we made drones, there was one price; we needed satellite modems for the drones to have communication — we bought them ourselves, installed them on the drones, and carried out the work. Because our main task is the war and victory in this war. We are all volunteers: from the very first day, we went to the war in 2022, and actually Max and I have been at war since 2014. You know, this war is here with me; I would never skimp on anything to end this war. And to say that I am profiting from the war — you would have to be such a vile scoundrel, I can’t even express it; I was shaking when I read it. And this “verbal drain” from the President’s Office, I consider it just someone getting information — there’s no other way to get it; some comes from military units, some from the tax office, some from the treasury registers — you understand, a regular person cannot access these closed registers, yet he gets this information, and nothing happens: everything goes unpunished. So once again, I ask the Security Service to deal with this Volodymyr Boyko — I strongly ask.

Oleksiy Tarasov: You wrote in that long post that you’re ready to turn to NABU about a very interesting company. I understand you mean FirePoint? Do you actually have anything documentary that you can hand over to the National Anti‑Corruption Bureau?

Yuriy Kasyanov: Documentarily — no. But I know this company very well and what it does. I won’t say anything on air yet, until I submit the information, but this company is connected to Lieutenant‑General Deyneko, the head of the DPSU. So let NABU investigate. You know, it’s gotten unbearable: someone is making money while others are being cut down to silence them, and none of these people have anything to do with the war — it doesn’t concern them; they just get rich. And we, I mean Ukrainians, are supposed to fight and die so that these people grow wealthy, so they can build political plans and their hunger for power. I don’t know — it’s just a nightmare. I cannot remain calm about this.

Oleksiy Tarasov: I understand why you can’t be calm — obviously this situation is very, very unpleasant — that’s an understatement. But today you wrote that the unit has been liquidated. How was that communicated to you? What does it mean?

Yuriy Kasyanov: Let Maxym explain.

Maxym Kasyanov: It’s a very funny story.

Yuriy Kasyanov: The three of us were there.

Maxym Kasyanov: You know, recently it’s been kind of a pastime: they call me and say, “Tomorrow, report to the commander — prepare a list of details: how you can operate, we’ll sort everything out, it’ll be fine.” Then you go, and they call you: “Skip — everything’s cancelled; we’ll reschedule.” Then again: “Be there in three hours.” Okay, you go — and again it’s cancelled. It’s like a game. Yesterday, once again, they called and told us to arrive at 9 a.m. So we came. While we were waiting, we received information that made us think this could actually happen now. We went in, and the unit commander simply said, “Gentlemen, there’s a directive for organizational‑staff changes — here’s the number, dated yesterday.” So, basically, that was it.

Oleksiy Tarasov: That was today at 9 a.m.?

Maxim Kasyanov: Yes, yes, yes. And he even said, “You understand the reason — we won’t be announcing it here now,” but, well — thank you. We served with you, too. But even if we hadn’t served.

Oleksiy Tarasov: What happens next? What does this mean for — well, for all the servicemen in your unit: what will happen to them? What will happen to you? What will happen to us?

Maxym Kasyanov: First of all, we don’t yet know for sure. Right now we’re working to keep all our people together — those who came to us and believed in us — and to make sure they aren’t scattered. You know, there’s a little trick among commanders of different ranks: send the “undesirables” to the infantry. People who have never served in the infantry or been on the front — those who joined in 2014 and then became mostly staff officers — would be sent to the front. It’s a kind of pastime: sending everyone to different infantry units to disperse them. That rabble of undesirables — to break them up a bit. But we’re hoping we’ll fight for this and keep everyone. Where and in what structure — we don’t know yet; but I believe it won’t be here.

Yuriy Kasyanov: I’d like to add that these are highly skilled specialists — experts, top‑level specialists, programmers who volunteered to work with us because drones need programming. In civilian life they earned huge salaries — tens of thousands of dollars. And now they’ll just be sent to be beaten down, as they say — headfirst, you know? Or drone operators — these are all people trained specifically to work with our drones. These are unique, highly intelligent drones. Last year one assigned unit asked us: “Give us those drones.” We made 50 for them, ran training more than once, but they never mastered them and gave them back to us because they said they were too complicated. Yes, they’re very complex — but they’re also highly successful. I’d like Valeriy to tell more about our drones, if possible.

Oleksiy Tarasov: Yes, yes, please.

Valeriy Vasilyev: Well, first of all, some of the features we developed — for example, terrain following, not by mission but by altimeter. Right now, we’re working to push it into critical modes and actively follow the terrain. But, as far as I know, this is a rather complex task: even on other serial drones, they mostly fly by mission. But if you fly by mission and your GPS gets jammed, the altitudes set in the mission no longer work, because you’re not flying where you think you are.

Second, there’s intelligent behavior: when you’re being jammed by an enemy radar (REB), it’s very hard to spoof it because there are several levels of verification to determine whether the signal is real or fake. Unfortunately, we have to do this, because if we want to counter REB, the components can cost more than the aircraft itself. For example, CRPA antennas cost more than the drone, just for four elements, six elements — so we have to come up with software solutions to improve onboard efficiency.

Oleksiy Tarasov: I see. And I understand this intelligent product is not currently in demand. We can see the problem that arose. I promise that we will follow this situation in our broadcasts. I also want to address Mr. Deyneko, head of the State Border Guard Service: we would like to hear your comments on why this situation occurred. We will also reach out to other officials in this service. I thank you for this conversation. The situation is very unpleasant. Clearly, as experienced military professionals, you will find a solution. But as media, we are always open to communicating the problems you face. Thank you very much for this discussion.

I remind our audience: in the studio with us were Major Yuriy Kasyanov, an aerial reconnaissance specialist; Lieutenant Maxim Kasyanov; and Lieutenant Valeriy Vasilyev. I remind you that today Yuriy Kasyanov reported that his unit has been disbanded. In Yuriy’s view, this is a political decision, and possibly orchestrated by the head of the Office of the President, Andriy Yermak. Next, we will have the news segment. Again, thank you for this conversation. After the news, I will return to the broadcast.

![Volodymyr Kudrytskyi discusses energy missteps, shelters, and leadership decisions in Ukraine’s energy sector in a cold office interview.:contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/nardep-1-480x270.png)

![NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte at the Verkhovna Rada in Kyiv, announcing allied troops, warplanes and naval support will follow a peace agreement with Russia. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/marc.png)

![NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte at the Verkhovna Rada in Kyiv, announcing allied troops, warplanes and naval support will follow a peace agreement with Russia. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}](https://empr.media/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/marc-300x156.png)